Kevin Starr on history: ‘You don’t make up your world. You find it.’

- Share via

The agricultural development of the Imperial Valley should be dry as dust, but in Kevin Starr’s hands, it was a riveting tale of politics and personalities, environment and ambition and commerce, echoing so many themes of California as a whole. I remember exactly where I was when I read it: in my yard in Echo Park, sitting on the damp green grass.

That’s what the best writing does: It reaches out to freeze you, the place and the ideas in a moment in time. That Starr did this with histories, of all things, was nothing short of remarkable. He chronicled California’s past from its early days and the ugly colonial period up through the mid-20th century in a series of massive books that were transformative.

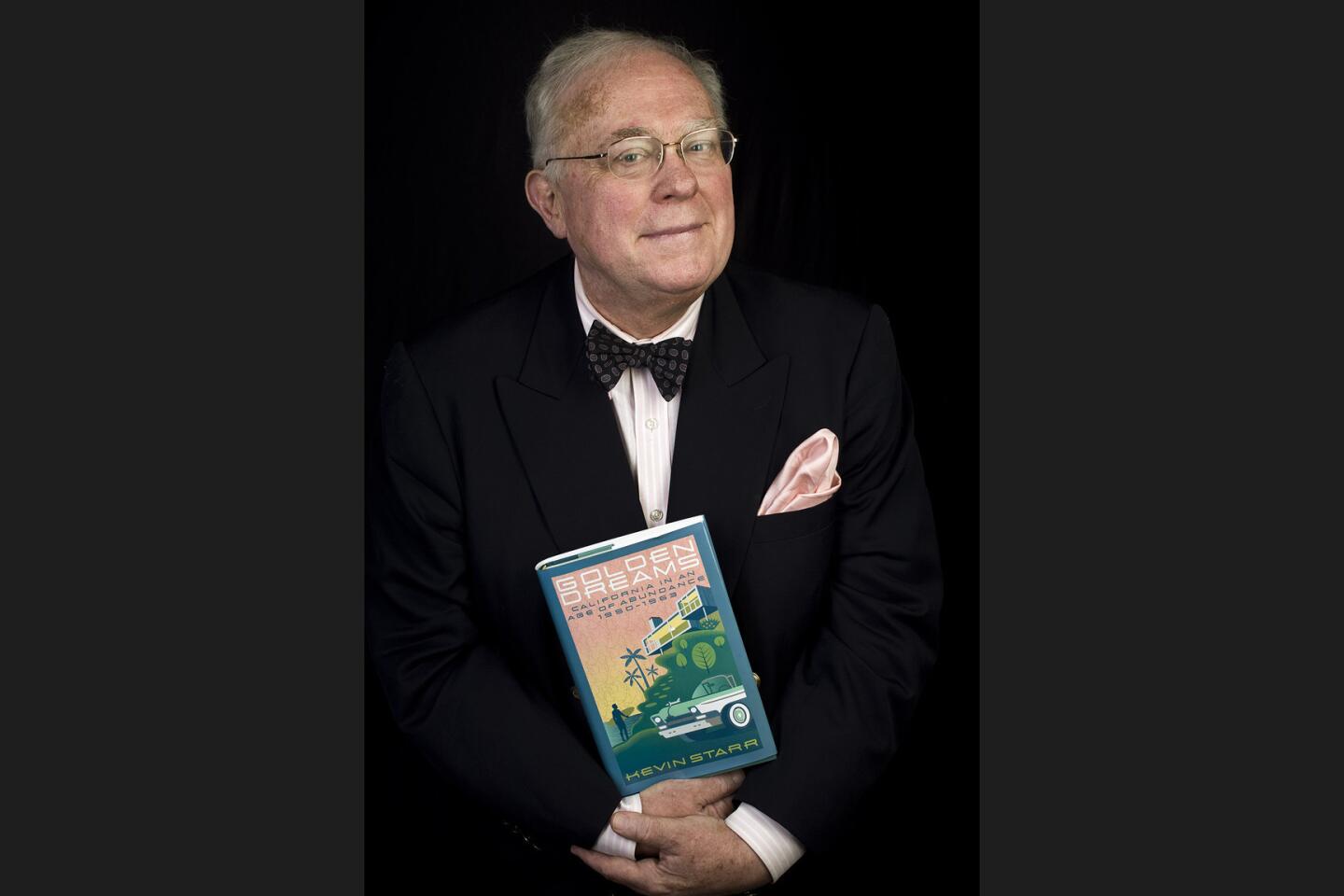

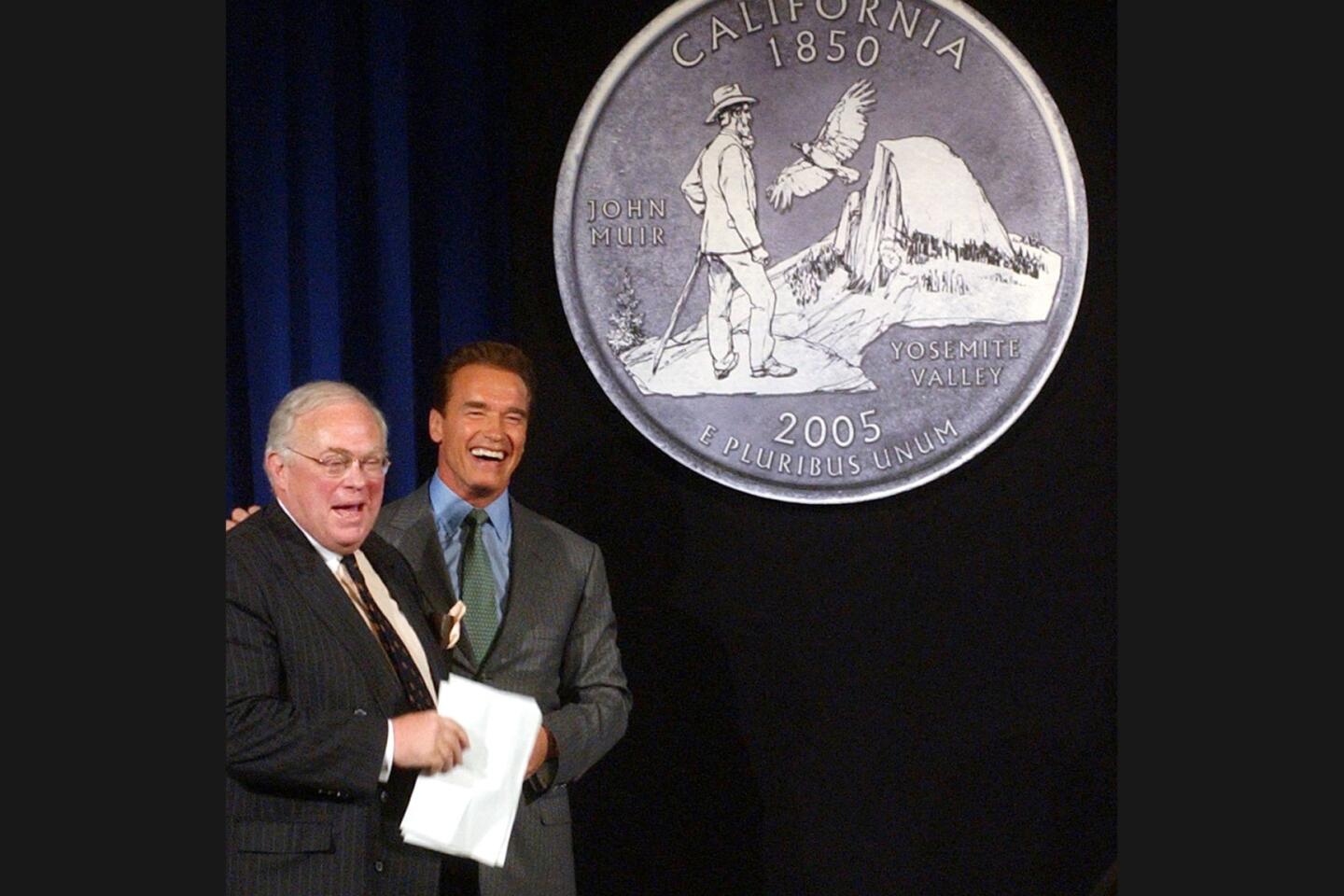

Starr, who died Saturday at age 76, was a public intellectual in a class of his own. He had been an avuncular, high-profile California state librarian. When you met him in person, it was as if the entire state library had come to life. A side benefit of any encounter with him was walking away with a new list of books to read. In conversation, he made electrifying connections that were possible only with decades of study and a brilliant mind.

This, of course, is exactly what he did in his books: make unexpected connections across a scope of centuries. As erudite as he was – he had a PhD from Harvard – he avoided the frippery of insecure intellectuals and instead wrote with great clarity. This, too, is remarkable.

Here are the titles of his main nonfiction series, which can be read in any order: “Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915,” “Inventing the Dream: California Through the Progressive Era,” “Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s,” “Endangered Dreams: The Great Depression in California,” “The Dream Endures: California Enters the 1940s,” “Embattled Dreams: California in War and Peace, 1940-1950,” “Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge,” “Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963.”

He also wrote for newspapers and magazines. When I interviewed him in 2013, the year he received the Robert Kirsch Award for Lifetime Achievement at the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes, he estimated that he had 1.5-million words in print in journalism alone.

