Mexicans aren’t counting on the government to rescue them. They’re saving themselves

Reporting from Mexico City — In the moments after the earthquake, they didn’t cower, they mobilized.

By the tens of thousands, volunteers streamed toward the Mexico City neighborhoods most damaged by Tuesday’s violent temblor. Some carried shovels, others hauled donations of food and water. Many simply offered up two good hands.

They weren’t public authorities or professionals. They were ordinary Mexicans who knew from experience that during a crisis such as an earthquake, it’s better to do things yourself than to rely on the government for help.

Exactly 32 years before this week’s magnitude 7.1 earthquake brought down dozens of buildings and killed more than 270 people across central Mexico, a more devastating temblor leveled a much vaster stretch of Mexico City.

Many Mexicans remember the 1985 earthquake not only for its destruction but also for the government’s lackluster response.

“The government pretty much disappeared for the first 24 hours,” said Alejandro Hope, a political and security analyst who was 14 at the time of the 1985 quake.

With scores trapped beneath the rubble and many more in need of other assistance, “the army was just blocking the streets, not helping particularly,” he said. It was days before then-President Miguel de la Madrid visited a rescue site, he said.

Manuel Montes, a geological engineer, was 33 when the ’85 earthquake hit.

“The government was frightened, there wasn’t an immediate response from the city or federal government,” he said.

In the aftermath, citizens were left to deal with a frightening new reality.

“I went to look for a friend, and there were piles of bodies,” he said. “You don’t see that today. At that time, the city smelled of death. There were areas you couldn’t go to because it reeked of death.”

According to Hope, the real heroes then were the civilians who stepped up, often moving debris with bare hands.

If ordinary Mexicans learned a lesson from the disaster, so too did Mexico’s politicians. Anger about the government’s response — it refused to accept international aid for several days, and it suppressed estimates of the number of dead — helped turn opinion against De la Madrid’s Institutional Revolutionary Party.

The response of current President Enrique Peña Nieto, who deployed more than 3,000 soldiers to help and visited a rescue site the first day of the earthquake, shows that politicians learned “that the only thing you cannot do during a disaster is hide,” Hope said.

