BAJA CALIFORNIA, Mexico â Six months after Barbara Martinezâs son disappeared, the nightmares began.

âI would close my eyes, but then I would see him buried under the ground, but with his eyes open, and stuck there, looking up at me like this,â Martinez said Thursday, making a face to show how she imagined her dead son shot desperate looks at her from beneath the blackness of his undiscovered grave.

She couldnât sleep or eat. She could only think about finding her son.

CĂŠsar Ezequiel Rico de la Cerda, her 17-year-old child, disappeared from Tijuanaâs southeast Urbi Villa Del Prado II neighborhood in October 2018.

Martinez is among thousands of parents and family members who have formed collectives throughout Mexico to help one another search for the remains of their missing children. Itâs a response to what they describe as failure by the Mexican government to protect or search for their missing children.

Though Martinez believes her sonâs remains are located in a home in Tijuana, she travels to places such as Poza Rica, Veracruz, near Mexicoâs eastern coast, as an act of solidarity with members of her group, the Collective of Mothers Searching for Their Lost Treasures.

Parent groups spend weeks at a time searching rugged and remote areas nationwide for clandestine mass graves, known as fosas clandestinas.

Last week, the groups descended on remote hills in eastern Tijuana after discovering dozens of bodies buried there. As is often the case, it started with an anonymous tip to one of the parent organizations and directions to an isolated burial ground â a place where criminals know they can discard bodies, according to the president of one of the collectives.

