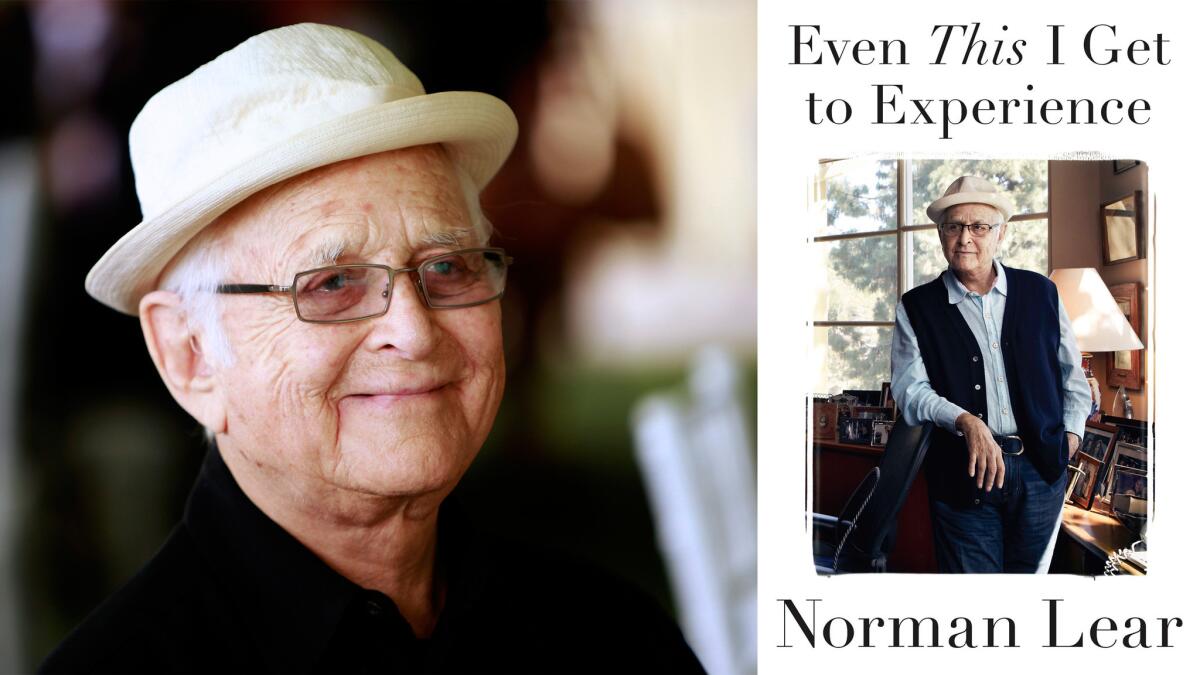

Review: Norman Lear’s memoir looks back at family and ‘Family’

- Share via

At 92, Norman Lear belongs to a world-tilting generation of writers that, these days, he has almost all to himself. Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks and not many others remain from the great westward migration of talent that began after Sept. 4, 1951, when the first transcontinental coaxial cable made it possible for Angelenos and New Yorkers to laugh at the same joke at the same time. (The Angelenos actually laughed a microsecond sooner; the New Yorkers waited to see if anybody else thought it was funny.)

Within months after the coaxial cable joined the coasts, “I Love Lucy” and Edward R. Murrow had made the jump from radio to TV. A writer for Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Norman Lear uprooted his family and jumped too, from his Manhattan apartment all the way to a Hollywood duplex owned by Buster Crabbe, the actor who’d played Tarzan and Flash Gordon. “All in the Family,” the show that would secure Lear’s place alongside Murrow and Lucy in the Television Hall of Fame’s freshman class, lay fully two decades in the future.

When Lear got to L.A., as we discover in his immensely likable new memoir, “Even This I Get to Experience,” he hadn’t let an already successful career as a comedy writer interfere with being a neurotic mess. He had a daughter he loved and a wife he barely knew. Punching out sketches for Martin & Lewis and Danny Thomas, he compulsively rewrote everything his partner drafted.

