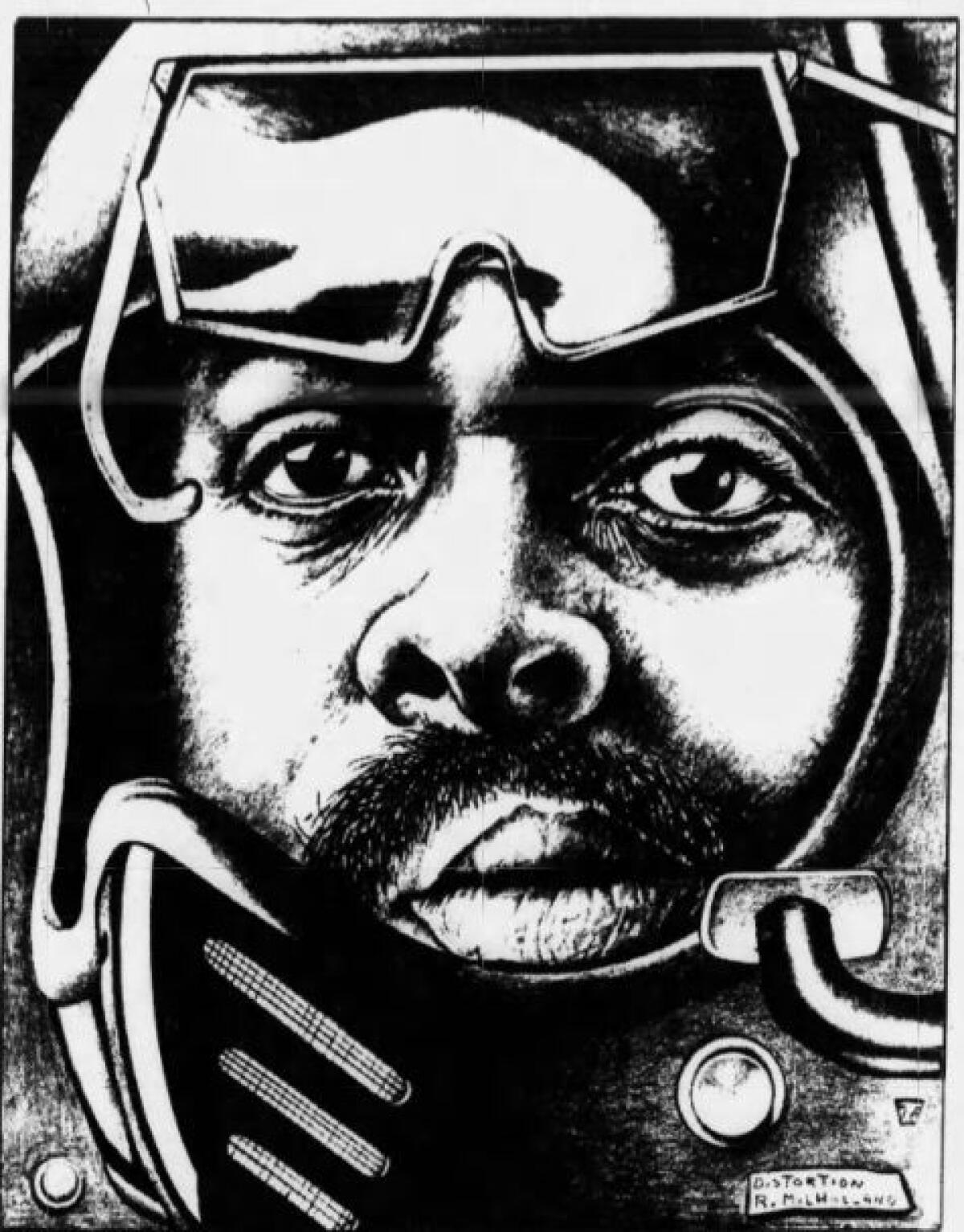

The media’s treatment of Blacks: A story of distortion

- Share via

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. We have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

In 1933, the Los Angeles Sentinel, then the newest black-owned weekly in a growing city of 1.3 million, started a “Don’t Spend Where You Can’t Work” campaign.

