The Thrilla on Katella: How the Angels saved their 2002 championship season

- Share via

This story originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times on March 30, 2003, recapping the Angels’ rally in Game 6 of the 2002 World Series against the San Francisco Giants.

The truly grand games generally distill themselves into images. The final scores fade into footnotes, but the emotions are forever vivid: Bill Mazeroski stomping on home plate, Carlton Fisk frantically waving his arms, Bill Buckner staring helplessly behind him; Kirk Gibson hobbling around first base and pumping his arm twice, Joe Carter soaring on air.

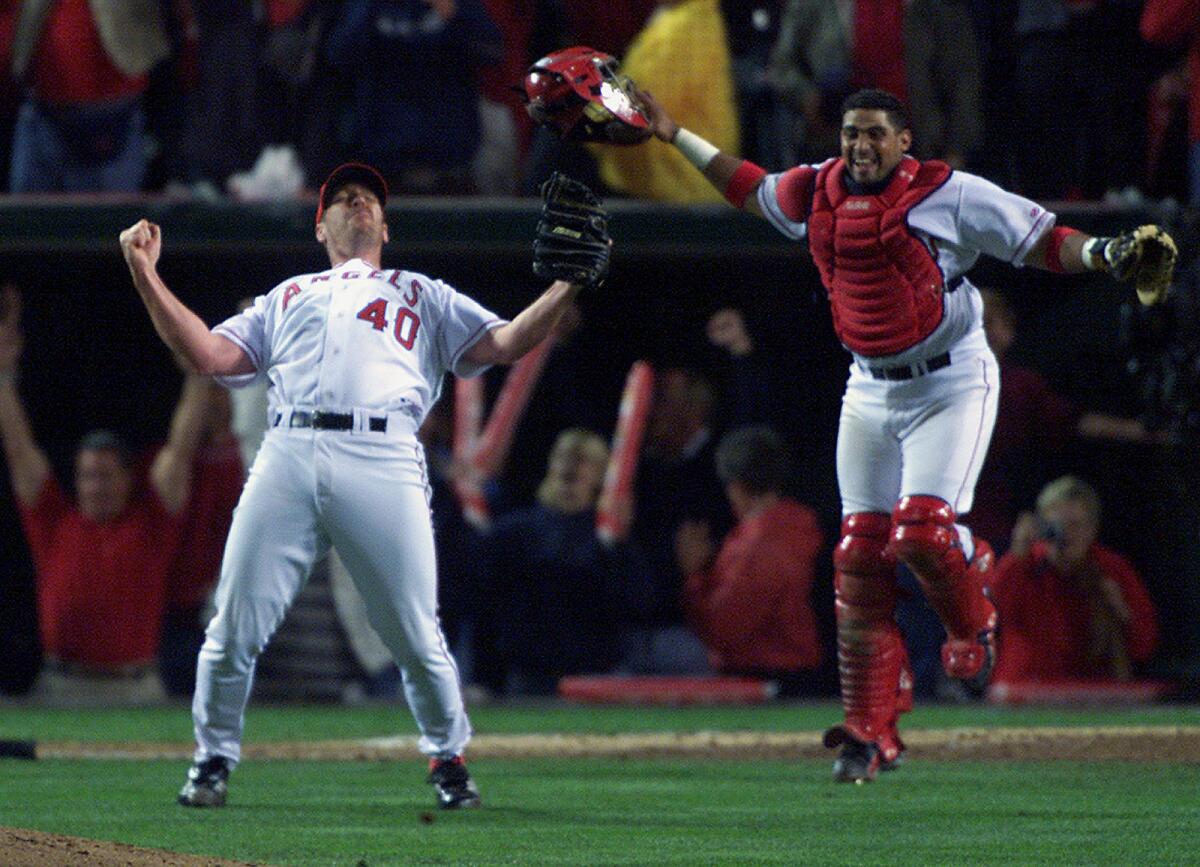

The Angels ascended to World Series immortality in Game 6 last fall, a magical game that forever defined a team, with an unprecedented comeback that cannot be compressed into a single image.

On that night, one hero would not be enough. On that night, when defeat would mean an empty end to a glorious season, the Angels spotted the San Francisco Giants five runs and 19 outs. In a century of World Series play, never had a team facing elimination overcome so large a deficit.

