Killer to Get Wish at Last: Death

Almost everyone at Robert Lee Massieâs execution early Tuesday will be there because they want to be, even Robert Lee Massie himself.

For more than 30 years, he has been saying on and off that he wants the death penalty rather than spending his life in prison.

But Massie--who killed in 1965 and again in 1979--has been kept alive again and again.

First there was the stay of execution by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan in the late 1960s, then the abolishment of the death penalty by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972, and finally a parole boardâs decision to set him free six years later.

It turned out that Massie was not done killing.

In all, he has been found guilty of murder and sentenced to die three separate times for the two murders. He has spent more years on San Quentin State Prisonâs death row than any other currently condemned man.

Barring a last-minute stay, he will be executed just after midnight.

âIâm tired,â the 59-year-old convict said in a telephone interview last week. âI just donât want to go on.â

The official record will show that Massie was executed for the 1979 murder of a liquor store clerk in San Francisco.

As Massieâs final day draws nearer, those whose lives he has hurt forever, those who just want him dead, go about their lives in nervous anticipation. Some are racked by flashbacks and nightmares.

At least eight plan to watch as Massie is led into a small prison chamber and injected with drugs that stop his lungs and heart.

Ron Weiss, whose mother was fatally shot by Massie in a Los Angeles suburb in 1965, will be there. So will the sons and daughters and adult grandchildren of Boris Naumoff, a San Francisco liquor store owner killed by Massie in 1979. Most of them say Massieâs death alone will not bring closure.

Still, the execution is wanted--is needed--they say, for a personal sense of justice. Separately, they describe their feelings in similar fashion:

This is my murder; it belongs to no one else but me. My father, my mother, would have wanted me to be there. Society couldnât keep this from happening; now society owes me this much.

âIf the guy who injects the poison is sick that day,â said Chuck Harris, whose thigh and life were permanently scarred by a Massie bullet, âI will do it. I will kill this man. Itâs been far too long.â

Following His Victims Home

On Jan. 7, 1965, Ron Weissâ parents were returning to their apartment in San Gabriel from their furniture business. Mildred and Morris Weiss didnât know their car was being followed.

They were pillars of their community, well-loved business people who had grown up near Central Avenue in Los Angeles and had raised two boys. Mildred was the outspoken one. Morris was quiet and reserved.

In the car trailing them was Massie, then 24, and another man.

Massie, who sported a gelled pompadour in the style of Elvis Presley, was a rebel rubbed raw by a childhood spent in foster homes and abusive orphanages in Virginia. From the age of 15 he had spent more time in jail than free. He drifted to California, bringing with him a penchant for taking his aggressions out on the innocent.

Massie had just robbed a West Covina man on the victimâs front lawn. He had taken $2.93 and fired his .22-caliber handgun. A bullet grazed his victimâs temple.

When the Weisses arrived home, they didnât stand a chance. Massie bounded from the darkness, pointed his gun at Mildred Weiss as she got out of the car and demanded money.

Perhaps because she resisted, perhaps because he suddenly saw Morris getting out of the car, Massie shot Mildred in the stomach. The bullet sliced her aorta.

Ron Weiss, now 54 and a successful businessman, was 18 then. He was in the apartment watching TV when Massieâs gun went off. When he heard his father cry for help, he ran outside. Weiss and his father then chased Massie down the block before Massie jumped into his getaway car and fled.

âThere has been nothing worse than the image I have of my mom that night,â said Weiss, who keeps a box of the clothes his 48-year-old mother was wearing when she was shot tucked away in a closet. âI can see it, so clearly, even now. She was so strong, still talking even as the paramedics were working on her. She didnât deserve this.â

In the first weeks of 1965--as President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed Congress and outlined his âGreat Societyâ plan, as Winston Churchill withered on his deathbed, as Jerry West pushed the Lakers to a string of victories--Los Angeles media were riveted by the search for Mildred Weissâ killer.

Massie was arrested about a week after the Weiss shooting by two plainclothes officers in downtown Los Angeles. During questioning, he gushed to them that he had killed Weiss, and he said he would have shot Ron Weiss and his father if his gun hadnât run out of cartridges.