Its aim was to stop Los Angeles’ estimated 50,000 black residents from patronizing white-owned businesses on Central Avenue, the heart of the city’s black community, until those businesses hired blacks.

During the boycott, the Sentinel, which started life as the East Side News, saw its founder and publisher Leon H. Washington jailed after the owner of one of the stores being picketed complained to police. In a Jan. 26, 1934, front-page editorial, the Sentinel responded to the jailing of its publisher:

“The Sentinel is not frightened by this show of force. Until Mr. Zerg (owner of a Central Avenue furniture store) and other merchants guilty of discrimination abandon their policy, this newspaper will continue to advocate that Negroes withhold their patronage. Economic self- preservation demands that.”

But not everyone saw the moral and economic issues that the Sentinel saw.

That same year, in its Sunday magazine, the Los Angeles Times profiled Central Avenue without any hint of urgent problems to be resolved:

“Droves of pickaninnies romp in the streets, the thundering trucks of commerce lending zest to their games,” The Times said.

“... There are Negroes who shuffle; Negroes who prance; some look like amiable scarecrows, others like fashion plates. Everybody’s humming a tune. One and all they are taking life as they find it, not with oriental apathy or Caucasian complaint, but with a cheerful acceptance that bespeaks internal sunshine.”

It sounds so insensitively racist by the standards of 1982. But have things really changed that much?

In almost every area of life, large numbers of blacks argue persuasively that the white-owned media, while improved from the slanderous, race-baiting days of the ‘30s, still routinely distort the fabric of black life — when they aren’t neglecting it altogether.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

The complaints are as true for blacks inside the nation’s newsrooms as for those outside. They are voiced constantly at meetings of the two dozen or so black journalists’ organizations that have formed in various cities, including Los Angeles.

Black reporters at a number of newspapers, including the New York Times, the New York Daily News, the Washington Post, the now-defunct Washington Star and the Los Angeles Times, have filed class-action suits or individual claims against the newspapers.

Some blacks who have reached very high media positions — like ABC network news anchor Max Robinson — remain outspoken critics of the ability of their institutions to deal fairly with blacks.

The problem today is not quite as likely to be blatant racism, although that is still common. It’s more likely to be distortions of the truth that rob all Americans, including blacks, of an understanding of the history, the problems and the joys of black life.

There are distortions of the present, as when the media either ignore problems in black communities, or don’t like to discuss such underlying causes of discrimination as white-controlled economic systems, or policies imposed by majority white school boards or city councils.

There are distortions of the past, as when attempts to desegregate Los Angeles city schools get reduced to arguments over “forced busing.”

When conservative black economists made news a year ago by supporting President Reagan’s economic policies, most news stories cast the issue as a political dispute among blacks, ignoring its links to an old and influential steam of black conservatism that has been part of the debate over racism since slave days.

There are distortions of culture and life styles, as when Bo Derek was given credit for popularizing cornrows as a hair style when in fact they had been the rage among blacks for years.

Some distortions seem permanently engraved in American culture, as in all the stories calling Elvis Presley the king of rock and roll, but conveniently ignoring the fact that he borrowed key elements of his style and much of his material from black musicians whose performances seldom reached mass white audiences because of the segregated play-lists on pop radio stations that continue to this day.

Black success stories, absent from the media until recent years, still tend to be highly predictable. Entertainment and sports figures are common. So are politicians and people who fall into the category of interesting oddities.

But stories reflecting victories of that sort are hard to find.

Also common is a failure to cover events that would be covered in white neighborhoods, a failure to feature interesting black people just because they are interesting, as is done with whites.

The media often miss the chance to make sure there is black participation in a variety of stories, such as comment from local citizens on the latest change in interest rates, or the state’s fiscal problems.

Or the media make the mistake of always quoting the same three or four black leaders, erroneously assuming that leadership isn’t as varied among blacks as it is among whites.