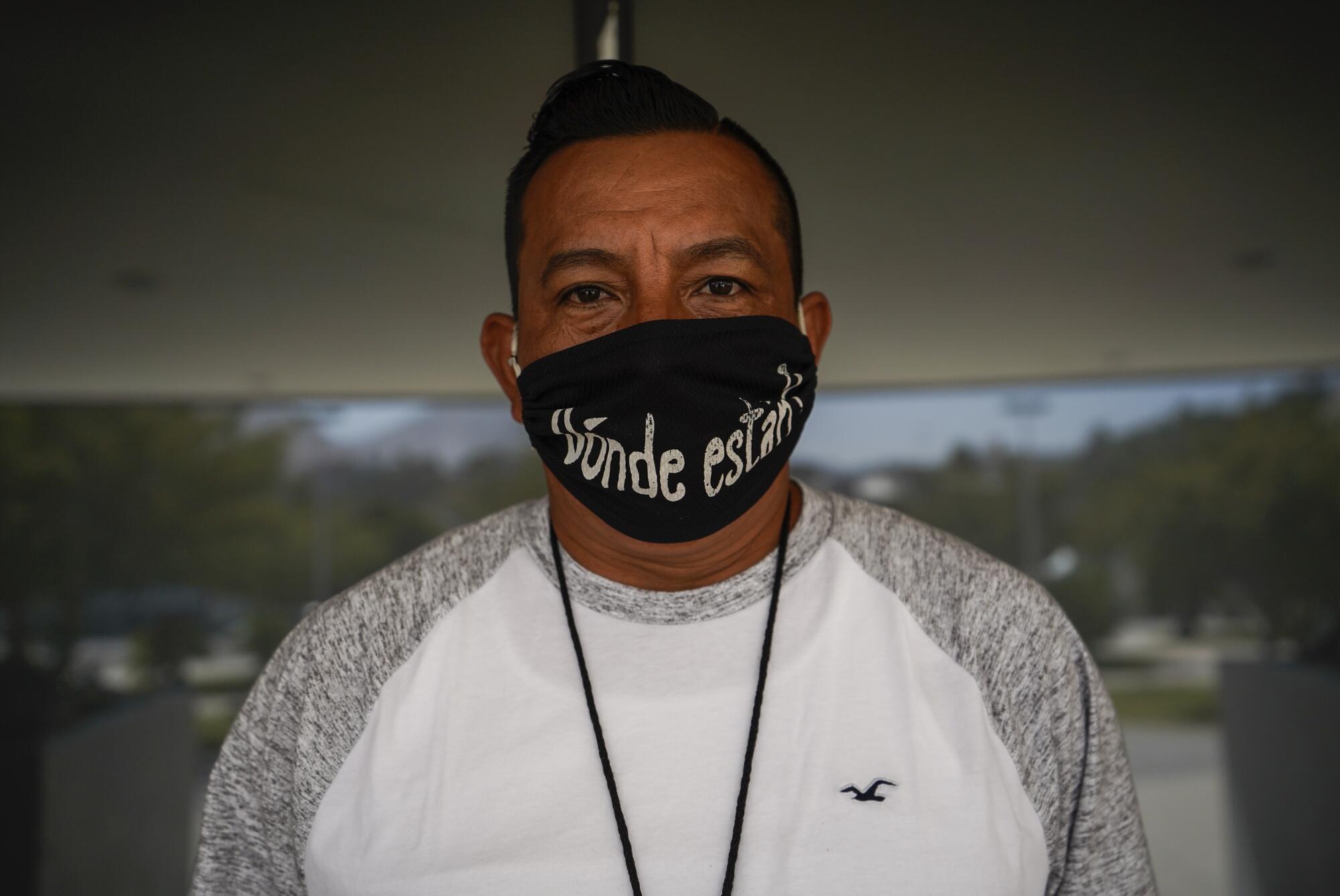

âIt was a phone call to my colleague ... who was given an exact point where he would find a body,â said Jesus Varajas Chairez, a Riverside resident and president of Buscando a Tolando, or Searching for Tolando, his missing brother.

A few of the men went first on the search, well aware the area was probably guarded by armed cartel members.

âWe just kept looking and we kept finding more and more ... until we realized what it was,â Varajas said. Word spread quickly and others joined the search.

The collectivesâ existence is a testimony to Mexicoâs national tragedy.

In January, the Mexican government released a report estimating 61,637 citizens disappeared between 2006 and December 2019. The vast majority are young men in their early 20s. Itâs the hidden toll of the countryâs U.S.-backed war against drug gangs, which has only grown more violent and more powerful.

âBaja California is basically ground zero for modern drug war disappearances in Mexico,â said Michael Lettieri, a PhD and senior fellow for human rights at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at UC San Diego.

âItâs just the history and the nature of the drug war in Mexico and the official complicity, and the official failure to find missing people,â Lettieri said. âIt has a pretty long history in Baja, longer than in other places that are now the hot spots.â

In 2019, Tijuana again easily topped the list of Mexican cities with the most homicides, its 2,185 documented killings once again earning the border city of approximately 1.8 million people the infamous title of the âmost violent city in the world,â according to the Citizensâ Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice.

Investigators said the root cause of the most recent bloodshed in Tijuana is a shift over the last several years that has seen lower-level drug dealers battling over street corners to control the local methamphetamine market in Tijuana.

âEs entre ellosâ is a common refrain of local police â âitâs between them.â The phrase implies the bloodshed is between deserving criminal elements and unworthy of investigation.

âReally, thereâs a serial killer, and itâs government indifference and complicity,â Lettieri said.

Law enforcement officials also say the rise of the Jalisco New Generation cartel, also known by the Spanish acronym CJNG, which has gained power by forging alliances with remnants of the once-powerful Arellano Felix cartel, has contributed to the rising violence specifically in Tijuana.

The collectives have shifted their searches to other places in Mexico, Lettieri said, but the concept was born in the state of Baja California, where parents first began forming alliances to pressure the Mexican government to aid in their search for missing children.

When they met too much resistance, the parent groups began conducting the searches themselves.

The parents purchase their own shovels and pointed metal sticks, which they use to poke into the ground to search for bodies. They take anonymous tips and run down leads â work they say local detectives are too afraid to do. Sometimes, they say, they locate hidden grave sites by smell.

In a country wrought by never-ending violence, the parents also act as support group and grief counselor for one another. And they keep track of one another when their searches take them to some of Mexicoâs most dangerous street corners.

Though most have no experience in politics, the parent groups form complex political alliances aimed at lobbying state officials for relief.

A dozen such parent collectives in Baja California formed into a bigger union called the United Assn. of Baja Californiaâs Missing. It met Thursday with state officials hoping to pressure them to do more to find their missing loved ones and expedite the forensic processing of their recent discoveries.

A state official from the attorney generalâs office stressed Thursday that it has a shortage of funds for missing-persons investigations, with most of the stateâs investigative resources going toward homicide investigations.