Lear’s insatiable professional drive and estrangement from his feelings were, inevitably, all in the family. He’d been born in New Haven, Conn., to an unappeasable Jewish mother and a charismatic con man, of whom he writes (wonderfully): “His office was his hat, and his desk was the band at its brim.”

For a while, H.K. Lear’s office was a prison cell — something it took his son half a lifetime to admit publicly. Given Lear’s fraught bond with his dad, it may be no coincidence that the most textured, tortured relationship on his best-remembered show focused on a son and his surrogate father. Archie and Edith Bunker may have loved each other from first episode to last, but it was Archie and son-in-law Mike’s halting nine-season courtship that made the show.

Thanks in part to Carroll O’Connor and Rob Reiner’s matchless playing, “All in the Family” got American generations arguing, and therefore talking. It hoisted a creaky, temporary rope bridge across a generation gap that threatened to swallow us — a gap looking no easier to cross now that Mike’s generation has switched sides.

To smuggle the show onto the CBS schedule and then keep it sharp required survival tactics that Lear acquired early: “Trying one tack after another to gain [my parents’] attention — occasionally to be listened to and, even more rarely, heard — I developed reasoning and presenting skills, along with a talent for herding ideas and selling them.”

“Herding ideas” encapsulates beautifully the dark arts of the television show runner, a job description Lear went a long way toward patenting. Around the “All in the Family” conference table, Lear fielded a murderers’ row of great writers, including Alan J. Levitt (“The Elevator Story”) and Phil Mishkin (“Mike and Gloria’s Wedding”) — sometimes credited in his memoir, sometimes shamefully not.

Lear’s eye for talent wasn’t limited to the writers’ room. He remembers junior agents hanging around his sets looking to sign up the slew of great unsung character actors Lear brought out — among them sonorous Roscoe Lee Browne, sly Gregory Sierra, those ubiquitous chameleons James Cromwell and Hector Elizondo, and sainted Bea Arthur, who wound up starring in the show’s arguably even better spinoff, “Maude.”

Lear had a good long run with “All in the Family,” “Maude,” “The Jeffersons” and a couple of critical darlings that didn’t last as long. But one key to longevity is, ironically, knowing when to quit. When the misses began to outnumber the hits, he had the good sense to concentrate on something new.

Gradually turning his attention to politics, Lear soon saw money in campaigns for the cancer it still is. He decided, rather than just bankroll Democratic candidates directly, to found the activist organization People for the American Way and reclaim the American flag from, as he saw it, bullies and absolutists.

For all his championship of the 1st Amendment and feminism, Lear’s no saint, nor does he pretend to be. One gathers he hasn’t been God’s gift to matrimony, either. And some of his ideas and locutions concerning women in his memoir are delightfully dated: “hot to trot,” for example.

Lear preens and blusters, but ultimately he’s more sinn’d against than sinning. He isn’t always a mensch in “Even This I Get to Experience” (italics, characteristically, his), but at least he can write like one.

Here’s Lear’s typically deft thumbnail self-portrait: “a nonagenarian in what the doctors tell me is excellent health, looking down at my arm and wondering, as I peck away on my computer, what my father’s hand is doing hanging out of my sleeve.” He never wanted a laugh track on “All in the Family,” and a line like that manages just fine without one.

In this city, Norman Lear and his post-coaxial contemporaries built a mass medium with their bare hands. On good days — as Lear well recalls, and recalls well — they made it sing. If only more with their talent had lived so long; if only more who live so long had his talent.

Kipen, founder of the Libros Schmibros Lending Library and author of “The Schreiber Theory,” is researching a project about the original generation of Southern California television writers called “The Portage West.” He teaches at UCLA.

Even This I Get to Experience

By Norman Lear

Penguin: 445 pp., $32.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.