Ernest Hemingway’s long-lost Los Angeles visit

- Share via

Lots happened in L.A. last night. Lives ended. Lives began. Couples fought, couples made up. A recently transplanted Manhattan-ite said, “All my friends are here!” I probably fell asleep with a book on my chest.

Eighty years from now, what record of these events will survive? Partly that depends on who keeps a diary, who writes to friends or family, who posts, who publishes a memoir and who doesn’t. For instance, 80 years ago this week, Ernest Hemingway, the author of “The Sun Also Rises” and “A Farewell to Arms,” grudgingly visited Los Angeles. He had once recommended the only way for a writer to deal with Hollywood: “You throw them your book, they throw you the money, then you jump into your car and drive like hell back the way you came.”

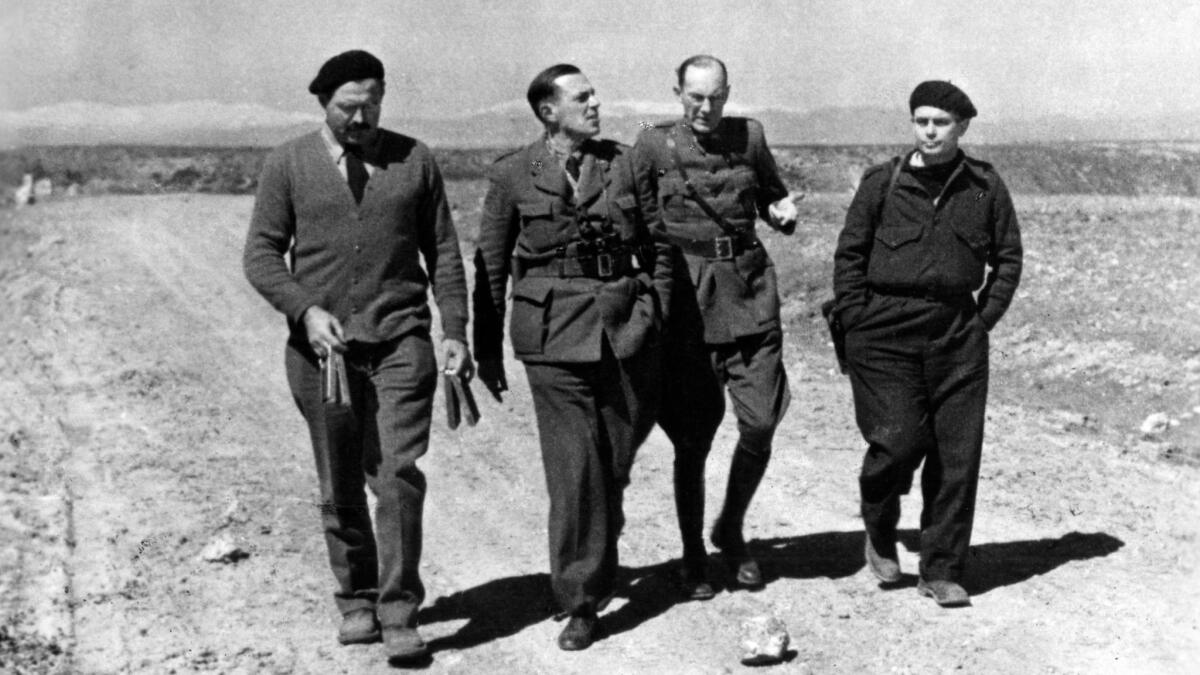

Why, then, did Hemingway make an exception in July 1937? It all had to do with a film that he and Dutch documentarian Joris Ivens had made about the Spanish Civil War called “Tierra de España,” or “The Spanish Earth.” He and a group calling itself “Contemporary Historians, Inc.,” including playwright Lillian Hellman; author of the U.S.A. trilogy (with its Hollywood-themed finale, “The Big Money”) John Dos Passos; poet Archibald MacLeish; and Dorothy Parker (who satisfied all three job descriptions and more), funded the picture out of their own pockets. The idea was to make a movie to raise money for the Loyalist cause. Every $1,000, they promised, would buy a new ambulance.

Fresh off a White House screening for the Roosevelts, Hemingway stayed only a few days in L.A. He made them count, fundraising for the cause everywhere he went.

Hemingway ran the film at the Ambassador Hotel for a starry crowd of 200 at $5 a well-coiffed head. German actress Luise Rainer hosted a luncheon for him in the MGM commissary. Her countrywoman Salka Viertel had him over for show-and-tell with several influential friends at her Santa Monica Canyon house on Mabery Road.