Some $500,000 that was supposed to be budgeted for the missing-persons department in 2020 was never delivered because of an error by the past administration, according to the current director, Juan Manuel LeĂłn MartĂnez. Though the new state government has tried to correct the mistake, he said, budgets remain tight.

The result is that only six agents are left to investigate more than 5,000 missing-persons cases in Baja California, state officials said.

Barbara Martinez rejects that explanation. âTheyâre afraid,â she said of the local police. âIf they start investigating, theyâll get threatened by the cartels, so theyâre basically too afraid to do their job.â

Martinez, 40, takes time off work as a home caregiver and from raising her two other boys, 8 and 16, to join the searches. She says the state should help reimburse victims of violent crime for the time they invest in their own family memberâs investigations, the materials and their costs to drive to remote areas.

âSome of our members donât have cars and theyâre scraping together money for taxis,â she said.

Parents say police often assume their children were involved in something criminal and imply they deserved their fate, as a way to shirk responsibility to investigate.

âItâs a re-victimization,â Martinez said. âMany people donât even go to police to report their missing loved ones because they know how they will be treated. I told them it didnât matter if my son was the worst person they could imagine, they still needed to go do their job.â

The latest discovery renewed that hope and anger for family members.

Eighty of them traveled to Tijuana last week to provide federal investigators with DNA samples to determine whether their missing family members were among the newly found bodies.

Among them is Eddy Carrillo, whose 20-year-old son, Erick, lived in Los Angeles and disappeared after leaving a bar in Tijuanaâs El Dorado neighborhood in June 2019. He was vacationing in Mexico with his brothers at the time, visiting their mother.

Carrillo, now the president of the Tijuana collective All of Us Are Erick Carrillo, relocated from San Diego to Tijuana this year to continue the search.

âI am never going to stop looking for my son,â Carrillo said. He has become frustrated trying to enlist the help of the FBI and Baja Californiaâs attorney general. âItâs very difficult as a father to know your son is missing. Iâm here to support all these parents with missing children. Weâre going to find our kids.â

The search can be harrowing.

Not long after her nightmares began, Martinez started receiving anonymous messages on Facebook and WhatsApp from someone who said he was a friend of her son.

âYouâre wasting your time searching in the hills for your sonâs body. Cesar is buried under the bathroom of a house.â

Days later, she said, the person who sent her the messages was found shot dead in the street, a casualty of Tijuanaâs raging drug violence.

Martinez says the killing eliminated the only witness she was aware of. Later, more messages would come, but with a different tone, and a warning.

âYou want to know exactly how I killed your son? You want to know how I tortured him?â

âLook at me. Iâm already dead inside. Iâm like the walking dead,â she said. âThey took my son from me, and thereâs not much more they could do to me.â

In November 2019, Martinez found the body of her sonâs best friend buried near the house in Tijuana where she believes her sonâs corpse is located.

Anonymous messages led her to a home in the Campos neighborhood. Martinez said a tipster sent her photos directing her to the partially constructed house on Calle Rosales.

âI knocked on the door and the people who answered told me they were renting the place. They said I could come back the next day and ask the owners if I could search the property,â she recounted. âThe next day, when I returned, the house was completely empty. The doors were open to the street. Everything was cleaned out.â

She brought shovels and friends and started digging.

State prosecutors threatened her with arrest for entering the property without permission, she said. She is waiting for a meeting next week with a prosecutor who has promised to obtain a search warrant.

âIf it costs me my life, Iâm taking my sonâs body out of that house,â she said Thursday.

A spokesman for the state prosecutorâs office declined to comment about the specifics of her sonâs case.

