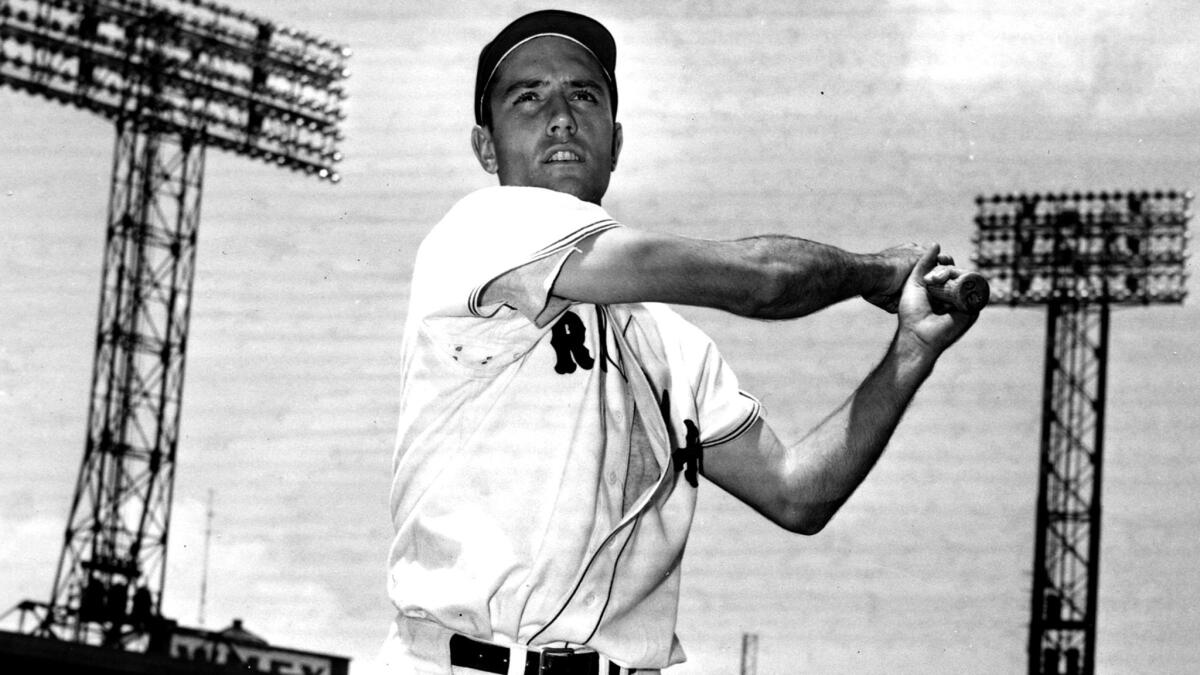

Jim Piersall, one of the first pro athletes to openly discuss mental illness, dies at 87

Reporting from BOSTON â Former major leaguer Jim Piersall, who bared his soul about his struggles with mental illness in his book âFear Strikes Out,â has died. He was 87.

Piersall died Saturday at a care facility in Wheaton, Ill., after a months-long illness, according to the Boston Red Sox, for whom Piersall played for seven of his 17 seasons in the majors.

Piersallâs on-field antics when he first broke into the majors with the Red Sox full-time in 1952 cracked up fans and provided fodder for newspaper columnists. In one game against the St. Louis Browns, he made pig noises and mocked the odd throwing motion of aging Hall of Fame pitcher Satchel Paige.

But Piersall also had furious arguments with umpires, broke down sobbing one day when told he wouldnât play and got into a fistfight with the New York Yankeesâ Billy Martin at Fenway Park, followed minutes later by a scuffle with a teammate.

âAlmost everybody except the umpires and the Red Sox thought I was a riot,â Piersall said in the 1955 autobiography, later made into a movie starring Anthony Perkins and Karl Malden. âMy wife knew I was sick, yet she was helpless to stop my mad rush towards a mental collapse. The Red Sox couldnât figure out how to handle me. I was a problem child.â

He played 56 games in the majors before being admitted to a mental hospital with what was later diagnosed as bipolar disorder. He wrote in his book that he had almost no memory of the season or his time in the hospital.

He returned to the majors in 1953 âsound and healthyâ thanks to âshock treatments, faith, a wonderful wife, a fine doctor and loyal friends.â

He went public to shatter societyâs stereotypes of the mentally ill.

âI want the world to know that people like me who have returned from the half-world of mental oblivion are not forever contaminated,â he wrote.

Piersall distanced himself from the 1957 movie, claiming it was largely fictional and portrayed his father too negatively.

Although he never descended to the depths of mental illness of that first season, he embraced the notoriety it brought him and remained a loose cannon known for his crowd-pleasing stunts and mercurial temper.

âProbably the best thing that ever happened to me was going nuts,â he wrote in his second book, âThe Truth Hurts.â

He was ejected from a game in July 1960 while playing for the Cleveland Indians for running around and waving his arms in center field to distract Ted Williams at the plate.

In September 1962, while with the Washington Senators, Piersall was arrested after going into the stands to confront a heckling fan.

In June 1963, while with the New York Mets, Piersall backpedaled around the bases after hitting his 100th career home run.

Following his playing career, he tried his hand at acting, appearing in an episode of âThe Lucy Showâ with Lucille Ball. He was the general manager of a minor league football team; a hotel manager; a minor league baseball manager; major league front office promotions assistant; and broadcaster.

He was fired from the Chicago White Sox radio crew in 1983 for being too critical of the players and manager Tony LaRussa on air.

An outfielder known more for his fielding skills than his bat, he played in the majors until 1967 for the Red Sox, Indians, Senators, Mets and Angels. He compiled a lifetime .272 average, played in two All-Star Games and won two Gold Gloves.

Piersall was the godfather of former U.S. Rep. Mark Foley, the Florida Republican who resigned in September 2006 after sending sexually suggestive instant messages to former male pages. Piersall became friends with Foleyâs father, Newton police officer Ed Foley, when the families lived next door to each other.

James Anthony Piersall was born during the Depression in Waterbury, Conn. He was raised a Red Sox fan by his father, a house painter, who went long stretches without work, forcing the family to survive on handouts.

Piersallâs father, sometimes distant emotionally, pushed his son relentlessly in baseball from a young age.

Piersallâs mother was committed to a mental hospital when Piersall was a child. As a teen and young adult, Piersall was plagued by severe anxiety, unbearable headaches and sleeplessness as he worried about his future. Piersall is survived by his wife, Jan; nine children; and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.