Review: Mohsin Hamid’s ‘Exit West’ imagines a new way out for refugees

- Share via

In a world swarming with refugees, a world of travel bans, extreme vetting and giant walls, imagine mysterious black doors that transport defenseless refugees from war-torn cities to the safety of San Francisco and London. No overcrowded dinghies, no life vests, no Aylan Kurdis washing ashore.

Imagine living in a city in which “shootings and the odd car bombing” preamble a full-scale civil war, in which basic amenities to sustain human life are fast running out. Imagine a city pregnant with fear, panic, and terror, a city on the brink of collapse. And then imagine falling in love.

This is how Mohsin Hamid’s fourth novel, “Exit West,” begins.

For nearly two decades, Hamid has been successfully using the form of the novel to chronicle a particular epoch — Pakistani euphoria in the wake of nuclear tests in “Moth Smoke” (2000), consequences of post-9/11 Islamophobia in “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” (2007), and the recent economic ascendancy of Asia in “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia” (2013).

In “Exit West” he continues to document a particular moment in world history, but for the first time uses magic realism to explore one of the most pressing ethical and moral conundrums facing our contemporary society: how to address a refugee crisis.

In an unnamed city, Saeed, an adman, meets Nadia, an insurance agent, in a class on “corporate identity and product branding.” Saeed wears a beard but “not a full beard” and Nadia doesn’t venture outside without her black robes, not for devotional reasons but so that men will leave her alone.

As their love blossoms in subsequent months, the city is laid siege by militants. Those who have come to seek refuge in the unnamed city find the locals fleeing en masse. Everyone is looking for enigmatic black doors that function like wormholes to escape the collapse. A sense of urgency, and an edginess, runs through the narrative, heightened by Hamid’s crafted, minimalist prose.

“Saeed’s mother thought she saw a former student of hers firing with much determination and focus a machine gun mounted on the back of a pickup truck. She looked at him and he looked at her and he did not turn and shoot her, and so she suspected it was him,” Hamid writes. “She remembered the boy as shy, with a stutter and a quick mind for mathematics, a good boy, but she could not remember his name.”

When full-scale fighting begins, Saeed’s mother is killed along with countless others, and Nadia moves in with Saeed. They have not married and Saeed has politely declined Nadia’s offer of sexual intimacy. After one of their neighbors is butchered and his wife and daughters taken away by militants, Saeed’s father tells them to leave the city.

What is remarkable about Hamid’s narrative is that war is not, in fact, able to marginalize the “precious mundanity” of everyday life.

Following a tip from a friend, they meet with a man who “called himself an agent” to help them find a black door. Uncertain about the agent’s intentions, they pay him and he leads them to a black door inside a converted house. They enter the door and come out in a migrant camp in the Greek island of Mykonos.

They stay for a few weeks, but one night they are chased; they decide to leave the island. With the help of a girl who volunteers at a local clinic, they find another black door, which transports them to a big house in London shared by refugees from Nigeria, Somalia, Myanmar and Thailand. Saeed and Nadia find themselves in a comfortable room and decide to stay.

Over time Nigerian refugees become the dominant group not only inside the house but also in the neighborhood. While Nadia gets along just fine with the Nigerians, Saeed feels intimidated and threatened by them. He remains in the house only at Nadia’s insistence, and starts carrying a gun.

One doesn’t need to read “Exit West” in order to ask, Is it possible to think of a world free of xenophobia? Especially not lately, not even in the West. But here Hamid graphically explores a fundamental and important ontological question: Is it possible for us to conceive of ourselves at all, except in juxtaposition to an “other”? With a constant influx of refugees, “Exit West’s” London gets divided: dark London inhibited by refugees and light London inhibited by Brits. The locals are further divided: nativists “advocating wholesale slaughter” of refugees to “reclaim Britain for Britain” and “volunteers delivering food and medicine” to new arrivals.

Still unmarried, Saeed and Nadia fall out of love in London, and “to find a way out” (of the city, not of the relationship) they take another door — this time landing in a once-wealthy Marin County, in the San Francisco Bay Area, now populated mostly by migrants like themselves. They finally decide to part company, and each falls for someone new: Saeed for a preacher’s daughter and Nadia for a female cook. They do not meet again until they return to the city of their birth, a half a century later.

