Hillary Clinton’s ‘What Happened’ says something revealing about America

- Share via

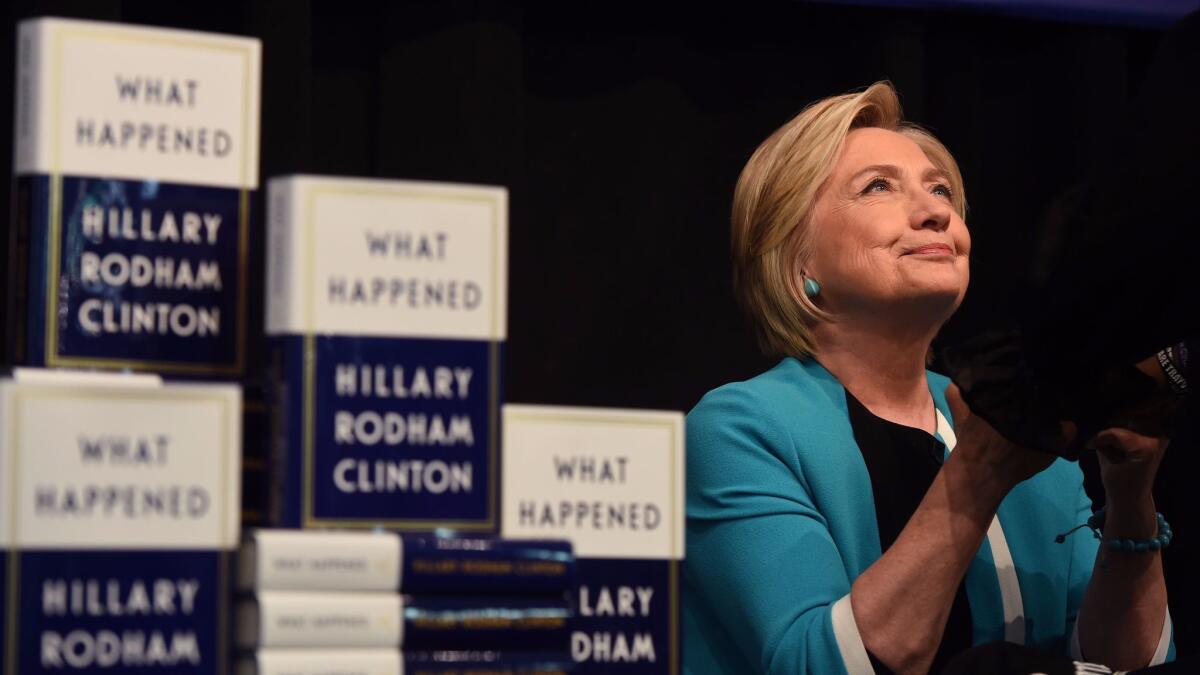

If you’re looking for a takeaway beyond the soundbites from Hillary Clinton’s 2016 election postmortem “What Happened,” you’ll have to read deep into the book. It doesn’t come until page 450, in a discussion of decorum and how it applies to losing candidates. “At first,” Clinton writes, “I had intended to keep relatively quiet. Former presidents and former nominees often try to keep a respectful distance from the front lines of politics, at least for a while. I have always admired how both George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush avoided criticizing Bill and Barack, and how Bill ended up working with George H.W. on tsunami relief in Asia and Katrina recovery on the Gulf Coast. … That’s how it’s supposed to work. But these weren’t ordinary times, and Trump wasn’t an ordinary president.”

Yes, yes, and again (for emphasis): yes. Clinton is correct. This suggests why “What Happened” is a necessary — if at times clunky and unconvincing — retrospective. Not because the former secretary of State lowers her guard (she doesn’t, really), nor because she has the right (of course she does) to tell her story in any way that she sees fit. No, the issue is the 2016 election and its aftermath, which, not unlike the tsunami or Katrina, has left us to reckon with a catastrophe of unprecedented scale.

I don’t want to re-litigate the presidential contest; it is over and our only option is, as Clinton observes in her final line here, to “Keep going.” But I also agree with George Santayana that “[t]hose who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” We disregard history at our peril; demagogues such as President Trump and Vladimir Putin depend on that. In that sense, perhaps, the most useful way to read “What Happened” is as one last instance of Clinton doing what she calls her civic duty. That the book is marked by her flaws (namedropping, contrived inspirational anecdotes, a refusal, or at least an inability, to reckon with her own failings as a candidate) as much as by her strengths (an expert’s understanding of policy and process, as well as an unexpectedly authentic sense of empathy) is only as it should be. This is her story, after all, and the most useful measure of it is to say the portrait that emerges is very much in line with the person, public or otherwise, we’ve known all along.