Little notice is paid to the routine racism that so many blacks say they have to deal with nearly every day.

And when there are stories, they tend to come in widely spaced special features or packages, instead of routinely as the problems warrant.

When you compare the media’s lack of sensitivity in 1982 with stories such as The Times’ 1933 profile of Central Avenue, it is easy to understand why so many blacks had and still have bitter feelings about white-owned media, including radio, television and movies.

It’s a sensitive issue because the media are such a powerful force. They play a key role in what we think about other people, especially because the country is still not enough of a melting pot for most of us to know personally large numbers of people from other ethnic cultures.

Even blacks who can talk non-stop about how much they hate the media treatment of their communities concede that some media outlets do very good stories on black life.

“It can be a real love-hate relationship,” said one avid newspaper reader.

The twin roots of the problem are little different now than they were in 1933. The lack of enough time and space for the media to cover everything that is newsworthy, and the unfamiliarity of the media’s almost entirely white decision-makers with people different from themselves.

Some critics add a third root: A scramble for profits and ratings that seems to be sending media managers chasing after “upscale” consumers while ignoring other groups.

This reduces coverage of working people and the poor. And when media managers don’t make a conscious effort to remember that there are “upscale” blacks with a lot of money to spend, it reduces coverage of all classes of blacks.

When The Times’ Central Avenue profile was published in 1933, the white-owned media were, for the most part, almost sworn enemies of black people, accepting racial injustice and legal segregation as completely and as unquestioningly as any other American institution.

Newspapers in those days followed a long line of insulting practices, including using “Mr., Mrs.” and “Miss” for whites, but not for blacks, always identifying blacks by race, making a point of publishing stories when blacks were accused of crimes against whites, refusing to take seriously what blacks said about problems they faced, and running articles and cartoons which reinforced the worst stereotypes.

Judging from a variety of polls and surveys, and the comments of blacks who range from ordinary to VIPs, the media today have moved to the uneasy position of an old enemy who talks about seeing the light, but still slips into old habits much too often to be trusted.

One reason is that the media in 1982 remain one of the more segregated American institutions, especially at decision-making levels.

Los Angeles, for example, unlike other major cities, has no regularly scheduled black TV news anchors during the week in early evening prime time. That situation has been a low-grade sore point for years among the city’s black-establishment leadership.

There are two black news-assignment editors at KNX radio, and from time to time weekend staffs at various TV and radio stations get so black that terms like “weekend ghetto” come into use.

But there are no blacks who have regular access to the daily editorial meetings where local newspaper editors decide which stories will get space, and where television executives decide which stories will get covered.

Both KNXT and financially troubled KCET have black station managers (at KNXT, the station manager is the former news director). But they do not have daily participation in news decisions.

The latest nationwide survey showed that early this year, only 5.5% of daily newspaper professionals were nonwhite. There were only 106 blacks classified as management scattered among the nation’s 1,745 dailies.

The Los Angeles Times is alone among newspapers in its class in having neither a black writer on its editorial page, nor a senior black editor.

The Times’ highest-ranking black is an assistant Orange County city editor.

Is all of this the result of racism? Or is it just the nature of a business where the mostly white male owners and top editors tend to promote people whose loyalties, personalities and viewpoints they share feel comfortable with?

When white editors hire only blacks with whom they feel “comfortable,” it can filter out some of their personality characteristics that can make a contribution to accuracy in news coverage.

For example, a combination of bravado, cunning, thinly veiled abrasiveness and the ability to “jive” would give a black reporter excellent access to black street life, including gangs and certain of the long-term unemployed.

But that combination, even though it takes nothing away from the ability to report and write well, tends to make white editors who value more timid cultural traits a bit nervous, as black reporters who possess these qualities will say.

To many, all this adds up to a need for more diversity in media staffing.

The Minorities Committee of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, in a study published in May, concluded that the “greatest progress” toward good news coverage was made by editors “who view an integrated news staff as essential to offering their readers the best newspaper possible.”