This was the stuff of lore, with center fielder Darin Erstad hitting a home run with a broken hand.

This was the stuff of human interest, with designated hitter Brad Fullmer knocking his high school teammate out of the game, with minor league nomad Brendan Donnelly earning the victory, with two brothers sharing the catcher’s mitt, with first baseman Scott Spiezio striving to win a championship ring just as his father had.

This was the stuff of fate, with the Giants throwing Erstad the only pitch he could possibly hit out and throwing Spiezio the only pitch he could possibly hit out.

In the same year Disney was looking to part ways with the Angels, the team put up its most memorable season, defeating the Giants in the 2002 World Series.

Without Spiezio’s home run, even the rally monkey might have left early to beat the traffic. With one swing, Spiezio ended the shutout, chopped the Giants’ lead to 5-3 and revived a dormant audience.

“That was far and away the biggest hit of our whole season,” Erstad said.

But the Angels still needed to take the lead and then preserve it, and Spiezio played no part in either. He happily acknowledges that, in that already legendary 6-5 victory, he was one hero among many.

“In Anaheim, it will always be one of those memories that people have, especially young kids,” he said. “They’ll grow up saying that team was incredible, to come back from 5-0 and have the whole team basically contribute to the comeback and then go on to win Game 7 for the first title in history.

“The great thing about it, the thing that I think everybody will remember from the World Series, is that the team beat the superstars. I think that’s what most of us are most proud of, the fact that we were a team and won it unselfishly.”

The Angels won Game 6, a game for the ages, with essential contributions from the well-known and the unknown on their roster. This is their story, in their words.

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Anaheim nine that night. The score stood four to nothing, and even Frankie, mighty Frankie, wasn’t right.

In the sixth inning, right fielder Tim Salmon wonders whether this sweet season will end within the hour.

Salmon made his major league debut in 1992, alongside teammates that included Bert Blyleven, Hubie Brooks and Junior Felix. He has played for four managers and four interim managers, but he has never worn another uniform. At the start of the postseason, he had played more regular-season games — 1,388 — without appearing in a playoff game than any active player.

Russ Ortiz, the San Francisco starter in Game 6, pitches splendidly through the first five innings, giving up nothing beyond a walk in the second and an infield single in the fourth. In the sixth, after a one-out single and two-out walk, the Angels finally have a runner in scoring position, with Salmon facing Ortiz.

Salmon: “I felt pretty good off him. He kept throwing me that cutter away, and I kept fouling it off. I felt confident, maybe overly confident. He had thrown me all those cutters away. All of a sudden, he threw me that cutter inside. It cut back over, and I took it for strike three. I was so mad at myself. I was crushed. I thought that was it.”

Salmon, left fielder Garret Anderson and closer Troy Percival all survived the short and painful collapse in 1995, when the Angels coughed up an 11-game lead in six weeks, and the long and painful years that followed. But all three spurned free agency, confident they could play for the Angels and play for a winner too.

While Salmon frets, Anderson and Percival refuse to believe the end is drawing near.

Anderson: “I’ve played too many games to think like that. As many times over the years as we’ve come from behind to beat people, I don’t think that way at all.”

Percival: “I’m always aware of the score, but I never think our team is out of it -- unless it’s 16-4 [the Game 5 score]. I thought we were out of that one.”

In the top of the seventh inning, Jeff Kent singles home the Giants’ fifth run, their second in two innings off the previously unhittable wonder child, Francisco Rodriguez. In the bottom of the seventh, Anderson leads off and grounds out. Third baseman Troy Glaus follows, with the Angels eight outs from elimination.

Glaus: “To be able to come back from the five down, probably 99% of the people out there thought we had no chance. But the 25 or 30 guys in our dugout thought we’d be all right.”

Glaus, the World Series most valuable player, hit three home runs in the Series, seven in the playoffs. This time, he singles.

Glaus: “I was trying to get something going so we could rally. You can’t hit a five-run home run, period. You can’t hit a three-run home run with nobody on base.”

Fullmer and Ortiz had played on the same team a decade earlier, at Montclair Prep in Van Nuys. In Game 2, Fullmer stole home against his high school teammate.

Fullmer singles, with Glaus taking second. As Fullmer exchanges handshakes with first base coach Alfredo Griffin, San Francisco Manager Dusty Baker walks to the mound and removes Ortiz.