“I write all the time; it’s my way of thinking,” he told me.

That dynamic mind drew together threads of the politics, industry, agriculture, religion, entertainment, fringe movements, power brokers and artists that brought California into being. In so doing, Starr redefined how we think about our history as Californians. We were not just a Gold Rush, earthquakes and a star-making machine. We were visionaries and scoundrels, ambitious and lost, successful and not, circling back to try again — a whole great mess of us making the state of California.

Starr’s secret project in telling the story of California in all its complexity was to tell the story of America. It’s here, his books tell us, that America comes into its full being. Forget the 13 colonies: The nation becomes itself in California. The California dream is the American dream.

Many of the people Starr wrote about in his California histories had come from somewhere else – for some it was the ultimate destination, for others, the end of the line. Starr himself was from here: a fourth-generation Californian, born and raised in San Francisco.

His circumstances were difficult: His father went blind, his mother had a nervous breakdown, and as a boy he went to live at a Catholic home. When his mother partially recovered, they lived in public housing. Starr was unhappy, effectively emancipating himself at age 12 or 13 with the help of his grandmother. He delivered newspapers, worked and saved.

He went to the then-Jesuit University of San Francisco, spent two years in the Army, and headed to the Ivy League. By that time, he had a deeply rooted perspective that California mattered (not a common notion in New England in 1965).

“I was trained at Harvard, my PhD was not in history but it was in American literature, American studies, American culture. So I sort of tend to see myself as a nonfiction writer who writes, among other things, about history,” Starr told me in 2013. “The imagination coalesces, sees patterns, coalesces narrative, looks for representative action, and is present, but you don’t make up your world. You find it.”

And now our world has lost Starr. At least we have his books.

ALSO

Starr in his own words: On urban renewal, water, fire, and L.A. vs. San Francisco

Making history: a 2009 interview with Starr

Dick Gautier, best known as ‘Get Smart’s’ Hymie the robot, dies at 85

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.