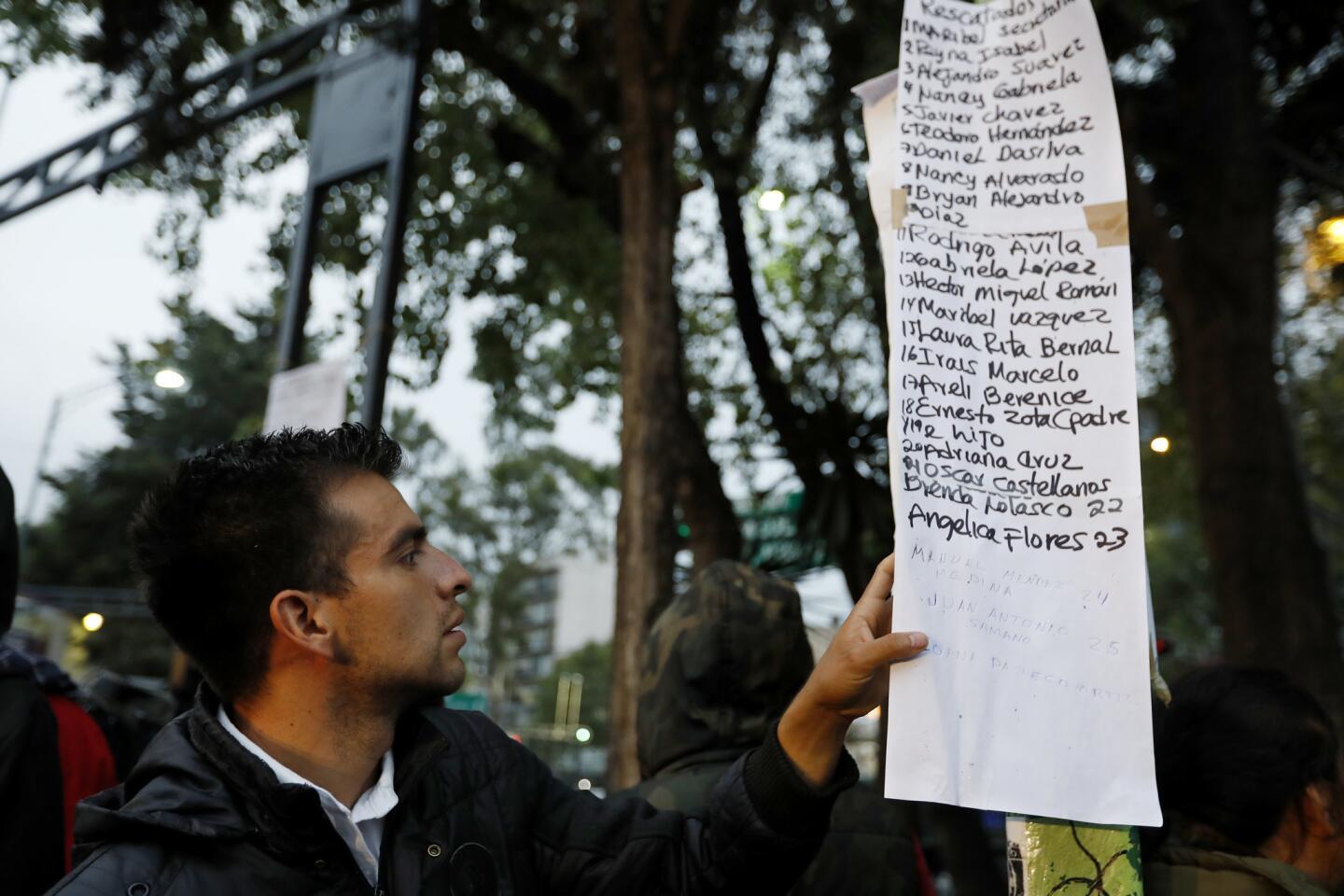

Despite quick government action, volunteers showed up, in many areas forming human chains to deliver aid supplies or move rubble, or warn pedestrians against getting near dangerous sites.

They worked all day, all night, all day and all night again.

Paramanand Kaur, an event organizer who lives in Mexico City’s Condesa neighborhood, said she had slept only one hour since the earthquake. After it struck, she ran to a collapsed building and began handing out masks to the volunteers who were helping move debris.

On a nearby street corner, she accepted a donation of a few flats of water bottles. It quickly evolved into one of the city’s most active donation sites, with people streaming in constantly with donations of tools, food and medical supplies, and she has operated it ever since.

“My neighborhood was in chaos. I can’t stay in my house,” she said.

At first, government officials told her no more help was needed. But volunteers continued showing up with donations and to offer help at rescue sites. “They finally decided it was better that we work together,” she said. “Because people aren’t going to stop helping.”

Outside a collapsed office building a few blocks away, about a hundred volunteers lined up Thursday morning to take over for crews that had worked all night.

“We’re normally so divided,” said Jose Funcia, 32, who was waiting in line with a shovel. Those divisions are across economic and cultural lines, he said. “But when it’s an emergency, we come together.”

The signs of generosity appeared in more subtle ways too: Restaurants advertised free lunches, while neighbors set up power strips in their windows to allow responders to charge their phones. On Facebook, messages spread inviting the newly homeless to sleep in guest rooms and on couches. Even those directly affected purchased supplies to donate to others in need.

At times, tensions rose between these good Samaritans and officials charged with the rescue effort.

At a building in the Roma neighborhood that had previously housed a mattress store and offices, volunteers received word that a survivor might be in the rubble — or perhaps not. Desperate to help, volunteers lined up along surrounding blocks with shovels and pickaxes, while others outfitted them with gloves and face masks.

Behind caution tape, a backhoe combed through the remains of the building, prompting an outcry from volunteers who feared the heavy equipment would harm those who might still be trapped. They began shouting at soldiers, armed with automatic weapons, who were blocking access to the site.

The victims’ blood would be on their hands, people shouted. The guards stood their ground, making no eye contact with the volunteers.

The moment highlighted an inherent distrust between the public and officialdom in Mexico, where corruption is endemic and official violence is one of the tools used in its service.

Anais Martinez, a gastronomic tour guide, counts herself as usually distrustful of government officials. But when her apartment building suffered extreme damage during the earthquake this week, civil defense authorities came by quickly to evaluate and leave instructions — don’t move furniture, enter for only five-minute intervals to collect belongings, leave the rest behind.

She found herself feeling differently.

“In cases of emergency,” she said, “I think they take away the title of government officials and become fellow Mexican brothers.”

Twitter: @katelinthicum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.