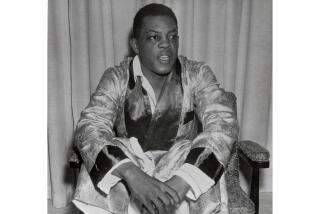

Ralph Bunche Spent a Lifetime Battling Bias, Seeking Peace

- Share via

In the Los Angeles that existed before the civil rights movement, a black high school valedictorian from Watts was denied membership in a city honor society because of his race. More than a quarter-century later, he would return to the city of his youth as the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

In the pantheon of world heroes, Ralph Johnson Bunche was the first person of color honored with the award that would later go to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. The agreement Bunche crafted to bring Israelis and Arabs together would be used 42 years later as a model for the truce between two Los Angeles gangs, the Bloods and Crips.

Yet, only three decades after his death, Bunche’s name is rarely invoked and his career as a peacemaker is nearly forgotten.

A man of determination, Bunche spent a lifetime bridging racial barriers and using his skills as a peacemaker to instill in others the same hopefulness that carried him through his celebrated career--and its difficult beginnings.

Born the grandson of a slave and orphaned at 12, Bunche rose to become the undersecretary general of the United Nations, the organization’s second most powerful official.

Bunche was not yet a teenager when he came to Los Angeles from Albuquerque, shortly after World War I. He lived with his maternal grandmother, Lucy Taylor Johnson. From an unpretentious frame house at 1221 E. 40th Place, he walked to classes at John Adams Middle School and then Jefferson High School.

Bunche hit the books with a vengeance in high school, earning the highest grades in the Class of 1922. All the while, he worked as a “pig boy” at the Los Angeles Times; his job was carrying the lead ingots called “pigs” to the Linotype machines in the composing room, where the lead was melted down and set into type.

But he was denied membership in the Ephebians, a citywide honor society. Eight years later, the honor would finally go to a black student: future Mayor Tom Bradley.

In his bitterness, Bunche considered dropping out of school. “I was aimless, for there was no strong incentive for a black youth . . . to make the long and supposedly formidable sacrifices necessary to acquire a higher education,” Bunche later said in a speech at UCLA.

Standing in the way of his dropping out was his very wise and determined grandmother, a woman of such light skin that she was often mistaken for white.

“She never raised her voice, but was very strong. . . . As white as she was on the outside, she was all black pride and fervor inside,” he said.

Bunche stayed the course and graduated, accepting a football scholarship to UCLA. That summer of 1922, between high school and college, he worked as a carpet layer and at night he cruised Central Avenue in his jalopy, all the while “fired by bathtub gin and apple brandy,” wrote his biographer, Brian Urquhart.

At UCLA--the Vermont campus where Los Angeles City College now stands--he supported himself by working at Campbell’s Bookstore across the street, as a janitor in the women’s gym and as a houseboy for silent screen star Charles Ray.

Yet he still found time to date, write articles for the Daily Bruin newspaper and excel in a black debating group, which he and some friends organized after the school’s official debating society--the white one--turned them away.

Bunche was no stranger to conflict and controversy, even as an undergraduate. Turning the color of his skin into a badge of pride, he spoke out at a community meeting about blacks’ being banned from a Venice swimming pool:

“Any Los Angeles Negro who would go bathing in that dirty hole with that sign ‘For Colored Only’ gawking down at him in insolent mockery of his race is either a fool or a traitor to his kind.”

While he quarterbacked for the debate team, he was equally motivated on the football field, until an injury left him with a blood clot in his leg that would plague him for the rest of his life.

In 1927, the nation’s first black political science major graduated as UCLA’s first black valedictorian. Pursuing a master’s degree and later a doctorate at Harvard, then teaching at Howard University, Bunche soon found that life’s rewards weren’t confined to sports or scholarships. He became enamored of a student, Ruth Ethel Harris, and they married in 1930.

Always eager for knowledge and new experiences, he soon became part of a group of young, black radical intellectuals at Howard. He protested the staging of “Porgy and Bess,” challenged government officials on policy toward minorities and volunteered his time to W.E.B. DuBois, the dean of black intellectuals. DuBois wrote back, saying there were no openings but he’d “keep [him] in mind.”

It was only recently learned that, in the late 1930s, Bunche crafted the first draft of Swedish social economist Gunnar Myrdal’s landmark study of American blacks, “An American Dilemma,” for which Myrdal would later receive a Nobel prize.

Bunche’s academic career was soon overtaken by a growing civil rights activism that carried him into the Office of Strategic Services--the forerunner of the CIA--during World War II, then to the State Department and ultimately to a role in helping to found the United Nations.

In 1948, after he was appointed the U.N. secretary general’s personal representative, his boss, the Swedish diplomat and mediator Count Folke Bernadotte, was machine-gunned to death by three members of the Jewish terrorist Stern Gang. A chance delay of his plane kept Bunche from joining Bernadotte, sparing his life.

And so it fell to Bunche to undertake the negotiation of a truce between the new state of Israel and its Arab enemies.

He pioneered “shuttle diplomacy” and engineered at least a brief peace in 1949. The next year, he learned that he was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, winning over such contenders as Winston Churchill, Harry S. Truman, Albert Schweitzer and George C. Marshall.

Bunche declined the honor, saying “peacemaking at the U.N. was not done for prizes.” Not until his bosses insisted that he accept it as a tribute to the fledgling U.N. did he agree to do so.

Bunche stayed at the U.N. and was promoted to undersecretary general, brokering accords in the Middle East during the Suez crisis and the Six-Day War, but also in Lebanon, Cyprus, Yemen and the Congo. On his trips, he answered letters from discouraged young people, encouraging them to pursue a more just society--starting with an education.

His achievements were made at great personal cost. A heavy smoker, he suffered from diabetes and hypertension. But health was not the reason when, in 1953, he turned down Truman’s offer to become assistant secretary of state. Bunche said he would not work in the nation’s still-segregated capital.

Ultimately he would receive 69 honorary degrees and become director of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People before he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963. Two years later, he joined King in the aborted Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” after marchers were attacked by police.

In 1969, Bunche returned to Los Angeles for the dedication of Ralph Bunche Hall at the new Westwood campus of UCLA. It stands in marked contrast to Bunche’s boarded-up and graffiti-marred boyhood home, a listed cultural and historic landmark that sits waiting for rehabilitation. That is scheduled to begin in March; it will become a museum to keep his memory alive. He died two years later, at age 67.

UCLA’s Center for African American Studies will hold a free premiere screening of the new documentary film “Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey,” at the Anderson School’s Korn Convocation Hall at 7 p.m. Monday. Reservations must be made by calling (310) 206-3535. The documentary will air nationally on PBS on Friday.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.