Diary of a life among the Raj

It is not surprising, with Americaâs current interest in central Asia, that the 1839 military disaster for the British that came to be known as the First Afghan War would inspire a new batch of historical novels.

That war occurred during the time of âthe Great Gameâ between Britain and Russia, which were competing for control in this region. At the time, Britainâs top man in India, George Eden, Lord Auckland, made an ally of the Maharajah Ranjit Singh, the aging one-eyed Sikh leader in the Punjab, a strategically significant area that encompassed most of todayâs Pakistan. Eden convinced Singh to help depose the neighboring emir of Afghanistan and replace him with a ruler sympathetic to the British. So in 1839, 30,000 soldiers under British command marched into Kabul to an easy victory. A few months later, resisting Afghans killed the British commander, cut him into pieces, hung his head in a bazaar and sent his army packing, slaughtering stragglers as they made their way through mountain passes. Certainly this devastating miscalculation by the British has relevance today.

What is surprising is that it would inspire âOne Last Look,â the fifth novel by Susanna Moore, author of âIn the Cut,â the edgy, suspenseful and explicit 1995 novel about a writing teacher being stalked by a serial murderer, now a film featuring Meg Ryan. Mooreâs latest is mighty slow going in contrast.

Like another recent novel -- Thalassa Aliâs âA Singular Hostage,â about a young British woman who accompanies Lord Auckland and his sisters to India in search of romance -- âOne Last Lookâ draws from the well-documented personal experiences of novelist, diarist and travel writer Emily Eden, who accompanied her brother, the real George Eden, Lord Auckland, and their younger sister Fanny, to India for his term as governor-general from 1836 to 1842.

The novel takes the form of journal entries by the fictional Eleanor, the older of two sisters who accompany their brother to Calcutta. Moore quotes directly from the real letters, diaries and writings of Emily and Fanny Eden and their contemporary, travel writer Fanny Parkes. But Moore adds her own overlay of family secrets.

Eleanorâs diary begins in February 1836, when she and her siblings have been at sea 72 days. Eleanor is desperately seasick and out of sorts. âEven the moon is hot tonight. The air has thickened. Strange lights play about the ship. Flying fish throw themselves across the bow; the deck is littered with them. It wonât be long now. I can even taste it -- it chokes me. I am pressed against the Eastern Gate. I feel like cutting someoneâs throat. I am shocked at the violence I discover in myself.â

Not what we might have expected from an early 19th century English noblewoman. But neither is her relationship with her brother. Aboard ship, Eleanor spends a lot of time lounging in bed with Henry: âThe ship plowed once more into the sea and I was thrown against Henry, our legs caught in a soundless dance as we rolled back and forth with each lunge of the ship.â

Moore more than hints at incest. Throughout, there are regular teasing scenes in which Eleanor and Henry appear to be involved in sexual play, but the conventions of the 19th century novel, which inform âOne Last Look,â force the author to draw the veil. This coyness sets up an odd sort of tension, an undertone of eroticism that, if nothing else, adds a welcome element of suspense but is not necessarily credible and is never satisfactorily resolved.

Eleanor is an acute observer of the layers of colonial society and of her new home in the âdazzling greennessâ of Bengal, where the air is heavy with the scent of Queen of the Night and the garden harbors a flower-bedecked altar to a Hindu goddess. She has a refreshing sense of irony and a growing awareness of the enticing pleasures of India (including opium, which helps with her headaches) and of the suffering outside the gates of Government House as she travels with her brother.

However, her experience of the Afghan war is secondhand, through letters, dispatches and conversations others have with Henry. âAs I listened to them, I thought that Henryâs way with me ... is not dissimilar to my way with the people. Wary, indulgent, amused, protective, terrified.â

Shortly after an elaborate ball to celebrate Queen Victoriaâs birthday in May 1839, Eleanor notes, âTwenty years ago, no European had ever been here, and here we are ... 105 Europeans surrounded by at least 3,000 mountaineers who, wrapped in their hill blankets, look on at what we call our polite amusements and bow to the ground if a European comes near them. I sometimes wonder they do not cut off our heads and say nothing more about it.â

It is Eleanor, not her brother, who realizes that âsooner or later, they will ask us to go.â By the end of 1839, the British-led âArmy of the Indusâ has been decapitated, and she prepares to head home to London with Henry in disgrace.

The accomplishment of âOne Last Lookâ is a gradual unfolding of sensual detail that is truly transporting at times. In three passionately told novels about Hawaii -- âMy Old Sweetheart,â âThe Whiteness of Bonesâ and âSleeping Beautiesâ -- Moore already has demonstrated her talent at describing the delights and torments of the senses. In comparison, âOne Last Lookâ seems an oddity, a diversion. We have come to expect more. *

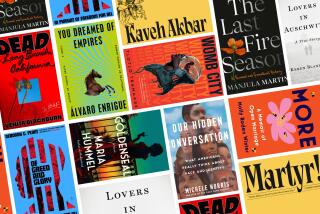

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.