Brookledge, Hancock Park’s magical home

- Share via

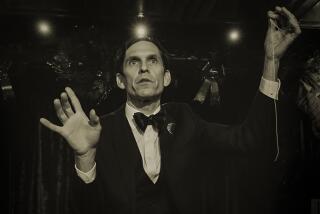

The flickering light of a dozen dripping candles illuminates magician Rob Zabrecky’s gaunt visage and pronounced brow. Wearing an old-fashioned tuxedo, he resembles a cross between a 1920s vaudevillian and Lurch from “The Addams Family.”

“Welcome to the most famous address in magic: Brookledge,” he intones from the stage of an antique theater located behind a Spanish-style mansion in Hancock Park named Brookledge.

It’s a Friday night, and the 70 guests, all here by invitation, are insiders in the mysterious yet thriving world of illusion in Los Angeles. They’re also witnesses to an effort to revive a lost era of legerdemain.

The old-school variety-and-magic show, called the Brookledge Follies, unfolds slowly and deliberately, like a polished card trick. The air in the small room is warm, the vibe intimate. When Michael Carbonaro of the Blood Brothers determinedly swallows sewing needle after sewing needle while his partner sucks up a long piece of string, the audience recoils in empathetic pain.

Then Carbonaro and his partner lean together, kiss and pull apart, each holding an end of the string in his mouth, to reveal that it is strung with the sewing needles. The audience gasps, laughs and claps wildly.

Actor and musician Ryan Gosling is in attendance, along with a well-dressed assortment of sword swallowers, burlesque dancers and yo-yo enthusiasts. Gosling’s ghost-obsessed indie rock band, Dead Man’s Bones, was heavily influenced by an earlier visit to Brookledge by Gosling and bandmate Zach Shields.

“We fell in love with the place and what was happening here,” says Gosling, who is dressed in black.

What is happening at Brookledge is vintage magic’s last stand against magic’s modern reincarnation as pure spectacle.

Magic went mainstream around the turn of the 20th century and thrived until the 1920s and ‘30s, when movie palaces began encroaching on magic theaters. Then the art of illusion began a slow march backstage and into a niche subculture. Entertainers such as David Copperfield pushed it back into the limelight in the 1980s and ‘90s, but at the expense of its intimate scale and burnished technique.

The magic of the small stage, of vanishing doves and mysteriously procreating rabbits, gave way to Big Magic, also called large-scale illusion. The artful execution of tricks was eclipsed by elaborate feats: going without food for 44 days while suspended in a plexiglass box or making the Statue of Liberty seem to disappear on live TV (a Copperfield production).

As magic moved closer to performance art, it became more television-friendly but lost the quiet determination of craft.

The craft itself — the technical skill that, when practiced correctly, goes entirely unnoticed — is what magicians value above all else and what the monthly, invitation-only shows at Brookledge aim to revive.

Eventually, the producers plan to move the Brookledge Follies to a larger venue and sell tickets to the public. But for now, the productions are small, unpublicized affairs, intended to enhance a sense of community among those wishing to rediscover the golden age of magic.

To these purists, Brookledge matters. That’s because it is the home of Irene Larsen, who with her late husband Bill and his brother Milt co-founded one of the world’s most famous private magic clubs: Hollywood’s Magic Castle. Bill and Milt were raised in Brookledge.

Erika Larsen, the 42-year-old daughter of Irene and Bill, came up with the idea to stage vintage shows at the mansion. She grew up in Brookledge, a child of magic, and became a member of the Magic Castle’s board of directors.

She met Zabrecky, a musician, actor and magician, about 10 years ago at the Castle and the two became friends. When she hit on the idea of the Follies, she turned to Zabrecky to help flesh out the concept and act as host.

Irene opened her home to the Follies about a year ago. It was the first time Brookledge’s theater, a historic landmark, had been used for live magic since its heyday in the 1940s and ‘50s.

