From the Archives: ‘Godfather’: The gangster film moves uptown

- Share via

The most revealing thing I can tell you about “The Godfather” is that it cost $6 million and has already brought in more than twice that — $13 million in advance payments from exhibitors eager to play what they’re betting will be a walloping great hit.

And they’re absolutely, 100% right, as local audiences will start proving on Wednesday at the Village in Westwood and at Loews’ Hollywood.

Mario Puzo’s novel was an irresistible, eventful, easy-to-digest, hard-to-put down bestseller (a half million hardbacks, 10 million paperbacks) and Puzo and director Francis Ford Coppola, who co-authored the script, have delivered the novel just about as faithfully as a novel can be delivered.

You liked the side action upstairs in the bedroom during the wedding? You got it. Liked the horse-head bit? You got it. The restaurant caper with the crooked police captain? You got it, you got it.

A slam-bang novel with boundless energy and the spicy suggestion that all sorts of secrets are being told under thin disguises has become a rousing movie (a MOVIE-movie, as they say), which seems to me to succeed perfectly at what it set out to do.

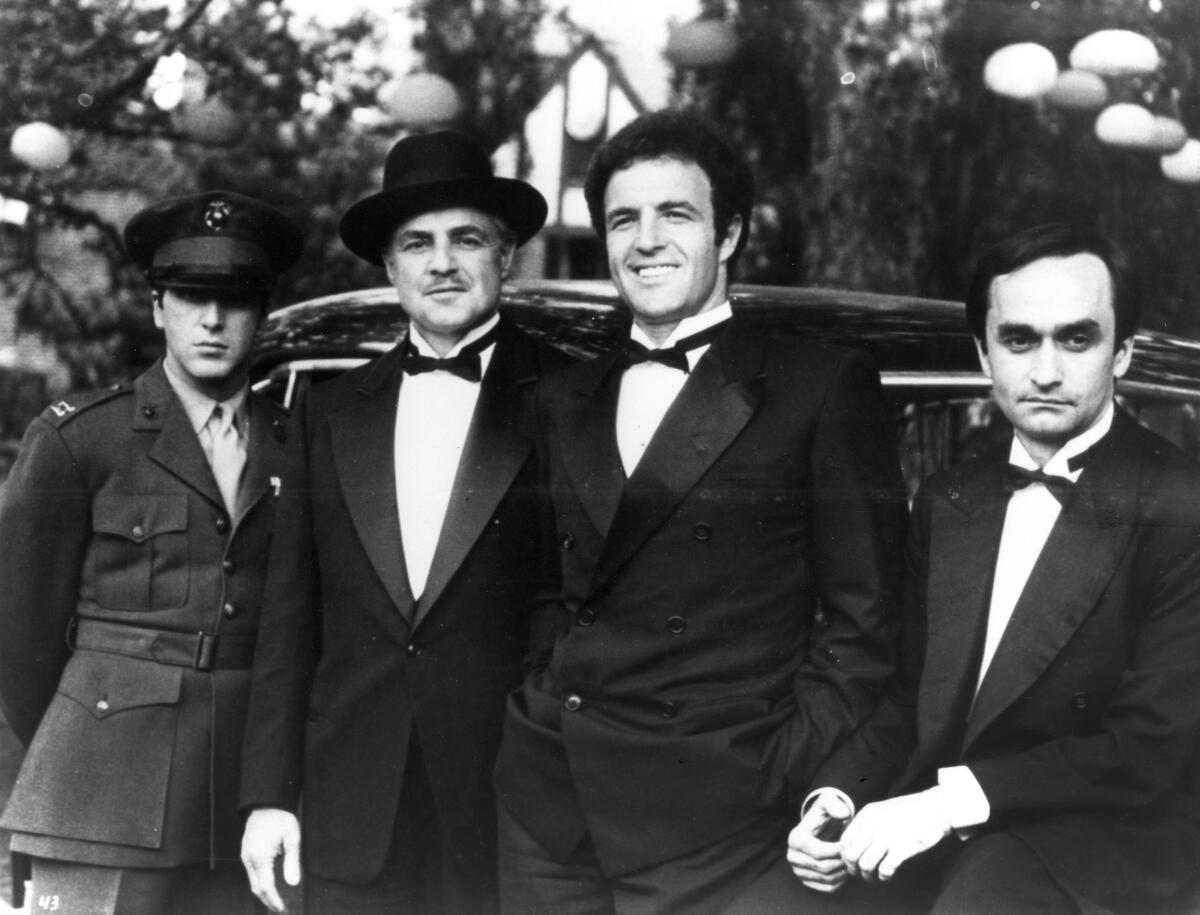

It is marvelously well cast and acted. It evokes a fairly nondescript period in American life — the mid to late ’40s — with unerring fidelity and interest. It is swift and theatrical, probably the fastest three-hour movie in history. It is incessantly and explicitly violent but saves on emotional wear and tear by having the bad guys kill off the bad guys, so what do you care?