Baker: “The Angels were the best big-inning team I saw last year. I watched the Angels against the Yankees. I watched the Angels against Minnesota. I took Russ out because I knew they were capable of a big inning, and they were starting to hit Russ pretty hard.”

Fullmer: “Personally, I think he should have stayed in. It might have been a different outcome. He didn’t have that high of a pitch count, and he was throwing the ball well.”

Ortiz had thrown 98 pitches. The San Francisco relievers that would follow -- Felix Rodriguez, Scott Eyre, Tim Worrell and Robb Nen — had given up two earned runs in 14 2/3 innings in the World Series.

Spiezio: “We knew he was getting far enough into the game that, if we could get something going, we could get him out of there. Even though their bullpen was great, we feel that we always have a chance if you get out the guy that’s dealing against you.”

Ortiz hands Baker the ball. Baker hands it back, as a memento of a job well done. Baseball protocol demands that game balls are awarded after the game, not during it. Several Angels, interpreting Baker’s gesture as a premature declaration of victory, are offended.

Baker: “That had nothing to do with the Angels and everything to do with Russ. I never thought the game was over at that point. That was a reward for Russ, for pitching a gem. If people needed that to get motivated in the World Series, they have a problem.”

Anderson: “It’s something you’ve got to understand about baseball teams and baseball players. When they see something different, out of the ordinary, that doesn’t fit within the context of how to play the game and the etiquette, you’re going to have some people that say some things. Personally, I didn’t care. It didn’t bother me in the least. He didn’t turn toward the dugout and look at us and hand him the ball.”

He did, however, fire up the Angel waiting in the on-deck circle.

Spiezio: “I remember everybody in the dugout going, ‘Did you see what happened?’ I remember thinking that was kind of a dumb move — well, not so much a dumb move, but a move that made us all mad. It made us think -- let’s do what we can to win this game.”

Ed Spiezio wears two championship rings, earned as a utility infielder for the St. Louis Cardinals. He batted once in the World Series in 1967, once in 1968. He did not want his son Scott similarly relegated to the bench, so he started training him to switch-hit -- at age 3. In the backyard of the family’s Illinois home, Ed made every batting practice session count, instructing his son to envision himself hitting in Game 7 of the World Series.

A lifetime of training for an imaginary Game 7 prepared Spiezio for the moment of a lifetime in Game 6. Spiezio takes a ball from Rodriguez, fouls off the next three pitches, takes another ball, fouls off another pitch, takes ball three.

Erstad: “In the moment, you’re not nervous. Looking back, it’s nerve-racking thinking about it.”

Every pitch is a fastball. Rodriguez trusts no other pitch. Every pitch is on the outside corner, or farther outside.

Glaus: “I remember standing on second base. I remember the pitch sequence. I kept waiting for him to miss middle-in so Spiezio could go deep.”

On his eighth pitch, Rodriguez misses. Spiezio pulls the ball, high in the air and down the right-field line. If Spiezio pulls one of the outside pitches, he pops up. If he hits this one anywhere except right down the line, where the fence is only 330 feet from home plate, he flies out.

Spiezio: “I knew I hit it on the barrel, on the real nice part of the bat, but I knew I hit underneath it. If anybody else were pitching, I probably would have thought it was an out. But with him throwing 97 mph, I thought there was a chance.”

Where are the 2002 Angels players and coaches now? Here’s what they are up to at last report.

Reggie Sanders retreats toward the right-field corner, with 45,000 hearts and 90,000 eyes tracking him. Sanders drifts back, and back, and back ...

Spiezio: “On the way to first, I was basically praying — come on, get out of here, God let this one leave. It seemed like half an hour. When I saw Sanders hit the wall, I knew it was gone.”

Shortstop David Eckstein: “No one got up off the bench until the ball actually cleared the fence. We were surprised the ball went out.”

Donnelly: “It just kept on flying. I was watching the outfielder. I saw him going back, and then I saw him hit the wall, and I said, oh

Spiezio: “It was one of those amazing moments where you feel like you’ve left your body. Your legs are running, and you don’t even feel them.”

Even now, on video replays, Spiezio holds his breath.

Spiezio: “It still makes me nervous, every time. I still think, go, go, as if it’s not going to go out this time.”

