New Transplant Technique Extends Boyâs Life

UPPER ST. CLAIR, Pa. â Eleven-year-old Mike Eisenbeis remembers little of life without leukemia.

Diagnosed at 4, he lost his hair four times in seven years and never made it through a single year of school uninterrupted.

Mike was so riddled with leukemia by last summer that most doctors would not have attempted a transplant that he had a 1-in-20 chance of surviving.

âWe had less than no hope. Heâd had so much radiation and so much chemotherapy,â said Ginger Eisenbeis, Mikeâs mother. âNobody would have touched him. Another center would not touch him.â

Fortunately for Mike, Steven Neudorf, the chief of bone marrow transplantation at Childrenâs Hospital of Pittsburgh, had just adopted a new technique for transplants--combining an extra dose of radiation with a manipulation of disease-fighting cells in the marrow.

The Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston had tried the extra radiation on adults. Neudorf wanted to reduce the dose for a test on children in full relapse.

The decision was painful for Ginger Eisenbeis.

Just three months earlier, Mike had been through a cranial-spinal radiation treatment that threatened to cause severe brain swelling. Instead, the radiation produced bleeding sores in his mouth.

âI didnât want to do the transplant,â she said. âI just thought, âGod, if youâre going to heal him, do it without the transplant.â â

But without it, doctors told her, Mike could die within a month.

Doctors usually start treating acute lymphatic leukemia with chemotherapy, which cures 60% of patients. The next step for those not cured is a bone marrow transplant.

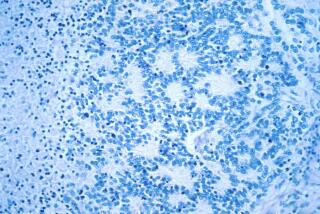

Neudorfâs technique involves T cells, disease-fighting white blood cells found throughout the body. In transplants, the cells can cause the patient to reject the bone marrow or to develop a fever and rash.

To prevent rejection, doctors use chemotherapy and radiation before the transplant to suppress a patientâs T cells. Neudorf added an extra dose of radiation to the lymph system, where the T cells are produced.

Other U.S. medical centers have shied away from the extra dose because no one has proven that its effects outweigh its toxicity, said Lisa Getzendaner, a physicianâs assistant for the unrelated donor program at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

To fight the chance of a fever and rash, a condition that kills almost half of all patients who get marrow from an unrelated donor, doctors until recently killed all the T cells in the donorâs marrow. But now they realize that a few should be left behind to kill any remaining leukemia cells and even to help prevent rejection.

The trick is getting the formula right.

With Mike, Neudorf zapped 93% of the T cells in the donorâs marrow. The remaining 7% did cause mild sickness, but the cells appear to have wiped out any trace of leukemia.

âYou get addicted to crisis and bad news,â Ginger Eisenbeis said. âThen, when I got the good news, I was in shock. Youâre so used to saying âNo hope.â â

Dr. Marshall Lichtman, the executive vice president for research and medical programs with the Leukemia Society of America, said he would reserve comment on Neudorfâs technique pending further study.

Getzendaner said Mike needs to be free of leukemia for about two years before doctors can be confident that he is cured.

Neudorf agreed that he needs to treat more patients before he can call his technique a success.

âHereâs a boy who would be dead now,â said Neudorf. âIf we do 15 patients like Michael, and theyâre all doing well 10 months after transplant, this has the potential to change the way people do transplants around the country.â

If nothing else, the transplant has bought Mike more time.

âI was amazed,â Mike said. âIâve gone through so much. Iâve relapsed and relapsed and relapsed, and all of a sudden--poof!--itâs gone.â

Heâs excited about spending all of sixth grade in school, playing baseball for a full season and getting a dog.

Mike said he never stopped thinking about his future. He spends much of his free time constructing the 3-D puzzles and bright plastic building sets that pepper his living room, and he talks of becoming an architect.

âI just feel so blessed amongst all the horror,â Ginger Eisenbeis said. âI know in my heart God has given him a purpose.â