Homework Moves Into the Video Age

- Share via

WESTMINSTER, Colo. — Fourth-grader Jon Nooning is on a video game adventure. His fingers fly as he maneuvers an animated character into a rock canyon and begins knocking down walls with a pingpong ball.

He’s focused, excited and striving to get to a higher level of the game. Video designers would say Jon is “in the flow,” in a heightened state of creativity where all else is blocked out and a player’s only focus is on the television set before him and on winning the game.

But, in this game, Jon doesn’t have to kill anyone or rescue a princess before he reaches his objective. All he has to do is conjugate several verbs correctly and he can move on to the next level, where the verbs are even more difficult.

He’s not just playing a video game; he’s doing his homework.

“You can play a game and learn at the same time,” Jon said as he demonstrated how to use his school’s latest gadgetry. “It makes learning a lot more fun.”

The 9-year-old pupil at Flynn Elementary School is one of thousands of children at 600 schools in 40 states who are participating in a study aimed at weighing the effects of video games on student achievement.

The three-year study, conducted by San Diego-based Lightspan Partnership Inc., a software company, is backed by $100 million, and its investors include Microsoft Corp. and Tele-Communications Inc.

At the beginning of the school year, each family involved was given a $149 Sony PlayStation, a video game console that plays compact discs. Every week, teachers assign a video game CD for homework.

Videos feature 3-D animation, live-action video and cartoon characters such as Quaddle the toucan, who leads students through a curriculum that includes math, reading and language arts.

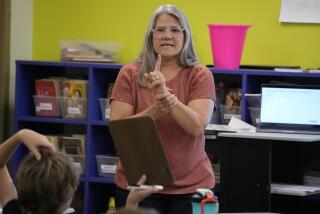

Rhonda Kobi, who coordinates the Lightspan program for the Flynn school, said she and other teachers introduce lessons in class before students are given a video game to take home. The goal is to extend the classroom day at home and to encourage parents’ participation.

“As a teacher, I see it as a reinforcement of what I’m teaching in the classroom,” she said. “I can see a big difference. Kids are excited. They’re always asking, ‘When do we get the new one?’ ”

Lightspan spokesman Bob Greene said preliminary results based on 25 schools and more than 195 families who used the games last year indicate parents have become more involved with their children’s homework and students are more motivated.

“We know kids like to watch TV and they like video games. If we’re going to get them to do math and reading at home, they are going to have to want to do it,” Greene said.

The homework software is as high-tech and flashy as the best-selling video games, but all that technology doesn’t mean anything if the games don’t measure up to the standards of teachers and parents, Greene said.

Jon’s mother, Tami Nooning, who sits on a parental advisory committee at the Flynn school, dismisses criticism that the video games will encourage children to spend more time in front of the TV and less time opening books.

“I do not see this as a drawback. I’d just as soon they sit down to Lightspan than to ‘Rugrats’ or Bart Simpson,” she said.

Fourth-grader Sarah Heasty, 9, said she is watching less television now that she can play video homework games.

And, she said, “We’re learning about nouns and adjectives.”