I had intended to keep relatively quiet. ... But these weren’t ordinary times, and Trump wasn’t an ordinary president.

— Hillary Clinton

Let me be honest: I voted for Clinton in both the primary (as a matter of strategy) and in the general (more enthusiastically). I’ve never cared all that much for her as a person, but her preparedness and level of achievement is beyond dispute. She should have been president, and she knows it; regret and loss is palpable throughout the book. And yet it’s also the case that she remains unable to reckon with just what happened in the 2016 election, looking for explanations, for reasons, while at the same time never quite uncovering her own complicity.

This is a tricky criticism, not least because it extends to all of us. Until returns started coming in on election night, did it really occur to anyone (even Trump) that she might lose? That’s what makes the election so difficult to reconcile — that and the starkness of the choice. It is perhaps unfair to expect that someone as close to the process as Clinton would be able to see it through a reflective lens. At the same time, she is relatively even-toned here, even when angry or fighting back.

Much has been made, say, of her criticism of Sen. Bernie Sanders, who contested the Democratic nomination and without question played a role in her defeat. At the same time, she is if not quite magnanimous then fair to Sanders, noting that while he and she disagreed on guns, for instance, “the Republicans were far more extreme” and giving him credit for helping to hammer out a progressive Democratic platform. Her ultimately conclusion, that wittingly or otherwise, “his attacks caused lasting damage, making it harder to unify progressives in the general election and paving the way for Trump’s ‘Crooked Hillary’ campaign,” seems incontrovertible and illustrates one of the key issues faced by her campaign: the extent to which voters and members of the media were predisposed to think the worst of her.

If ‘What Happened’ has anything to tell us, it’s that this is part of a larger problem with the culture and the way it deals with women.

In part, this has to do with oversaturation; Clinton was, perhaps, the most scrutinized presidential candidate of all time. In part, it has to with the appearance of indiscretion, going back to Whitewater and Arkansas. One of the holes in “What Happened” is its discussion of fake news, which Clinton largely identifies as a propaganda technique, promulgated in large measure by the Russians. While this is true, though, it is also the case that not only the right-wing outlets such as Fox and Breitbart but also mainstream media focused relentlessly on no-smoke, no-fire stories, such as Benghazi or Clinton’s emails.

Among the most trenchant sections of the book is one detailing Matt Lauer’s egregious performance at NBC’s “Commander in Chief Forum” on Sept. 7, 2016; Lauer repeatedly used the emails to question her judgment while giving Trump what amounted to a free pass. “Now,” Clinton confides, “I wish I had pushed back hard on his question. I should have said, ‘You know, Matt, I was the one in the Situation Room advising the President to go after Osama bin Laden. I was with Leon Panetta and David Petraeus urging stronger action sooner in Syria.”

Later, Clinton brings a similar wistfulness to her account of the second debate with Trump, at which he stalked her on stage, seeking to intimidate her. “Do you stay calm,” she asks, referring to her options, “keep smiling and carry on as if he weren’t repeatedly invading your space? … Or do you turn, look him in the eye, and say loudly and clearly, ‘Back up, you creep, get away from me, I know you love to intimidate women but you can’t intimidate me, so back up.’ ”

I would have loved to see her do the latter, but even now, Clinton isn’t sure. This highlights one of my problems with her as a politician: her reserve, her sense of caution, which is also, I would suggest, part of the reason she didn’t win. And yet, if “What Happened” has anything to tell us, it’s that this is part of a larger problem with the culture and the way it deals with women, and especially with successful women, who are generally regarded as a threat. When even someone as accomplished as Hillary Clinton is reluctant (afraid, even) to speak her mind about something we all witnessed — Trump hulking behind her on the debate stage, looming, getting too close — what does it say for the rest of us? Only that we are not as enlightened, as advanced, as we believe.

There are plenty of reasons for what happened in November, which also represented the manifestation of a seismic shift in presidential politics away from what is often derisively referred to as “business as usual” toward something more anarchic and unprepared. But at heart, I think, it’s a matter of our biases, racial and cultural and gender, all of which remain in force. “[W]hen a woman lands a political punch,” Clinton writes, “… it’s not read as the normal sparring that men do all the time in politics. It makes her a ‘nasty woman.’ ” Again, she is absolutely right. Read “What Happened,” then, not as score settling or revisionist history. Read it, rather, as what is it: self-serving in places but relatively honest, if not a knockout blow then something of a necessary punch.

Ulin is the author of “Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles.” A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

Hillary Rodham Clinton

Simon & Schuster: 512 pp., $30

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.