Massie pleaded guilty. The judge sentenced him to death.

By October 1967 Massie was on death row at San Quentin. He was so close to being executed that he had ordered his last meal, arranged for a chaplain to provide spiritual support, and even made a will.

Then, Gov. Reagan intervened, ordering a stay and demanding that Massie testify in the case of Robert Vetter, the man implicated as his getaway driver.

Though Massie shot back a letter to Reagan telling him he didnât want a stay, the convicted killer was sent to Los Angeles to testify.

He told the court that Vetter was not with him during the crime spree. He said the getaway driver was someone named âSmitty,â a man he met that night and had not seen since.

Vetter was freed. Massie went back to death row.

Within days the California Supreme Court, grappling with the death penalty, suspended all executions indefinitely.

By 1970 Massie had become a well-known member of San Quentinâs death row. He had repeatedly stated that he wanted to be one of the first to die after executions resumed. He had schooled himself in case law and was savvy about using the media to make his points.

Truman Capote wrote about him. Newspapers called him âThe Killer who Wants to Die.â

In 1971 Massie wrote a revealing article for Esquire magazine. He assailed the death penalty as anti-Christian and politically motivated, called lifetime imprisonment torture, and said most publicly funded death penalty defense attorneys railroaded their clients.

But Massie also made it abundantly clear that he agreed with the mandate to kill him.

âKnowing that I am going to die, why should I be made to suffer further years of confinement?â he wrote. âThe law is clear, and I have every right to demand immediate execution.â

When the U.S. Supreme Court put an official end to executions in 1972, Massie became part of a group of death row inmates whose sentences were changed to life with the possibility of parole.

Soon the state parole board was reviewing Massieâs case. In 1978 it looked at reports from prison officials stating that Massie was a model prisoner. Board members heard from a Catholic priest vouching for his good character and from psychiatrists touting Massieâs âbehavior and character changes.â

âI wish you guys would let me out,â Massie told the board. âI am ready to leave. I am tired of prison, I am tired of crime. I just want to start to build a future for myself.â

The parole board set Massie free in the summer of 1978.

On Jan. 3, 1979, he walked into Miraloma Liquor, a tiny store in San Franciscoâs Twin Peaks neighborhood, carrying a gun. He robbed the owner, 61-year-old Boris Naumoff. The two fought, and Massie whipped out his gun and shot Naumoff three times in the chest. Other bullets careened through the narrow store. One hit store clerk Chuck Harris.

Days after killing Naumoff, Massie was caught in San Franciscoâs Haight-Ashbury district. He sat down with police, looking wired, ashen and weary of the world. He asked for a sandwich, then he confessed.

The court proceedings moved swiftly. When the judge ruled that he couldnât have his confession expunged, Massie pleaded guilty against the advice of his lawyer. Now a twice-convicted killer, he went back to death row.

He was there six years when, in 1985, the California Supreme Court decided there was a significant flaw in his case. The high court, pressured in all death penalty cases to ensure that verdicts pass the intense scrutiny of federal appeals, concluded that Massie should not have been allowed to oppose his lawyer by pleading guilty. The court, under then-Chief Justice Rose Elizabeth Bird, ordered him tried again.

In 1989, for the third time in his life, a court found Massie guilty of murder.

In recent years, Massie has spent much of his time criticizing the automatic appeals process in California capital cases. He has long held that capital defendants, provided they are found mentally competent, should have the right to forgo appeals.

Massie and his lawyer have argued that his 1989 retrial was a violation of constitutional rights against being tried twice for the same crime, and therefore he should be set free.

The California high court never gave the argument much credence. After state-mandated appeals were exhausted, the case moved to federal court.

When Massieâs stance was rejected once more, he went back to preferring death over prison.

Two months ago, a judge allowed Massie to drop all further proceedings at the federal level. His fate was sealed, pending the flurry of last-minute appeals underway by death penalty opponents.

