10 Years Later, Chicano Studies Are in the Mainstream

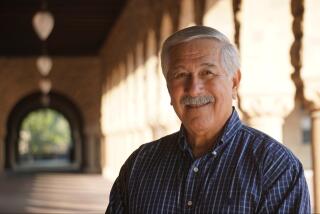

Adolfo Bermeo is leading a classroom of rapt UCLA undergraduates in a discussion of the 1980s civil war in Guatemala. âHave the issues that caused the unrest and upheaval,â he asks, â... those that caused the social fabric of the society to be tornâ gone away?

The historian and his students are talking about poverty and oppression far from their peaceful Westwood campus. But the question could just as well apply to their course in UCLAâs Chicana and Chicano Studies program.

In 1993, students and faculty members held a hunger strike to demand a Chicano studies department, a cause for which they said they were ready to die. Their protest drew national media attention and inspired demonstrations at other Los Angeles colleges and high schools. The strike was settled after 14 days, when the university agreed to create a Chicano studies center named for labor leader Cesar Chavez, upgrading a program from its status as a joint venture of faculty from other departments. The agreement gave Chicano studies the substance of a department without the name.

No one is starving for Chicano studies now. The Cesar E. Chavez Center for Interdisciplinary Instruction in Chicana and Chicano Studies has its own full-time faculty and control over its curriculum.

There are now 133 Chicano studies majors, up from 42 in 1993. There are 71 courses in Chicana and Chicano studies, compared with 28 in 1993.

âItâs a tremendous success story,â said the UCLA dean of social sciences, Scott L. Waugh, a key negotiator for the administration during the hunger strike.

The growing popularity has occurred without an increase in Chicano undergraduates. Chicano/Mexican American undergraduates make up about 11% of undergraduates, the same percentage as in the 1992-1993 school year.

Chicano studies emerged as an academic discipline in the late 1960s. Though centered on the study of Mexican Americans, the field increasingly covers other Latinos as well.

The nationâs first Chicano studies department opened at Cal State Northridge in 1969. In the UC system, only Santa Barbara has a Chicano studies department. Nationwide, 19 four-year institutions house Chicano studies departments.

Other ethnic studies programs at UCLA -- such as Asian American and African American studies -- remain interdepartmental programs staffed by professors from other departments.

UCLAâs Chicano studies program has seven full-time professors and is hiring two more. The faculty includes historians, linguists, artists and urban planners. Eighteen professors from other departments also teach courses there.

Course topics include musical aesthetics in Los Angeles; language politics and policies in the U.S., and U.S.-Mexico relations.

Among the arguments against creating the center in 1993 was a lack of student interest in Chicano studies, reflected in low enrollments and few majors. Also, administrators resented the hunger strike, saying the tactic was not the proper way to advocate academic changes.

Reynaldo F. Macias, a linguist who heads the Chavez Center, said it was necessary to have more substantial course offerings from full-time Chicano studies professors to attract more students and majors.

Now, the center has asked the UCLA academic senate for department status. Macias said the distinction is largely âperceptual,â because the center already controls its faculty and curriculum, and the change would not require additional funding.

Waugh supports the change, noting that there are more Chicano studies majors than there are students majoring in comparably sized existing departments, such as French, German and atmospheric sciences.

Waugh said he expects a smooth transition to departmental status, noting that other social science department heads support the change. Unlike the situation in 1993, âthereâs not any raging controversy,â he said.

Raul Hinojosa, a political economist and urban planning professor who teaches the U.S.-Mexico relations course, said the Chicano studies program has helped to keep him at UCLA despite job offers from schools such as MIT. Hinojosa said the âmultidisciplinary approach to teachingâ a Chicano studies course is especially satisfying. His U.S.-Mexico relations course, for instance, combines politics, economics and anthropology. âIn most schools ... in a political science department, there would be no way I could do this and be accepted within the department,â he said.

Bermeo, the historian, said that at UCLAâs Chicano studies program, he is âteaching future graduate students. Iâm preparing scholars.â

Some of Bermeoâs students described their studies as formative experiences.

âI didnât know what a Chicana wasâ before taking Chicano studies at UCLA, said Janet Gamboa, 18, a freshman political science major from Compton. Her immigrant parents, she said, emphasized her identity as âMexican.â

Through her courses in Chicano studies, she came to understand more fully that her experience of speaking English at school and Spanish at home, and of growing up in a largely segregated community, is an American experience. She now calls herself a Chicana, she said, because the term addresses âwhat we are here, as Americans.... The more I learn here, the less âotherâ I feel.â

Maria Shakelian, 20, a junior history major from Canoga Park, said that in Chicano studies courses she has found parallels to her own life as an Armenian American. âIf you didnât say âMexican,â you could be talking about my culture as well,â she said. âI realize from taking classes like this that you can understand someone from a different culture.â

Bermeo said such remarks reflect a shifting consciousness. Rather than encouraging separation, focused study of a single group like Chicanos helps students âtake ownership of our experienceâ as Americans.

Summing up the change he sees in his students, Bermeo might also be describing the evolving state of Chicano studies at UCLA, from protest subject to popular campus program. âTheyâre moving from the margin to the center,â he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.