Treatment Cures Brain Tumors in Rats : Medicine: The therapy will be tested on human cancer patients this year. A specially modified retrovirus inserts its genes into DNA and destroys only malignant cells.

Government scientists have developed an unusual new form of gene therapy to treat inoperable brain tumors and plan to begin human trials this summer.

The new approach, which has cured brain tumors in rats, takes advantage of the fact that brain cells do not normally divide and multiply, while tumor cells multiply rapidly.

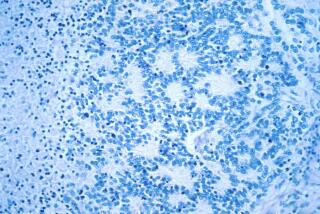

Researchers at the National Cancer Institute injected the tumors with mouse cells containing a specially modified virus that infects only dividing cells. The virus also carries the gene for a protein that makes the tumor cells susceptible to treatment with the antiviral drug ganciclovir.

Oncologist Kenneth Culver and his colleagues report today in the journal Science that 80% of rats treated by this approach were cured of their cancers and that the remaining 20% had only a few residual tumor cells.

âItâs like putting bullâs eyes in the tumors and shooting them,â said Nelson Wivel, director of the National Institutes of Health office of recombinant DNA activities.

âItâs a very innovative approach to brain tumors . . . that could have significant impact if we are able to follow up on it,â said NCI head Samuel Broder. âWe need to emphasize that this is not yet a cure for brain tumors in human beings, but it really is very novel.â

About 35,000 Americans develop brain tumors each year and the majority of them die of the cancer. âWe donât save many of these patients with current treatment, so we need a new treatment that will help them,â said cancer institute neurosurgeon Zvi Ram, one of the researchers who will head the clinical trials.

The technique may have much broader impact, Culver said in a telephone interview. The team has already cured liver cancers in rats with the technique and is now looking at pancreas and stomach tumors.

âThe whole idea is to develop a therapy that could be easily administered and used around the world, even in the poorest countries,â Culver said. âIt was quite thrilling when we saw the dramatic results.â

Thirteen clinical trials of gene therapy are under way and several more are scheduled to begin this year. In all other gene therapy trials that involve viruses, target cells are removed from the body, treated with a virus that is unable to infect other cells and then injected back into the body.

In this case, however, surgeons are unable to remove tumor cells without damaging the brain, so they must rely on the ability of the virus to infect the tumor cells within the brain, maximizing the destructive effect of the therapy.

Opponents of gene therapy have argued that modified viruses could infect cells other than those they are targeting, producing severe side effects. But it is unlikely that any of the injected mouse cells will be able to pass through the blood-brain barrier to infect cells elsewhere in the body, Culver said. And if a few of the mouse cells should escape the brain, he added, the patientâs immune system should destroy them quickly.

Culver said the team has seen no evidence of such unwanted infections in any of the animals studied.

The virus Culver employs is called a retrovirus because it has the ability to insert its genes into the DNA--deoxyribonucleic acid, the genetic blueprint of life--of the infected cell. In addition to its ability to kill dividing cells, the virus has been armed with a gene that activates the antiviral drug ganciclovir. Normally, ganciclovir has a very limited ability to kill cells. But the protein produced by the gene converts it into a different form that is much more toxic. Because the conversion is carried out inside the tumor cells, the toxic form does not attack healthy cells.

Culver and his colleagues also observed an unexpected effect of the therapy that they call the âbystander effect.â Not all of the tumor cells are infected by the retrovirus. But for reasons that are still unknown, uninfected tumor cells also become more susceptible to the killing effects of ganciclovir after the treatment.

Ram and NCI neurosurgeon Edward H. Oldfield received permission from the National Institutes of Health last week to begin the clinical trials in the next few months. They must also obtain approval from the Food and Drug Administration, but such approval seems likely, they said.

They plan to begin with three patients who have life expectancies of less than 3 months. If the retrovirus and the cells do not cause any significant side effects in these three patients, the trial will be expanded to 20 patients.