The Angels do not yet lead. But without that home run, they lose. And without that home run, perhaps Disney does not approve a $22-million payroll hike to keep the team largely intact, perhaps the Angels let Spiezio go, or trade Percival and anoint Rodriguez the closer. Baker might still manage in San Francisco; Kent and Ortiz and Sanders might still play there.

Salmon: “It’s that one play. If he hits it a foot shorter and it’s caught, how many lives are impacted by that? Everybody’s lives change, on our side and their side.”

Donnelly never gave up on baseball, although baseball gave up on him, more times than he cares to remember. He pitched for 14 minor league teams, two in the last-chance independent leagues. He worked odd jobs to pay rent, killing bugs and laying pipe and serving subpoenas. He earned his first major league victory last September, at age 31, and his second in Game 6.

As Glaus and Fullmer get on base, and as Spiezio homers, Donnelly watches from the bullpen, drenched in noise. He is coming in to pitch the top of the eighth inning, so excited that he finishes warming up as Glaus steps to bat.

Donnelly: “I was waiting while we scored the three runs. It didn’t matter if my arm was ready or not. The adrenaline just kicked in a little more.”

After Spiezio homers, Donnelly waits some more. Orlando Palmeiro, batting for catcher Bengie Molina, strikes out. The Giants replace Rodriguez with Eyre, and second baseman Adam Kennedy singles. The Giants replace Eyre with Tim Worrell, and Eckstein flies out.

As the Angels take the field in the eighth, the new pitcher is Donnelly and the new catcher is Jose Molina, Bengie’s younger brother. They are the first brothers to play catcher for the same major league team in the same season in 124 years, the first brothers to play for the same team in the World Series in 40 years. They are unsung heroes, not prodigies: Bengie bounced around the Angel minor league system for seven seasons, Jose bounced around two organizations over 10 seasons.

Jose Molina: “I started the season in triple A. I never thought I would be in Game 6 of the World Series and catching the last two innings. Inside, it makes me real proud. It makes me the happiest man.”

Molina, the rookie, must slow Donnelly, the rookie fueled by adrenaline, and later Percival, the veteran closer.

Molina: “I thought it was two hours, the last three innings. Everybody was hyper -- at least Donnelly and Percival were hyper. They were just, ‘Give me the ball.’ ”

Donnelly walks the Giants’ leadoff hitter, Benito Santiago. J.T. Snow flies out. Sanders strikes out. David Bell strikes out. The score holds. The Angels trail, 5-3, with six outs left.

As the Angels returned from the airport on the night of that 16-4 disaster, the team leader rallied his mates, roaring for all the bus to hear. If someone told you that you could win two games at home and win the World Series, Erstad demanded, wouldn’t you take that chance? Why couldn’t we win two more games?

His teammates did not know -- and, certainly, the Giants did not know -- that Erstad cringed in pain every time he swung a bat. Erstad did not know -- and did not learn until December -- that one of the bones at the base of his right hand was broken. He first felt the pain midway through the World Series, but he refused to surrender.

Eckstein: “He never complains about anything. He probably convinced his mind there was nothing wrong with his hand.”

Percival: “It was our time. He’s always going to rise to the occasion, hurt or not hurt. He’s always going to play -- concussions, whatever.”

Erstad leads off the bottom of the eighth, secretly hoping for a walk, not to avoid the pain but to avoid grounding out for the third time that night.

Erstad: “That’s probably the biggest at-bat ever, to get on base. I’m telling myself to take a strike, and maybe he’ll throw four balls.”

Worrell starts with a called strike. If he follows with a fastball, Erstad’s swing might not be strong enough to hit the ball with any authority. If he follows with a pitch on the outside half of the plate, Erstad might not be able to reach that far and hit the ball with any authority.

Worrell follows with a changeup, on the inside half of the plate. Broken hand and all, Erstad yanks the ball deep into the right-field pavilion.

Erstad: “Considering how I felt, I was pretty happy he threw me something I could catch up with. Them not knowing, that was the good part.”

Spiezio, to Erstad: “Wow. That’s amazing. You got that pitch and didn’t miss it.”

With six precious outs at their disposal, the Angels complete their comeback without spending a single one. After Erstad’s home run, the Giant lead that was once 5-0 is 5-4.

Salmon: “We had so much emotion after the home run. I really felt this was going to happen.”