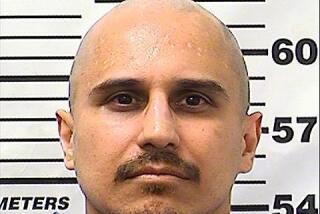

Massie, a slight, brown-haired man with a pale luminescence to his skin, spends much of his time in his cell, which is lined with law books and case files. He types letters, makes calls, sees a few visitors, and seethes at the death penalty protesters who would prolong his imprisonment.

To this day, Massie claims that his victims brought their fates on themselves. Among his views: The liquor store tragedy wasnât a robbery, but a dispute over change. If Boris Naumoff hadnât attacked him, Naumoff might still be living. Mildred Weiss actually pushed his gun into her stomach.

âI know,â he said, âit is hard to believe.â

Massie says Harris, outspoken in his desire to see him die, has âblood lust.â

âWhat he doesnât realize is I could have put a bullet in his chest or his eyes,â Massie said. âI hit what I point at. I put one in his leg to stop him.â

Still, Massie is a man of contradiction. There is sometimes sorrow in his voice. A devotee of Eastern religious traditions, he says he has spent a great deal of time thinking about his victims.

âI have looked back on some of the stupid things that have happened in my life . . . with profound regret,â he said. âI have actually gone into deep meditation at times, trying to let the departed spirits know how I really feel. I wish I could have lived my life differently.â

He will be the 420th person executed at San Quentin. He will be the ninth person put to death since California resumed executions in 1992, after a 25-year hiatus.

âI try to distance myself from the [execution] quite a bit,â he contends, speaking in a soft Southern drawl. âI realize they will do what they have got to do. Meantime I try to maintain my equilibrium, my poise inside. I go about my daily existence.â

Again, a Claim That Massie Is Not Violent

At the execution, one of the few witnesses friendly with Massie will be Frederick Baker. Although Baker normally represents corporate clients, he has been Massieâs lawyer for the last nine years and the two men have become close.

âHeâs a mature, frail man,â Baker said. âHe is a much, much different person than he was years ago. I have seen nothing to indicate he is a violent man anymore.â

But the families and Harris think something far different. Ron Weiss grieves not only for his mother, but for his father, who died two years ago at 83.

In his final years, Morris Weiss kept his feelings about his wifeâs murder deep inside. He retired and remarried. He volunteered as a clerk for the Los Angeles Police Department. He hoped to live long enough to see Massie executed.

Ron Weissâ eyes tense with anger and sadness when he thinks of 1965: his mother on a gurney and in a pool of blood, Massie laughing and smirking at him during the trial.

The murder made Weiss an extremely cautious man. He incessantly checks his doors to make sure they are locked. He works to be aware of everyone and everything around him. As he drives, he watches to see if someone is following him home.

âHe has never, not once, expressed remorse for this,â said Weiss, tapping a file of old newspaper clippings. âI have no problems with him being put to death. I only wish my father was here.â

Diane Salem, 57, is the oldest of Boris and Lucille Naumoffâs four children. She is retired now and close to her fatherâs age when he was murdered.

Knowing Massie is getting what he wants bothers her.

âI know he wants to die,â Salem said. âIt makes me think, if he wants out of the suffering, well, maybe we shouldnât kill him. Maybe he should just be left to suffer.â

The execution conjures up painful memories of both parents. On the day Boris Naumoff was shot to death, before the tragedy, Lucille Naumoff went to a doctor with stomach pain. She was diagnosed with cancer. She would die within eight months, hardly fighting as she grieved for her husband.

Boris and Lucille Naumoff missed seeing Salem have a successful career at General Electric. They never got to visit her handsome new home in a Sacramento suburb. They missed seeing Salemâs son grow up. She cries at the thought of this.

For Chuck Harris, who works at a grocery store near Miraloma Liquor, the Naumoff murder plays over and over in his head.

At 58, he still sees Massieâs piercing eyes, feels the sharp burn of the bullet that smacked him in the leg, and hears Naumoffâs last, rattling breath.

Sometimes, in the dead of night, Harris roams the streets of San Francisco, unable to sleep, haunted by memories.

âFor the families, for the people who have waited, this is something personal,â Harris said. âThe bad guy is gonna die.â

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.