Fredric March, the underrated star of “The Best Years of Our Lives,” “Inherit the Wind” and “Seven Days in May,” invited a few of his politically active colleagues to a showing at his home on San Ysidro Drive in Beverly Hills. Most of the Loyalist-sympathetic Motion Picture Artists Committee were there. Ironically, the benefactors didn’t include Errol Flynn, soon to play Robin Hood, who sneaked out through the bathroom window rather than give to the poor.

Sneak previews successfully behind it, “The Spanish Earth” had its public premiere the next night. Writer Anthony Powell — lately summoned from England as a consultant on “A Yank at Oxford,” and eventually the author of the “Dance to the Music of Time” dodecalogy — sets the scene in his memoir:

“The film was to be shown at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium [just across 5th Street from] Pershing Square, gardens where the bums clustered in the twilight under subtropical boscage. … Outside the hall neon lights shone: HEMINGWAY AUTHOR- SPANISH EARTH.”

At $1.10 apiece, whether for Hemingway or for Spain, 3,000 Depression-era Angelenos turned out. Almost as many were turned away. The seat-hopping scrum delayed showtime for almost an hour. Finally, at 9 o’clock, the lights went down.

“Tierra de España” isn’t the greatest work of art to emerge from the slaughter of the Spanish Civil War (that would be Picasso’s Guernica). Other art about the war means more to more people than Ivens’ film today: George Orwell’s prophetic “Looking Back on the Spanish War” and “Homage to Catalonia”; Joaquin Rodrigo’s lovely if apolitical “Concierto de Aranjuez” for guitar and orchestra; Victor Erice’s “Spirit of the Beehive” and Guillermo del Toro’s “Pan’s Labyrinth,” masterpieces both; and Hemingway’s own “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

Yet “The Spanish Earth,” screening for its 80th anniversary on July 14 at the Norton Simon (as part of a series I curated), repays viewing. It stands as a rare contribution to documentary film by talents far more cherished in other fields.

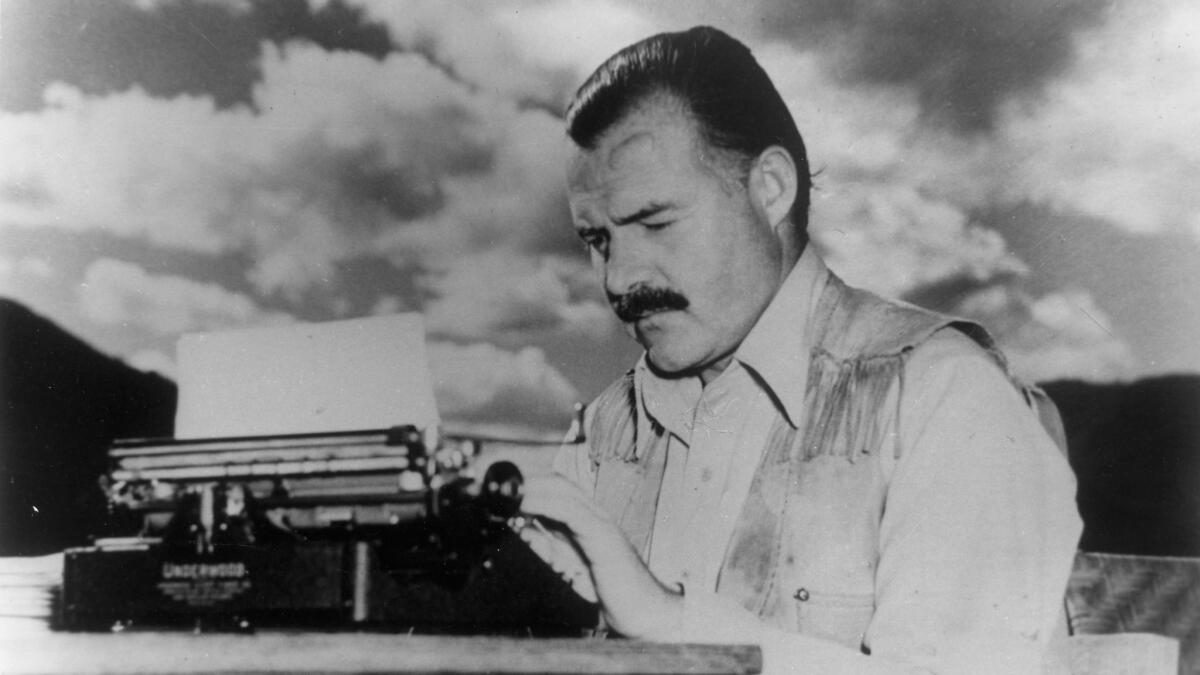

In addition to writing the picture, Hemingway caddied for Ivens across ravaged Spain and narrated it himself in a voice all the more effective for its icy understatement. He had found Orson Welles’ original voicing of the text gushy. “Every time Welles said the word ‘infantry,’ ” Hemingway grumbled, “it sounded like…” well, best leave it to the imagination (and Google) what it sounded like.