Apart from being an honest meditation on love and prejudice, “Exit West” is one of the pithiest and most powerful comments on the contemporary zeitgeist because it is deliberately noncommittal: Should Saeed and Nadia — and, by implication, their real-life analogs — exit to, or from, “West”?

Nicholson Baker has said that “[w]ars are bad for the novel, because suddenly all of our precious mundanity is justifiably marginalizable” because “[w]ars trivialize every small-scale concern you have, like saving newspapers or saving a train station. They call into question every minor joy.”

What is remarkable about Hamid’s narrative is that war is not, in fact, able to marginalize the “precious mundanity” of everyday life. Instead — and herein lies Hamid’s genius as a storyteller — the mundanity, the minor joys of life, like bringing flowers to a lover, smoking a joint, and looking at stars, compete with the horrors of war.

“It might seem odd that in cities teetering at the edge of the abyss young people still go to class,” Hamid writes, “but that is the way of things, with cities, as with life, for one moment we are pottering about our errands as usual and the next we are dying, and our eternally impending ending does not put a stop to our transient beginnings and middles until the instant when it does.”

Toward the end of the novel, Hamid intersperses the itinerant love story of Saeed and Nadia with that of an old woman in Palo Alto who had, unlike Saeed and Nadia, “lived in the same house her entire life.” She no longer recognizes her home and concludes that although she has never left her home town, she has, nonetheless, migrated — that migration is inevitable, that “everyone migrates, even if we stay in the same house our whole lives,” that “[w]e are all migrants through time.”

Mushtaq Bilal’s book “Writing Pakistan: Conversations on Identity, Nationhood and Fiction” was published last year by HarperCollins. He recently won a Fulbright grant to pursue a doctorate in comparative literature.

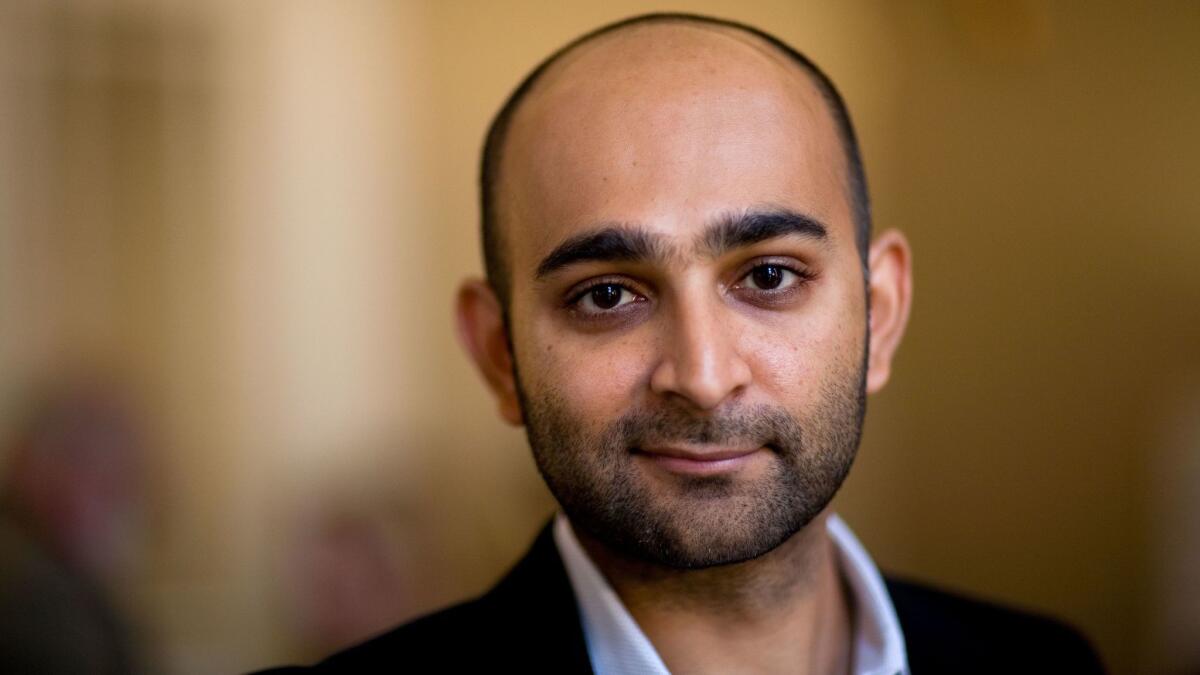

Mohsin Hamid

Riverhead: 240 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.