As I remember the only innocent who gets it is the nice Sicilian wife who goes to pieces in the car, but that only sets you up for the massive counterblows back home. And that the whole extravagant operation is so Little Caesarean that to respond to it anywhere near the threshold of pain is like reading Harold Robbins for symbols. It misses the object of the enterprise.

“The Godfather” is an entertainment, not a documentary, however close it may come to some of the realities behind the headlines. Because it generates an aura of considerable believability, it is a saving grace of the movie that it keeps its balance.

If, that is, we develop a kind of admiration for Don Corleone and then his sons of protectors of their family, “The Godfather” reminds us — brutally — that they are corrupt and merciless murderers, pimps, peddlers and thieves. The wistful talk about going respectable precedes the further assassinations. Unlike Bonnie and Clyde in Arthur Penn’s movie, the Corleones have not been absolved by being explained in a social context, but like Bonnie and Clyde they have been humanized.

Marlon Brando, his voice a reedy whisper, his jowls stuffed to a patriarchal sag, his body stiffened with years, his hair etched with gray, gives a performance which is at once a tour de force and so economical that it seems to be understated. He does not so much appear to act as to establish and exist as a presence, a strength.

The picture opens with a whiny supplicant pleading to the camera. The camera edges sideways, making us aware of a bulky silhouetted listener. The speaker verges toward tears. The listener raises a hand, makes a small, imperial, beckoning gesture. Someone noiselessly fetches the speaker a steadying drink. After the long, theatrical buildup, the camera pulls back, confirming what we knew and we’re impatient to see for ourselves: The listener was Brando as Don Corleone.

It is one of those special moments to the movies, reminding you what tingling power a star can transmit from the screen — and what a potent star actor Brando is when the material is to his measure.

Grateful viewer

Toward the end of “The Godfather,” Brando as an old man in semi-retirement plays with his grandson in the garden. The sequence seems in part to have been improvised. It is so natural, so charming, so totally the character, rather than the actor acting, that you can only be astonished and grateful to watch such a talent. It is a moment of affecting power such as I have not seen him equal since his classroom soliloquy in “Reflections in a Golden Eye.”

His Don Corleone is a portrayal which reveals more than pages of dialogue could hope to convey.

Hardly less persuasive is Al Pacino, who is first-rate as a young addict in “The Panic in Needle Park” and who as the don’s son, Michael, drawn reluctantly into the family affairs, seems to change from within, even as we watch him, from the nice normal guy to an ice-hearted and methodical murderer who can impassively serve as godfather at a christening while his rivals are being systematically gunned down in at least two states. Pacino makes Michael an even nastier piece of business than his father had been, colder and, once committed, less touched by a common humanity.

(Simply because it is a movie, with the movie’s impact, “The Godfather” here seems to offer less forgiveness, less hope of amelioration or change in the Mafia — the word is never used — than I remember in the book.)

The supporting gallery is large and terrifically effective. James Caan is excellent, again, as the don’s hot-tempered son, Sonny. Robert Duvall is very strong (tough but capable of feeling) as the adopted son who is the family’s lawyer. Richard Castellano, from “Lovers and Other Strangers,” is undemonstrably solid as a henchman and professional wrestler Lenny Montana is very persuasive as another.

Sterling Hayden and John Marley have what amount to cameos as a crooked cop and a studio boss, respectively, and both are fine. Two offbeat castings work very well: singers Morgana King as Brando’s wife and Al Martino as the Sinatra-like figure Brando helps.

Diane Keaton, in her first film, is authentic as Pacino’s WASPish New England wife. Simonetta Stefanelli has a charming innocence as his luckless Sicilian wife.

Richard Conte as a rival chieftain and Al Lettieri as a traitorous henchman, Gianni Russo as a traitorous son-in-law and Talia Shire as his wife are all vivid. John Cazale as a weak brother and Alex Rocco a Las Vegas hotelier both are impressive in large and admirable company.

The technical aspects of “The Godfather” all struck me as upholding the best traditions of the form. The production design by Dean Tavoularis, the art direction by Warren Clymer, the set decoration by Philip Smith and Anna Hill Johnstone’s costumes all conspire to evoke a kind of awkward age too different to be the present but too close to be the colorful past.

The music by Nino Rota (who also did “8 ½”) is remarkable for its grace and unobtrusiveness. It is nicely understated.

Gordon Willis did the photography, which seemed to me to vary to fit the time and the mood. The earliest scenes have a reddish tone that suggests garish early screen color. The wedding exteriors have the squinty, overbright look of home films. Sicily shows under the island’s dazzling white sunlight, and so on. William Reynolds and Peter Zinner edited.

Francis Ford Coppola on this evidence can cope with the spectacle film both as writer and as director. The pleasure of the film is that the performances by Brando and Pacino, strong and vivid as they are, do not overweigh the work of the ensemble. The consistency of texture is an index of Coppola’s skillful control. He has indeed brought off an assured and richly detailed piece of movie storytelling on a massive scale.

The violence, I had better repeat, is violent and graphic, and it is part of the movie’s considered and considerable lure. We are back in the tradition of the gangster film, if in a much tonier neighborhood.

“The Godfather” becomes an instant classic among the superflicks.

Albert S. Ruddy produced for Paramount.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.