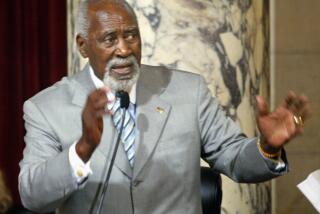

Commerce Chief’s Links to AT&T; Partner Questioned : Ethics: Brown didn’t disclose Kellee Communications’ ties to giant firm, which benefited from his Saudi efforts.

- Share via

Early in 1993, when Ronald H. Brown’s nomination to be commerce secretary was pending before the Senate, he filed a lengthy financial disclosure statement that reported ownership of shares in a relatively small firm called Kellee Communications Inc.

What Brown did not disclose was that most of Kellee Communications’ income came from a contract to operate pay telephones at Los Angeles International Airport--in a multimillion-dollar joint venture with AT&T;, which had important financial interests pending at the Commerce Department.

Five months after his confirmation, Brown--while retaining his investment in Kellee--traveled to Saudi Arabia to initiate talks that eventually produced a $4-billion contract for AT&T; to provide a modern telephone system for that country. The trip was one of several actions that the secretary and his department have taken that have benefited the communications giant.

Brown’s handling of the Kellee investment fits a pattern in which he has retained extensive financial interests while in government service but appears repeatedly to have sidestepped federal ethics rules that call for complete disclosure of an official’s financial affairs as a safeguard against possible conflicts of interest.

Moreover, by refusing to answer questions about his affairs and by insisting on secrecy and limited disclosure, Brown has added fuel to the controversy.

Brown, whose private business activities are now the subject of a congressional investigation and other inquiries, has repeatedly denied any impropriety.

But his connection to AT&T;, which was discovered during a Times examination of his business holdings, appears to run counter to the pledge Brown made when nominated by President Clinton that he would avoid even the slightest appearance of conflict between his official duties and his personal business interests.

“The American public needs and deserves absolute certainty about whose interests are being served in government,” he told the Senate Commerce Committee during his confirmation hearings in January, 1993.

Brown seemed to recognize a potential conflict inherent in the Kellee situation, however. He included that investment--with an apparent value of about $50,000, although he has refused to answer any questions on it--in a group of others that he told the committee he would ask Clinton Administration ethics experts to scrutinize and issue a waiver for, thereby enabling him to retain ownership of the stock.

But instead of seeking the waiver, Brown gave the stock to his son without publicly disclosing how he had disposed of it. The timing and nature of the transfer remain unclear because Brown refuses to discuss it, but apparently no money changed hands, and critics question whether it was an arms-length transaction.

Among the many questions that remain about Brown’s investment in Kellee are these: How much, if any, of his own money did Brown put up for his Kellee stock? How profitable has the link to AT&T; been to him? Exactly when was the stock transferred to Brown’s son, and on what terms? Does he intend to reclaim it upon leaving office?

In recent weeks, Brown has come under fire from Rep. William F. Clinger Jr. (R-Pa.), chairman of the House Government Reform and Oversight Committee that is investigating Brown’s finances, for seeming to mask $400,000 in revenue he received from another company, First International Communications Corp., while he was commerce secretary. Brown had invested no money in First International and the company never made a successful investment. First International’s sole income was interest on a note it held from a related firm that defaulted on a $24-million government-held loan.

With his holdings in First International--as with Kellee--a primary issue being raised is Brown’s preference for secrecy. If he did nothing wrong in his handling of these investments, his critics ask, why did he take steps to keep them from being publicly disclosed?

As a result of these and other unanswered questions, Brown’s financial affairs are under investigation by the Justice Department and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., as well as Clinger’s congressional committee.

Brown told Commerce Department officials who reviewed his financial affairs that he divested himself of stock in Kellee, which is run by James R. Kelly III, husband of former Washington Mayor Sharon Pratt Kelly, on June 15, 1993. The secretary pledged to avoid participating in any Commerce Department issue directly affecting Kellee during his first year in office.

He did not distance himself from matters involving AT&T;, however. Nor did he recuse himself from taking action affecting the telecommunications industry in general, although he retained considerable holdings in that sector, including a Washington radio station and the controversial involvement with First International.

At a minimum, Brown failed to dispose of Kellee stock within the usual 90-day period required by the Office of Government Ethics. Some of Kellee’s business records also raise questions about whether he truly got rid of the stock on June 15, 1993, as he said he did.

Nor was he entirely forthcoming about his handling of the matter.

In May, 1994, when Brown released his financial disclosure report for the 1993 calendar year, Kellee--along with one other investment--had simply disappeared from his list of holdings without explanation. Despite repeated queries from members of Congress, Brown refused to say how he had disposed of them.

Officials at LAX, meanwhile, were not notified until this year that Brown was no longer a stockholder in Kellee Communications. An official airport document dated Jan. 12, 1994--six months after Brown claims to have divested himself of his interest in the company--says he then owned an 8.9% share in Kellee. The document is based on information supplied in writing by principal stockholder James Kelly, who told airport officials that ownership of Kellee had not changed since 1990.

Not until September, 1994--more than a year and a half after Brown became commerce secretary--did Kellee disclose in an application for a similar contract at Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport that Brown had transferred most of his Kellee stock into the name of his adult son, Michael, a Washington lobbyist.

Although Brown refuses to discuss the details of his past and present financial holdings, he steadfastly insists his ethics are above reproach.

“At no time during my tenure as secretary have I been involved in any matter which would cause a conflict of interest or create an appearance of conflict of interest,” he said in a recent letter to Clinger.