As fans madly pound noise sticks above him, Chone Figgins runs alone, sprinting in the underground batting cages behind the Angel dugout. Figgins, the Angels’ designated pinch-runner, appeared in six playoff games, scoring four runs and batting once. From the sixth inning on, the rookie hustles impatiently between the dugout and the batting cages and back again, stretching, running, watching the game, waiting for his moment.

Salmon follows Erstad to the plate and singles. Figgins pops out of the dugout immediately, without waiting to hear whether Manager Mike Scioscia would order him to run for Salmon.

Figgins: “As soon as he got on, I was already on the field. Scioscia already told me that, if anybody gets on in the later innings, you’re going to be running. So I just went out there.”

Figgins represents the tying run, but he is not running -- not with Anderson, the Angels’ MVP, at the plate.

Anderson: “Worrell throws cutters that are conducive to hitting ground balls. I just wanted to make sure I kept the ball in the air. I didn’t want to kill the inning by hitting into a double play. I hit it in the air on purpose. I wasn’t trying to hit a blooper, but it just happened that way, and I kept it off the ground.”

Clubhouse workers scurry around the San Francisco clubhouse, yanking down the plastic sheets that would have protected lockers from champagne showers, hiding the stage on which the Giants would have received the championship trophy and Barry Bonds would have received the World Series MVP trophy. Bonds homered in Game 1, Game 2, Game 3 and Game 6, batting .500 in the first six games and reaching base 19 times.

His bat might have magical powers, his glove does not. Anderson bloops a single into left field, where Bonds stumbles upon the ball and bobbles it -- not once, but twice.

Figgins is not watching Bonds. He stops at second base, to the horror of his teammates.

Donnelly: “I was on the edge of the dugout, on the rail. And I was screaming at him, ‘Go! Go!’ Well, that wasn’t exactly what I was saying. But that was the tying run, and he held up.”

Figgins: “I didn’t see him fall until after I went downstairs and saw the replay. After I hit second, I picked up [third base coach Ron] Roenicke, and he was having me hold up, so I didn’t see that Bonds had fallen.”

Roenicke picks up Bonds, then waves frantically to Figgins. As Figgins races to third, Anderson alertly takes second, representing the go-ahead run.

Anderson: “When I first hit it, I was thinking two anyway, just because it was a blooper down the line. And then I saw Figgins go around the bag and I saw Bonds fumble. As an outfielder, once you fumble, you know a guy can take an extra base. So I just never stopped running.”

As Percival warms up for the ninth inning, the Giants desperately turn to their closer, with none out in the eighth. Nen, like Percival, pumps out fastballs at 95 mph, or more. But Nen’s shoulder is weak, and off-season surgery looms. The Giants try to keep the secret, ordering scoreboard operators at Pacific Bell Park not to display the speed of his pitches.

Glaus: “Because of what he throws -- a down cutter -- I was just trying to hit a ball on the ground, somewhere up the middle, so we could score one run, tie the ballgame up and go from there. If I moved the guy to third, even better. But fortunately he left it up.”

According to the scoreboard at Edison Field, Nen throws a 91-mph fastball. Glaus lines it deep to left field.

Percival: “I was in mid-pitch. I just heard it. I turned and saw him round first base.”

With the best of jumps, Bonds has a slim chance to catch the ball. But Bonds gets a clumsy jump, then thrusts his glove into the air, helpless as the ball sails over his head.

Glaus: “I saw him put his glove up, so I knew it was far enough, at least to be a sacrifice fly. He wasn’t going to be able to turn around and wheel and throw Figgins out at the plate. So at least that part of the job was done. When it got over his head, that was just gravy.”

Figgins scores, with Anderson right behind him, on the double by Glaus. With eight hits in 10 at-bats, with six men scoring once, the Angels incredibly and improbably lead, 6-5.

Erstad: “That was the epitome of what we were talking about all year — not doing it all in one shot, not hitting six solo home runs. We did it together. That was the whole lineup contributing, starting with Spiezio and ending with Glaus. It just defined our team really well.”

The three outs follow quickly. Fullmer strikes out. After the Giants walk Spiezio intentionally, Molina executes a sacrifice bunt. Kennedy strikes out.

The game enters the ninth inning. Percival enters the game, with the Edison Field decibel meter at record levels.