Robert C. Maynard, editor, publisher and president of the Oakland Tribune, shares that view. Maynard is the first black to head a major metropolitan white-owned daily.

The problem, he says, is “not just about black people, or Hispanics, or poor people or gay people. The problem is an insensitivity to the interests and concerns of non-elites, whoever they may be. The problem of the press in America is the problem of learning how to be relevant to the concerns of ordinary people.”

I remember being shocked in the mid-1960s, when I was running around the country covering urban riots, and found that most of the white reporters I saw, like the white policemen, couldn’t read black faces.

To them all black crowds were “menacing” or “threatening” or “angry,” even when they were mostly neighbors you lived with every day out to see what all the fuss was about.

What can you do with a media institution full of white people who can’t read black faces? The short term answer is, the best you can. But the result isn’t likely to impress black people with its sensitivity, its perception, or its fairness.

One of the more recent examples of media insensitivity was a major investigative story published by The Times more than a year ago, with no participation by its own black reporters or editors.

According to the article, entitled “Marauders From Inner City Prey on L.A.’s Suburbs,” a “growing wave” of black and Latino youths were leaving their neighborhoods, “staging areas for robbers and burglars and thieves,” and riding the freeways “like magic carpets” to the suburbs where they would wreak “senseless savagery” on white residents.

When the article was printed, blacks, and many whites, were irate. When the Society of Professional Journalists, Sigma Delta Chi, included the “Marauders” story in a public-service award to The Times this spring, a joint protest letter was sent by the boards of directors of the Black Journalists Assn. of Southern California, the California Chicano News Media Assn. and the Asian American Journalists Assn.

The “Marauders” story also won another award this year. The National Assn. of Black Journalists voted the story the “Most Objectionable News Story” of 1981.

Such shortcomings of the media in covering blacks frequently cause a warped image of black life to be published or broadcast. Even white editors who participated in the ASNE’s study agreed that their papers were not presenting a complete-enough picture.

Dr. Brenda Wall, a psychologist who specializes in the consequences that arise from media distortions, believes that “generally, in entertainment as well as on the news … black experiences aren’t shown, subtle interactions aren’t shown … because a lot of humanness is missing. Our values are missing.”

By all accounts, correcting these problems in the years to come will not be easy.

According to the ASNE study, the rate at which newsrooms are being integrated has been dropping steadily for the past five years, precisely the years when the most concerted effort was being made.

If things continue as they are going, the report concluded, there may not be a representatively integrated newspaper industry in this century. At present, it said, only 40% of daily newspaper newsrooms have integrated staffs, and the percentage has never been higher.

Strangely enough, major Southern California newspapers from Santa Barbara to San Diego, including The Times, did not carry that report when it was issued at the ASNE’s May meeting in Chicago. Neither did the New York Times nor the Washington Post.

Campaigns like the Sentinel’s “Don’t Spend” crusade were once a common way of keeping portions of the black community welded into a force that could fight for change.

But the number of black newspapers, their income and the power they are able to wield has been dropping steadily for a generation.

Black communities are more diffuse than they used to be as housing segregation slowly breaks down. And the white-owned media have found it particularly difficult to understand the needs of such a diverse audience.

According to national media critic Ben Bagdikian, who teaches journalism at UC Berkeley, the “moral obligation” for general-circulation newspapers to cover minority groups is relatively new.

It started after World War II, he said, when the trend for competing newspapers to kill each other off until there was a monopoly of one in medium-size cities became permanent.

When cities of 100,000 to 200,000 population had as many as four or five newspapers, Bagdikian said, each intended to aim at different groups of people, so that collectively they “would reflect the interests and needs of something like the total community.”

But there are now competing newspapers in “fewer than 2% of our newspaper cities, “ Bagdikian said, and “American local broadcasting has failed to create a comprehensive news system in any way comparable to newspapers …”

While it is “generally agreed upon by most newspapers and their staffs that they should serve the whole community,” Bagdikian said, he knows of none performing the task well.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.