The Follies are dedicated to the notion that in an age when the digital effects in movies such as “Avatar” can seem like magic, genuine, old-fashioned magic — sleight-of-hand and the real-time delivery of illusion — can still exert a powerful hold on the imagination.

“The people who find their way to Brookledge appreciate the vintage aesthetic of the entertainment,” says Zabrecky.

The show gets its audience strictly by word-of-mouth. Admission is free but you must be invited by a performer or by a guest who has been invited by someone on the inside.

Judging by the current craze for things supernatural and magical — the HBO series “True Blood” and the “Twilight” series of books and films are just the beginning — Zabrecky’s and Erika Larsen’s timing seems inspired. So does their approach: The Follies seamlessly blends the spirit of a magical and mysterious past with the winking, self-acknowledgment of the present-day world of illusion.

By dressing the show up to look and feel vintage, its participants can lay claim to the rich, kitschy history of magic while performing first-rate, contemporary tricks. In other words, they can have their cake and disappear it too.

“I think it’s wonderful what the kids are doing,” Milt Larsen, now 79, says of his niece, Zabrecky and their creative partners in the Follies, co-producer Jeremy Kasten and musical director Kristian Hoffman. “They’re utilizing that crazy little theater totally off the radar in what you could call the most respectable of millionaire alleys.”

Zabrecky, 42, was frontman for the popular indie-rock band Possum Dixon in the 1990s. During one of the band’s last tours, he happened onto a magic shop in Baltimore and bought a simple trick — a vanishing silk handkerchief. He performed the trick onstage that night using a condom instead of a handkerchief, and after that he was hooked.

When the band broke up, Zabrecky made it his mission to become a magician member of the Magic Castle, eventually earning a place as one of its core performers. He insists that the purpose of magic is not to fool people into thinking an illusion is real, but rather to astonish, to reintroduce a state of “childlike wonder.”

The first Brookledge Follies show was staged last October and was in the form of a vintage spook show.

“Spook shows just kind of died off. They had a real shelf life,” says Zabrecky.

The formula is one Erika Larsen knows well. When her mother immigrated to the United States from Germany in the late 1950s, she and her husband toured the country performing in spook shows, which pivot around a well-timed blackout during which ghostly effects are triggered and spirits appear to enter and toy with the room.

During Brookledge’s first spook show, the audience was introduced to two showgirls who supposedly had recently returned from a trip to Africa. They brought a gorilla with them (actually, a magician in a gorilla suit), and the gorilla got loose. Zabrecky then pursued it. “I fired up a gas chainsaw and as I revved it and rushed into the audience, the blackout occurred,” Zabrecky recalls.

The effect was electric, and the Follies became a monthly affair. They aren’t all spook shows; some, like the one Gosling attended, lean heavily toward the variety arts.

Brookledge, built in 1937, has been filled with magic from the beginning. Its first owner was Floyd Thayer, who manufactured high-end magic equipment. In 1942, Thayer traded homes with William W. Larsen Sr., father of Bill and Milt. The elder Larsen ran Genii magazine, which he founded, out of Brookledge.

Thayer’s Studio of Magic, as the home theater was called, was a showcase for magicians, including Blackstone and Dante, who came to test their illusions on the stage. During World War II, Orson Welles rehearsed his USO tent shows with Rita Hayworth, Joseph Cotten and Marlene Dietrich at Brookledge. That era is marked by an old green-and-gold sofa, called the Orson Welles sofa, which sits against a wall at the rear the theater.

In the backyard after a recent Brookledge Follies show, performers and guests chatted and sipped drinks beside a brook that runs through the yard. A garden composed entirely of gnomes collected by Irene and Erika glowed in the moonlight. Zabrecky reveled in Brookledge’s illustrious past and his pleasure at its current reincarnation.

“I’m the luckiest guy in the world because I get to host it,” he says of the Follies. “You can’t believe you’re there and then this odd man comes out on stage, and wow, I’m that odd man. I have to suspend my own disbelief.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.