In addition, Carol Hamilton, Brown’s press secretary, said his handling of his Kellee interest was entirely proper and within the government ethics rules. “This is a non-story,” she said.

As officials at the Office of Government Ethics see it, Brown had an obligation to tell Commerce Department attorneys who were reviewing his portfolio for conflicts about the company’s close relationship to AT&T.;

Donald E. Campbell, deputy director of the ethics office, which administers the 1978 Ethics in Government Act, said he thinks Brown should have disclosed the link so that Commerce Department ethics lawyers who reviewed his financial situation could have made a more informed judgment about the potential for conflict.

“There has to be enough information disclosed to the ethics officer for them to make an informed judgment,” Campbell said.

Barbara Fredericks, a Brown appointee and the Commerce Department’s chief ethics officer, contends, on the other hand, that it was not necessary for Brown to disclose Kellee’s link to AT&T; or even to divest himself of the Kellee stock.

“Why did he divest?” she said. “I can’t jump into his mind.”

Although the law plainly states that a Cabinet officer cannot hold even one share of stock in a company with business before the department, Fredericks said, it does not prescribe clear guidelines for handling a situation in which the link is indirect.

Since Kellee’s business relationship with AT&T; was confined to specific ventures inside the United States, the Saudi contract would presumably have no direct impact on the revenue of the Kellee-AT&T; partnership. But indirectly, analysts say, all of AT&T;’s business partners could enjoy some benefit from a contract that will boost the company’s revenue by $600 million a year.

Beginning with the LAX contract, AT&T; has expanded its dealings with Kellee to give that company a similar share of pay telephone business at other major airports, including Hartsfield in Atlanta, Ontario International Airport in San Bernardino County and Chicago’s O’Hare. As a result, the value of Kellee’s stock has likely risen.

The origins of the AT&T-Kellee; relationship date back to the Administration of Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, who led the way for minority participation in municipal contracts.

To win the contract to supply pay telephone service at LAX in 1989, AT&T; was required by the Bradley Administration to find minority and female business partners. The result was A/K/O-LAX, a joint partnership organized by AT&T; that included Kellee, a minority-owned firm, and Own-A-Phone, a female-owned business.

The partnership agreement called for Kellee to own and maintain about 20% of the 1,300 pay telephones at LAX, to collect the change from those phones and to share in AT&T;’s revenue from long-distance calls made on the phones.

At the time the contract initially came up for bid, airport documents show, about 80 companies bid on it. Airport Department officials reported receiving inquiries about the bidding process from several prominent politicians in the state, including Bradley, Los Angeles City Councilmen John Ferraro and Zev Yaroslavsky, and ex-Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown Sr.

According to Fritz Mayer, who helped oversee the formation of the partnership for AT&T;, Kellee was chosen for a 20% share because it was the most qualified. Kellee already operated about 200 pay phones in New York and New Jersey, many located in liquor stores in low-income neighborhoods.

While the choice was made on merit, Mayer said, James Kelly punctuated his conversations with references to Brown, who was then on the verge of becoming chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and his other high-profile African American directors, including the late tennis star Arthur Ashe.

Brown, who initially purchased 2,000 shares in Kellee on June 1, 1988--five days before the firm applied for the LAX contract--acquired an additional 113,992 shares a year later, shortly after A/K/O won the contract. City records indicate that the initial stock sold for 50 cents a share, but there is no record of what Brown may have paid.

The LAX contract proved to be profitable for Kellee’s owners as well as for AT&T.;

Kellee’s annual revenue shot up from $200,000 in 1987 to $2.4 million in 1992, and AT&T;’s decision to extend its relationship with Kellee to other major airports has presumably boosted revenue still further.

Overall, according to AT&T; officials, the A/K/O partnership at LAX generated annual revenue of at least $10 million, making it among the most lucrative airport pay phone contracts in the nation. It was so profitable that AT&T; fought hard recently to beat out MCI for a new five-year agreement--this time with Kellee and Own-A-Phone as subcontractors.

At the time Brown took office, AT&T; was plainly seeking the Commerce Department’s help in international sales and in toppling barriers that stood in the way of its exporting telecommunications equipment to countries around the globe. Ever since federal courts broke up its monopoly on U.S. telephone service, AT&T; had been looking for growth overseas.

From the start of his service as commerce secretary, Brown has publicly supported that goal, as he has the efforts of other American companies to expand abroad.

In May, 1994, when Brown released his financial disclosure report for the 1993 calendar year, Kellee--along with one other investment--had simply disappeared from his list of holdings without explanation. Despite repeated queries from members of Congress, Brown refused to say how he had disposed of them.

On June 9, 1993--a week before Brown claims to have divested himself of his Kellee stock--AT&T; approached the Commerce Department seeking assistance on another matter. The company was seeking relief from rules imposed by the Western allies’ Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM), which restricted the export of sophisticated telecommunications equipment to the former Soviet states and China for security reasons.

On Dec. 11, 1993, the department ruled in AT&T;’s favor, finding that the equipment was available to China from other sources. (COCOM was later disbanded.)

Brown has helped AT&T; in other parts of the world as well. AT&T; executives accompanied Brown on trade missions to South Africa and Russia. He also met with overseas AT&T; officials while on a recent trade mission to India.

According to press secretary Hamilton, Brown has done nothing for AT&T; that he would not do for any other American company, nor has he expressed interest in reclaiming his Kellee stock from his son when he leaves office.

Inside Washington

* A collection of stories from The Times Washington Bureau takes you inside the Beltway for a firsthand look at the figures and foibles of the federal government. Sign on to the TimesLink on-line service and “jump” to keyword “Washington.”

Details on Times electronic services, A8

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.