Making Some Noise

ALBUQUERQUE â It happened on an otherwise ordinary Thursday night in this desert city -- a classic bit of March Madness.

In a regional semifinal game, underdog West Virginia was making three-point shots one after another, playing textbook basketball, building a lead. Meanwhile, favored Texas Tech was coming unglued, causing Coach Bob Knight to scream at anyone within range.

And the fans in the cheap seats were loving it.

These were locals, some of whom had bought tickets a year in advance, others who lined up at 6 that morning. They had seen neither of these teams before, didnât particularly care who won, yet rose from their seats to cheer.

âI just like good games,â said Charles Montoya, a 42-year-old who had driven down from Santa Fe. âThis is fun.â

To understand what transpired in Albuquerque that night -- and at a dozen other locales during the 2005 NCAA menâs tournament that culminates in St. Louis this weekend -- it is important to recall that only a few months earlier, fans across the nation were arguing over how to pick a champion in college football.

It has become an annual debate, haggling over computer rankings and the sanctity of the regular season, consternation over whether to have a playoff. And every year, just as the commotion dies down, college basketball comes along to remind everyone how to do it right.

No one questions the tournamentâs fairness in producing a champion. No one clamors for a better or more exciting way.

Over the last 30 years, March Madness has grown from a cozy 32-team affair into an event of monolithic proportions. Big crowds, big ratings and a $6-billion television contract are products of the eventâs inherent strengths -- and some shrewd maneuvering by the NCAA and the networks.

âThey basically own March ... and it keeps getting more and more powerful,â said Paul Swangard, managing director of the Warsaw Sports Marketing Center at the University of Oregon. âI liken it to how Hallmark created Valentineâs Day. Itâs a self-created holiday.â

*

Two hours. That is roughly how long it takes to play a college basketball game. And that might be the sportâs biggest edge.

From a purely competitive standpoint, basketballâs conciseness allows the NCAA to cram 65 teams into a three-week schedule. Football, if it were to adopt a playoff of similar length, could include only eight teams, leaving the possibility that one or more deserving schools could be excluded.

In terms of fan appeal, brevity is equally valuable.

Television can show a dozen games in a programming day. Organizers can attract ticket buyers with multiple-game sessions from the first round through the Final Four.

âThereâs just so much action in such a short period of time,â said Tom Odjakjian, an associate commissioner of the Big East Conference and former television executive. âItâs remarkable.â

Another critical element: Unlike the NBA playoffs, this is one-and-done, which amps up the drama. Do you think Bucknell would have defeated Kansas in a best-of-five series?

âThereâs no coming back the next day,â said Larry McCarthy, an associate professor of sports marketing at Seton Hall University. âThe NBA doesnât have that. Baseball doesnât either.â

Over the last three decades, the NCAA has made changes to maximize these advantages.

Starting in 1975, the association threw out a rule that each conference could send only one team to the big dance. How big a difference did this make? Think of classic tournament games. Duke-North Carolina. Michigan-Indiana.

A few years later, officials began the process of seeding and balancing the brackets, moving teams out of their geographical regions.

âIt really started setting up very compelling intersectional matchups in the first and second rounds,â said Dave Gavitt, the former Providence coach and founder of the Big East. âThese were games that you never had before.â

At the time, the networks showed only a dozen or so games each March, mostly on weekends. This was before the proliferation of cable, so ratings were much higher and no one wanted to preempt a hit series -- or even a daytime soap opera -- for basketball.

Then came ESPN, an upstart looking for games to fill its schedule, boxed out of most major events. In 1980, the network signed a deal to televise the early rounds live. âEverybody was excited ... they knew what they had,â said Odjakjian, who worked in programming at the time.

The tournament gave ESPN credibility, and ESPN gave fans their first comprehensive look at the magic of the first and second rounds -- those Cinderella teams and unthinkable upsets.

By 1991, the telecasts were drawing such big numbers that CBS negotiated a contract for exclusive rights to all the games. As television viewership grew, the NCAA kept enlarging the size of the field -- to 40 in 1979, 48 in â80, 52 in â83, 53 in â84, 64 in â85, and 65 in 2001. Again, this served dual purposes.

The more teams involved, the less possibility that a realistic contender would be left out of the mix. And, from a marketing standpoint, the tournament could include schools from dozens of states, drawing on an ever-larger fan base.

âThat generates a lot of interest,â said Osei Appiah, an Ohio State advertising professor who played for a Santa Clara team that lost to Iowa in the 1987 tournament. âIt could only help the popularity of the sport.â

*

Not that everything is perfect with college basketball.

Though overall television ratings for last yearâs tournament increased by 24%, the numbers for the final involving Connecticut and Georgia Tech were the lowest in more than 20 years.

Network executives point out that, with the expanding cable universe, ratings arenât always what they seem. Viewership for last Februaryâs Super Bowl was the lowest in four years.

Of greater concern to basketball officials is an issue familiar to college football.

For all the talk about a potential playoff system extending the football season, taking players away from their studies for too long, NCAA President Myles Brand says that when he meets with university presidents and athletic directors, their biggest issue is the sanctity of the regular season.

With comparatively few games each fall, football has a do-or-die feel each week, an urgency that would diminish if teams and fans knew that a loss, or even two, might not knock them out of contention.

Basketball could not possibly sustain such a high level of drama over a 30-plus game schedule. Yet there is some concern that March Madness has grown so big as to overshadow the regular season.

âPeople are excited today ... but the buildup for the regular season doesnât get started until football is over,â said Greg Shaheen, NCAA vice president for Division I menâs basketball. âWeâre looking at ways to energize the fan base that loves the game but arrives at the party late.â

College basketball doesnât have an all-star game to provide a promotional spike at midseason. It doesnât even have an opening day. And the phenomenon of âMidnight Madnessâ -- fans packing into arenas to watch the first official practice -- is on the wane.

The NCAA has created a panel of coaches, officials and television broadcasters to examine this and other issues surrounding the game.

âYou just canât assume weâll always have this level of high energy,â said Jim Haney, executive director of the National Assn. of Basketball Coaches. âHow do you market the game five years from now? What can you do during the regular season to make it more compelling?â

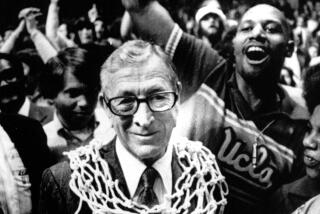

No one is panicking yet. Overnight ratings for this yearâs tournament are up 14% from last year, CBS said. By the time the winning team cuts down the nets after the championship game on Monday night, the network will have televised 66 hours of games.

Speaking this week from the Final Four in St. Louis, Brand expressed a degree of contentment with the way things stand -- in both football and basketball.

âI donât want to assimilate one sport to another,â he said of the debate over a football playoff. âThatâs not to preclude some time in the future that college football will be different, but Iâm not at all dissatisfied with the way it is right now.â

And, at the Albuquerque Regional, there was no telling the players that March Madness wasnât the biggest thing around.

âI remember when I was a kid, I always watched the tournament,â Washington forward Mike Jensen said. âItâs the time of year you get to see all those teams youâve heard about.â

Same for the fans who packed the upper deck, peering down at the court from high above.

âThis is a big deal,â said Chad Hewitt, a teacher from Hagerman, N.M., about four hours southeast of the regional site. âIf youâre a basketball fanatic, it doesnât get any better.â

*

Times staff writer Robyn Norwood contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.