A scary world since 9/11

FOR a government so obsessed with secrecy that it has weighed prosecuting reporters for espionage, George W. Bushâs administration has spawned an extraordinary number of what are essentially book-length leaks.

Partly, thatâs because fortune has summoned this White House to govern in wrenchingly dramatic times, and even serious people are inclined to talk about exciting things. Partly, itâs also because this administrationâs decisions and the way it implements them seem to have left an extraordinary number of disillusioned and disgruntled people in their wake.

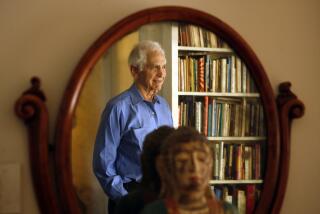

Ron Suskind was a Pulitzer Prize-winning Wall Street Journal reporter and âThe One Percent Doctrine: Deep Inside Americaâs Pursuit of Its Enemies Since 9/11â is a richly detailed and layered account of what some of the best-placed among the disgruntled say has occurred behind the scenes since the terrible events of Sept. 11, 2001. It makes for deeply unsettling reading and is a major contribution to our national conversation concerning these issues.

The title is borrowed from a formulation attributed to Vice President Dick Cheney that has mutated from a response to one situation into a generalized administration policy: âIf thereâs a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping Al Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response. Itâs not about our analysis.... Itâs about our response.â

Suskindâs reporting has led him to believe that the adoption of that standard as national policy had deformed both the conduct of the war in Iraq and our response to the international threat of terrorism by Islamic extremists. His book is replete with grippingly detailed examples, the most sensational of which has been the subject of considerable news coverage based on a pre-book publication excerpt in Time magazine. That, of course, is the story of how Al Qaeda came within a little more than a month of using a workable device it had developed to unleash poison gas in the New York subway.

It is one of Suskindâs provocative conclusions that the terrorists called off this attack for reasons of their own and that the Bush administrationâs election year claim to have prevented any attack on U.S. soil since 9/11 was delivered in the knowledge that this was so.

Similarly, the White House claim that Libya abandoned its effort to build atomic weapons as the result of the U.S. overthrow of Saddam Hussein is -- according to this account -- willfully false. Tripoli, this book argues, took the decision in response to a long and extraordinarily adroit CIA infiltration of their Pakistani supplierâs efforts to spread nuclear technology.

There also are additional details on how the Bush administration essentially appropriated the Sept. 11 attacks as a rationale for Cheneyâs and Donald Rumsfeldâs long-held desire to invade Iraq and topple Hussein.

Thereâs more, as well, on how evidence concerning Baghdadâs alleged pursuit of weapons of mass destruction was distorted and misused to sell the war to the American people.

Most disturbing, there is important new information -- gleaned mainly from Saudi Al Qaeda operatives -- on how the terrorists hoped the United States would invade Iraq and become bogged down there.

There also is a good deal of usefully high-level introspection on what it means to navigate these troubled times dependent on dictators, on inherently unreliable Mideastern and Central Asian allies, and on the post-9/11 evolution of Islamo-fascist terrorism.

Inevitably, what one makes of a story like this as we all (to gloss Suskindâs phrase) blindly make our way through the age of terror depends on how you assess the authorâs sources.

Unlike other books that have preceded this one, the author does not rely wholly on unnamed sources, which is entirely to his credit as a reporter and adds immeasurably to this bookâs effect.

Other sources are transparently easy to figure out, even for semi-serious readers of the news. In an authorâs note, Suskind writes of ânearly one hundred well-placed sourcesâ and describes them as âformer officials with the CIA, the FBI, the White House, and also with the NSC, the State Defense and Treasury Departments and assorted others.â

Overwhelmingly, however, this book is an account of the world since Sept. 11 from the perspective of the professional U.S. intelligence services, mainly the CIA and its former chief George J. Tenet, who is said to be working on his own memoir. The situation of these sources is something that demands to be taken into consideration.

Itâs obvious that Suskind admires his sourcesâ intelligence and candor -- and not simply because they told him things he could write.

As he notes at one point: âThe pressures of fighting an elusive enemy from within the passive-aggressive realm of bureaucracy were particularly acute.... Depression anxiety disorders and suicide attempts raced through the cubicles, and even into some upper offices. In April 2003, the head of the FBIâs unit on Hezbollah and radical Shiite fundamentalists took his own life with his bureau-issue revolver.â

Similarly, his account of what happened to the CIAâs analytic chief Jami Miscik, when she rejected then-CIA Director Porter Gossâ demand that she agree to Cheneyâs demand to declassify misleading intelligence, is sobering.

On the other hand, Suskind does not hesitate to depict Tenet and his senior aides sitting around the pool of a villa as secret guests of then-Saudi Ambassador to Washington Prince Bandar bin Sultan, enjoying their hostâs brandy and cigars and bemoaning their situation.

Itâs not a picture likely to engender confidence in those concerned about either the CIAâs performance or the ambiguities of the U.S.-Saudi relationship, as Suskind most certainly is.

At the risk of sounding like one of these wheels-within-wheels intelligence types, one of the reasons Suskindâs account seems like a reliable recitation of his sourcesâ version of events is that analysis -- that is, teasing the significance from his material, let alone bending it to a purpose -- clearly is not his strong suit.

This author is a gifted and enterprising reporter and those attributes inform nearly every part of this important book. Its analytic forays, although brief and measured in tone, tend toward density and convolution. The point of measuring Bushâs conduct against the moral standards of Mahatma Gandhi, for example, seems ... well, slightly beside the point. Yes, there is a discrepancy, but itâs rather like the one discovered by comparing apples and Abrams tanks.

At the end of the day, this compelling book seems to offer a choice: The dissidents and the disillusioned within the intelligence agencies are correct, and the Bush administration has screwed up both the war in Iraq and the struggle with Al Qaeda and lied about it to retain power.

Or, Bush, Cheney and Rumsfeld were forced to confront an unprecedented security threat with dysfunctional weapons inherited from an earlier war and have bruised a lot of egos and careers as theyâve struggled against an enemy whose emergence nobody foresaw.

It is a measure of Suskindâs accomplishment that when youâve finished âThe One Percent Doctrine,â you are willing to entertain the genuinely chilling possibility that all these things might be true.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.