‘They Took My Son From Me’

- Share via

The Martinez family had returned to a Florence neighborhood to retrieve their broken-down car. They simply wanted to avoid a parking ticket. Instead, they wandered into a war zone, caught in a barrage of bullets from an AK-47 assault rifle.

When it was over, Hector Martinez, a 9-year-old boy with a passion for music and soccer, tumbled out of the car bleeding, holding his head in his hands. His mother and father lay wounded, and their 6-year-old son had been hit in the knee.

David Martinez, a 32-year-old mechanic, scrambled to save his children as gasoline leaked from his bullet-riddled car.

A quiet summer evening on East 61st Street, which only moments earlier had been alive with playful children and chattering adults, had been suddenly transformed into a scene of unspeakable chaos and violence.

Three days later, late Wednesday night, Hector died at Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center, one gunshot wound in his head, another in his back.

“They took my son from me,” a shaken and grieving Alejandra Murillo, 25, said Friday. “My son was innocent. He was my everything.” No one on East 61st Street understands why the gang members opened fire on a car with four children in the back seat. The gang members were shooting “stupidly” one witness said in Spanish, “a lo tonto.”

As the family prepared Friday to bury Hector, his brother Christian, 6, was recovering from injuries to his knee. The boys’ parents were recovering from leg and chest wounds. Only Kimberly, 4, and Brian, 3, escaped injury.

Why had it happened? The only official explanation came in the dry language of a Sheriff’s Department news release, read by Deputy Benita Nichol:

“We believe that the victims were possibly caught in the cross-fire of a rival gang that was shooting at Florencia street gang members who were inside the apartment building.”

Those close to the Martinez family could only bow their heads in sadness, unable to make sense of the cruel fate of life in the city. The Martinezes had lost a smart and beautiful child simply because their paths collided with a group of faceless killers on a darkened street.

The Martinezes had fled Los Angeles a few years ago, seeking to escape the unpredictability of urban violence. In Buena Park, Hector had taken up the accordion and enjoyed playing soccer in his new suburban neighborhood.

“I wanted them to be safe,” said Murillo, a gaunt woman with dark circles under her eyes after a week of sorrow. She still wore her hospital bracelet, days after being treated. And she lifted the corner of her blouse to reveal her bullet wound, a circle of bruised flesh and a very fine cut, as if from a razor blade.

Talking of her son’s musical talents, she doubled over in pain. “He was my adoration,” she said.

Christian, his knee still bandaged from the shooting, played nearby with a video game.

The series of events that would lead to Hector’s death began two weeks earlier, when the family returned to the Florence neighborhood, apparently to visit friends. Their car broke down in front of a white stucco apartment building that is a hangout for the Florencia 13 gang, according to Sheriff’s Department officials. Residents said the Martinezes had friends in the building.

Worried that his car would be ticketed because a sign indicated that a street sweeper would soon pass, David Martinez and his family returned to the neighborhood to move the stranded vehicle. They were struggling to make ends meet, and he couldn’t afford a citation. His wife, he had figured, could drive the children home in their good car. Maybe he could fix the bad one and drive it home. At the very least he would move it to a safe spot.

Sixty-First Street intersects with Central Avenue in a neighborhood where even the palm trees are spray-painted blue with the “F13” graffiti of the local gang.

Like many others in the poor communities south of downtown, the block is a study in contrasts: nicely kept single-family homes next to ramshackle ones, apartments that menacing gang members claim as territory next to apartments where young children play.

On the night of the shooting, a large group of children and adults were gathered on the sidewalk and the stairs of the apartment building, trying to escape the heat after a sizzling day, witnesses said. One resident said there were about 20 people on the street, “kids, old people, everyone.” The Martinez family pulled up in their 1976 Ford Granada, parking in front about 9 p.m.

David Martinez stepped out of the car, leaving his wife in the front seat. Hector, his two brothers and his sister sat in the back.

At that moment, a car passed slowly on 61st Street. Someone inside opened fire.

The windows in Martinez’s car shattered, and David Martinez fell to the ground. The attackers drove half a block and opened fire on the car again, witnesses said.

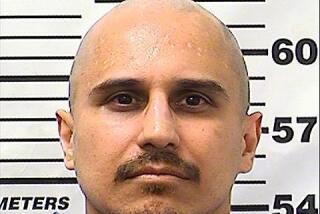

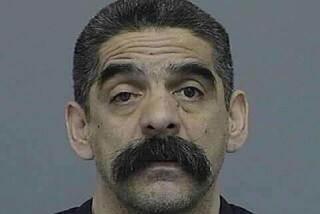

“They were blasting,” said Anthony De la Cruz, 22, who identified himself as a member of the Florencia 13 gang. De la Cruz said he believed that he, his brother Mario and some other young men were the intended targets.

“They were tying to get us,” said Mario, an 18-year-old with a shaved head and abundant tattoos. Both Mario and his brother shrugged when asked why they would be attacked.

“It’s gang-related,” Anthony said, as if that explained everything.

Later the two young men helped arrange a makeshift sidewalk shrine around a small statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe. When he was done, Mario counted the votive candles: There were 22.

By Friday, a new graffito had appeared on the concrete curb, the letters in black, the color of mourning: Hector R.I.P.

Authorities said they found six shell casings from an AK-47 scattered about the crime scene. Witnesses said the attackers also fired a .22-caliber handgun and other weapons. No arrests have been made.

Hector was rushed to the hospital with wounds to his head and back, family members said. He was still conscious, even after surgery, and was able to talk to his parents. The family was told he would recover and be released in five days, said Mercedes Lubiano, the boy’s aunt.

“What we don’t understand is why the doctors would tell us he would be OK,” Lubiano said. It was only when the family returned home after a long vigil at the hospital that they received the call informing them that Hector had slipped into a coma.

Sheriff’s officials say there have been 68 gang-related homicides this year in the communities they patrol. The Los Angeles Police Department has reported 83 gang-related homicides. Just two weeks ago, an 18-year-old gang member was gunned down in Florence, on 66th Street, about seven blocks from the site of the attack on the Martinez family.

Family friends and neighbors in Buena Park said the parents were too grief-stricken to return to their apartment on Kingman Avenue. They were staying with nearby relatives.

“They don’t want to come here,” said neighbor Nancy Pedroza. “They feel depressed knowing their son isn’t going to be here.

Javier Garcia, 9, was one of Hector’s many playmates. “He was in a music class,” Javier said. “He got a scholarship for music.”

The two boys used to play soccer together. “Over there,” he said, pointing to a patch of lawn on the quiet street.

The boy’s parents are natives of Mexico City and have lived in Southern California about a decade. Relatives said they were trying to raise money to transport Hector’s body back to Mexico for burial.

Alejandra Murillo spent Friday at her in-laws’ apartment, surrounded by her three children and pictures of Hector.

When his mother cried, Christian stood and put his hand on her shoulder, and was soon joined at her side by his sister Kimberly.

“The children are innocent,” Murillo said. “The children aren’t to blame.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.