Molina: “We had the momentum. We just wanted to get strikes and outs. He did that pretty well. It was pretty much all fastballs.”

Tom Goodwin, batting for Shawon Dunston, strikes out.

Spiezio: “With a one-run lead, you’re usually not as comfortable as you are with a three-run lead going into the ninth, but that night I felt pretty comfortable, especially with Percival coming in. He’s wanted this his whole life. So, with that one-run lead, I had a lot of confidence we were going to Game 7.”

Kenny Lofton fouls out.

Erstad: “From the electricity from the fans to Percival coming on the hill, we were all so confident. In our minds, it’s over. He’s human, and he could make a mistake, but it just didn’t seem like it would be the right story if we wouldn’t have won that game after what happened.”

Rich Aurilia strikes out. Game 6 is won. Game 7 is on.

Molina: “I was so happy that day that I couldn’t sleep that night. I wanted to sleep, but I couldn’t until 3 or 4 in the morning. I couldn’t believe it. I turned on every TV station to see it. It was hard to believe it happened that way. I know it happened, but in your mind you ask yourself how it happened and how quick it happened.”

In the classic Game 6 of 1986, that ground ball trickled through Buckner’s legs, and the New York Mets won. Two days later, the Mets won Game 7.

In the classic Game 6 of 1975, Fisk waved his winning home run fair, and the Boston Red Sox won. The next day, the Red Sox lost Game 7.

The Angels win a classic Game 6, and with it perhaps the World Series.

Fullmer: “After Game 6, I knew we were going to win. Once we came back from that — they were two innings away from winning the World Series and we came back from five runs down -- that’s got to be a dagger. I don’t think there’s anyone on our side that didn’t think we were going to win. That had to be devastating. I don’t care who they have over there.”

Percival: “I didn’t think it was over, not with that team. You could see they could explode as well as we could at any time.”

Salmon: “Game 6 was really a great feeling. You really knew. You went home confident that we were going to win tomorrow. I wouldn’t say it was over, but there was a confidence, almost like it had already been decided. I just felt like the destiny thing was on our side.

“And then, on the other side, how crushed are they? They just blew a 5-0 lead. They were ready to pop champagne. All they needed was to win one game. They had the lead. They blew it. Now the pressure is on even more the next night — well, if five runs weren’t enough, we’ve got to score 10. You start to get into that mind-set, and I think that weighs on a team after they lose a tough one.”

The Angels win Game 7, with another cast of heroes. Bengie Molina doubles home the first run, Anderson doubles home three more, John Lackey becomes the first rookie in 93 years to start and win Game 7, and Erstad catches the final out of a 4-1 victory.

Glaus: “That was a great game too, and nobody ever remembers that. It’s funny. It’s just like the Red Sox, in Game 6 with Cincinnati. Nobody ever remembers there was a Game 7 after that. Buckner’s play in Game 6? Nobody remembers there was a Game 7 the next day. This was the same idea.”

Spiezio: “I had a lot of people tell me Game 7 was boring, but to me Game 7 was the most exciting. I’ll remember Erstad making the catch and Percival doing his patented pose and then not knowing what to do, just going kind of crazy and losing my mind for about five minutes. That’s a feeling you’ll never forget. It’s a totally different feeling than the home run, or anything else I’ve ever experienced.

“As a player, Game 7 was the highlight. But Game 6 was one of those moments that I think fans will remember, just because it was so intense.”

Kennedy: “For them, Game 6 was Game 7, the greatest game they’ve ever seen. They couldn’t believe we came back. It’s good to hear fans get into it like that.”

If the excitement was yours, the privilege was theirs.

Eckstein: “You don’t realize it while you’re playing in it, but afterward you see how it really went down. It’s an honor just to be part of it.”

Fullmer: “Years from now, it will be good to be a part of that and show the kids — when I have some.”

Anderson: “It’s fun to be included in history. To know we’ll be a part of that is pretty cool, from the standpoint of people always wanting to know what happened.”

Glaus: “We had a whole lot of fun being a part of it. I hope it goes down as one of those types of games that people talk about, where every young kid remembers the stories.”

Eckstein: “That’s the only game they talk about. From everybody that’s talked to me, that’s the game they want to talk about. Hardly anybody talks about Game 7. All they talk about is Game 6.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.