After the lights came back up, Hemingway spoke tersely of his experiences reporting the war. Recounting one skirmish, he noted: “Two persons were taken to hospital, the rest removed with shovels.”

The take was brisk. More than a few ambulances were bought for Spain that night. The California journalist-historian Carey McWilliams confided to his diary impressions of the evening and of Hemingway, who had driven ambulances in Italy during First World War before an Italian shell blew his legs out from under him: “Very large fellow — lame. Stood before the stand with his feet spread far apart. He got them together, once, but then he turned ... so they spread apart again. After finishing the paper he turned abruptly and walked off stage. Curious how many faces you come to recognize at these meetings — gets to be a family affair almost.” Afterward, a few of these faces repaired to Dorothy Parker’s house.

Had everything that supposedly happened that night really happened, the party might still be in progress. Somebody should really drive up and check. According to Hellman’s bestselling account from “An Unfinished Woman,” a sober but shaky F. Scott Fitzgerald drove her to Parker’s place at about 10 miles an hour. They got to the front door just as Hemingway dashed a wineglass into the fireplace. The crash compounded an already considerable shock to Fitzgerald’s system at seeing his former protege so conspicuously the center of attention.

Infamously, nobody on a low-salt diet is in a position to take Hellman’s word for anything. Other attendees confirm that her lover, Dashiell Hammett, picked a fight with Hemingway, calling him out for an inability to write memorable women. Hammett knew a thing or two about memorable women, having created the duplicitous Brigid O’Shaughnessy in “The Maltese Falcon” and witty, waspish Nora Charles in “The Thin Man” (partly based on Hellman herself) before subsiding into his final, decades-long creative silence.

Before Hammett could make his case against Hemingway in greater detail, he drank himself into a stupor. He wrote a check as big as an ambulance before he hit the couch.

Let the last word go to the best writer. The next day, Fitzgerald wired Hemingway, “THE PICTURE WAS BEYOND PRAISE AND SO WAS YOUR ATTITUDE.” That same week, Fitzgerald wrote his editor, Maxwell Perkins, that “Ernest came like a whirlwind. … I felt he was in a state of nervous tensity, that there was something almost religious about it.”

One man’s religion is another’s footnote. A day later, Fitzgerald dragged himself to a Bastille Day party at humorist Robert Benchley’s villa in the Garden of Allah at Sunset and Crescent Heights and first locked eyes with British newspaper columnist Sheilah Graham.

At the time they met, Fitzgerald was likelier to need an ambulance than buy one. He would die of a heart attack three years later in her Laurel Avenue apartment, reputedly either listening to Beethoven’s “Eroica” on the radio, eating a sandwich from Greenblatt’s around the corner, poring over the Princeton alumni magazine, or all three. By then he had given Graham a lifetime’s worth of love and aggravation. All she gave him in return was enough of the peace he needed to write most of his brilliant Hollywood novel, “The Last Tycoon.”

History doesn’t happen in a vacuum bottle. You can look up at least a page or two about Hemingway’s public screening of “The Spanish Earth” in any decent biography. (Another two came out just this season. Not bad for a sexist has-been.) You can read about Fitzgerald and Graham in her book about their affair, “Beloved Infidel” — or in “College of One,” her sadly out-of-print account of the literature syllabus he devised for her so she could keep up with him.

Hardly anywhere would you learn that Hemingway’s screening and the Fitzgerald/Graham rendezvous happened on consecutive nights.

Hammett, Powell, McWilliams, Hellman, Fitzgerald and all the nameless rest. The infinite interweaving of lives with lives — lost to illness, lost to war, or simply lost to history. As in Tom Waits’ great lyric, cultural historians lurch from diary to letter to self-serving memoir like drunks “using parking meters for walking sticks.”

Inevitably, necessarily, we get the story wrong, or backward, or worse, and always incomplete. Where are all the volunteers’ grandchildren whose lives Dashiell Hammett’s ambulance saved? There must be dozens. What did they do last night?

And did they write it down?

Kipen’s “Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters” will be published next year by Modern Library. He is the founder of Libros Schmibros Lending Library in Boyle Heights, a lecturer on the UCLA faculty and one of The Times’ Critics at Large.

ALSO

At 10,000 feet in Colorado’s Rockies, a library takes shape, blending nature and books

The LA Review of Books and USC undertake a summer publishing workshop

The guilty pleasure of reading Hollywood memoirs

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.