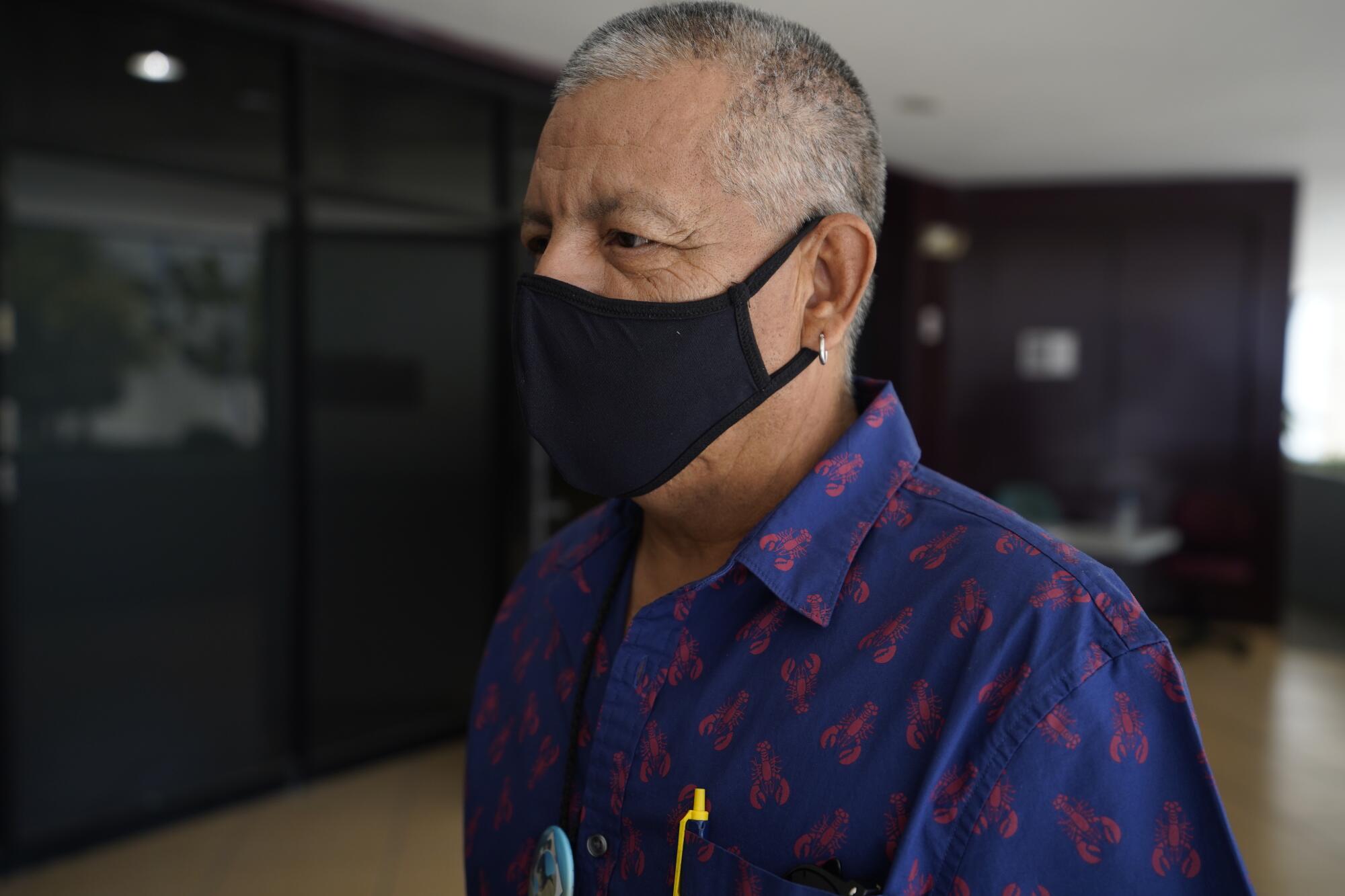

Carlos Flores, the commissioner of state security and investigation guard for Baja California, stressed that in order for authorities to get a handle on the violence in Tijuana, police must eliminate the impunity with which criminals operate across Mexico.

According to data from Mexicoâs National Institute of Statistics and Geography, the country had 154,557 homicides between 2010 and 2016, and in 95% of those cases no one has been convicted. In Baja California, 6,443 people were slain during the same period and just 252 people were sentenced for those crimes â less than 4%.

Martinez said the impunity goes all the way to the top.

She fumed about how Mexican President AndrĂŠs Manuel LĂłpez Obrador in March greeted the mother of JoaquĂn âEl Chapoâ GuzmĂĄn, the famous drug cartel boss who was sentenced to life in prison in the United States last year.

âHe got down from his car to go greet her,â she said, shaking her head angrily. âHow about he greets all the mothers of the children who have gone missing because of El Chapo?â

Fry writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.