Analysis: In debate after Paris attacks, Clinton earns the advantage on foreign policy

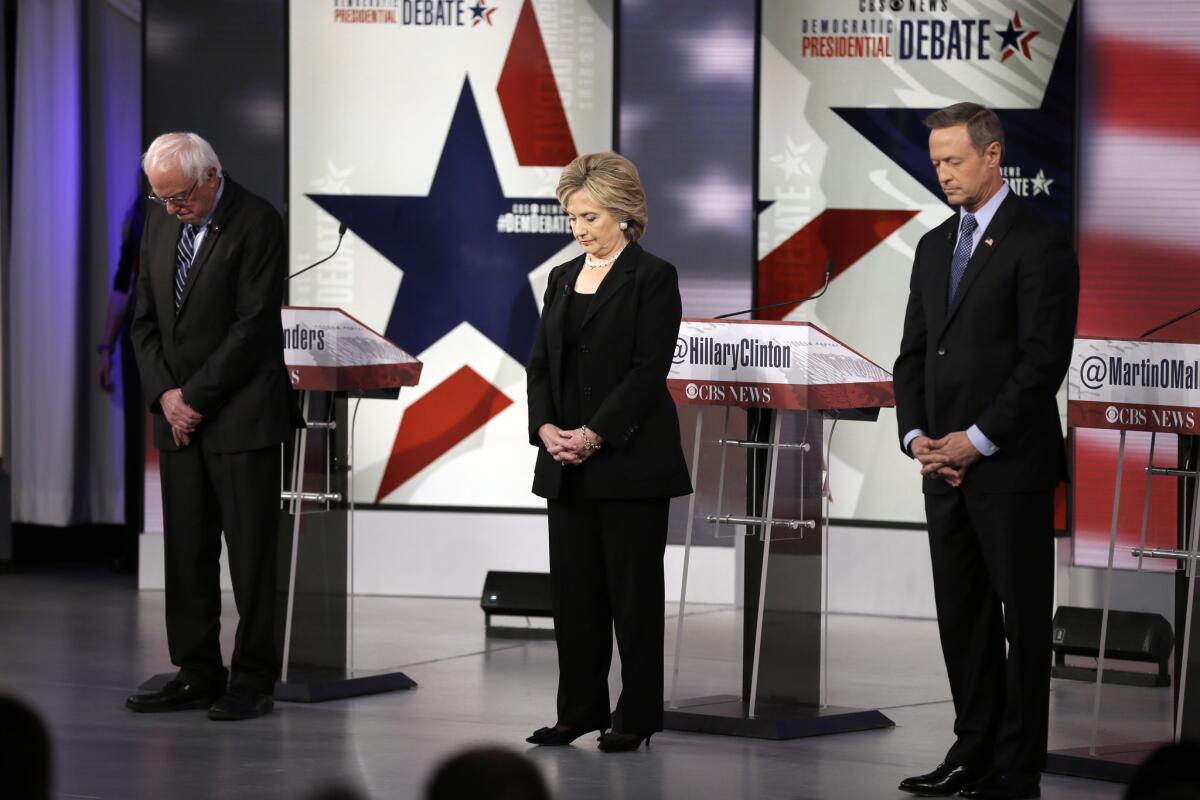

Democratic presidential candidates Bernie Sanders, Hillary Rodham Clinton and Martin OâMalley stand during a moment of silence for those killed in the Paris terror attack. The three candidates debated Saturday night in Des Moines.

An unsettling yet telling split-screen changed the view of the presidential campaign Saturday night: three Democratic candidates who had come to Iowa to talk about domestic issues found their debate hijacked by a foreign policy crisis dominating the news from a world away.

As metaphors for the last two presidencies go, the turnabout was apt: Both George W. Bush and Barack Obama came into office with domestic issues prime on their minds, only to have conflicts abroad hobble and frustrate their tenures.

Foreign policy, and specifically her vote for the Iraq War, also frustrated Hillary Rodham Clinton in her unsuccessful run for president in 2008. Not even an ad that year asserting that she was most experienced to take the 3 a.m. crisis callâthe implication being that Obama wasnâtâwas enough to overcome Democratsâ embrace of his early opposition to the war.

As much as anything, Saturday nightâs debate in the shocked aftermath of the Paris terrorist attack offered Clinton an opportunity to argue anew that her experience is necessaryâand her opponentsâ is insufficient--for any 3 a.m. call. That allowed her to eclipse her rivals on stage, although in doing so, she may have created vulnerabilities a Republican could exploit next fall.

As a former senator and secretary of State, Clinton spoke with fluency about the contradictory puzzle and complicated players in the Middle East, and the tensions there that already have spilled into violence on the European continent. She recounted her experience helping downtown New York recover from the Sept. 11, 2001, attack (weirdly, however, it was in response to a criticism of her closeness with Wall Street donors).

When asked to recount a crisis that had tested her, she dramatically retold the story of advising President Obama to go after Osama bin Laden in 2011 despite concerns by many in the administration that the mission could fail. And, she noted, she offered the advice without consulting anyone, even her husband, former President Bill Clinton.

It was that question, more than any other, that demonstrated Clintonâs advantage once the focus turned to foreign policy. By contrast, former Maryland Gov. Martin OâMalley recounted the daily tribulations of a mayor and state executive, and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders told of a veteransâ bill, one in which he was not successful in achieving his initial goal and had to negotiate a compromise.

Indeed, discomfort on the part of Sanders and OâMalley was palpable from the start. After a moment of silence for the victims in Paris, the candidates moved to opening statements. Speaking before Clinton, Sanders jumped quickly into his familiar arguments about a ârigged economy,â a âcorrupt campaign finance systemâ and the need for millions of Americans to stand and say that âenough is enough.â

Speaking after Clinton, OâMalley averred that the Paris attacks showed the need for ânew thinking, fresh approaches and new leadership.â But he did not offer any of the first two, and on the third, his mention that he worried about terrorism as a governor only underscored his lack of front-line international experience.

Clinton went right to the point.

âWe need to have a resolve that will bring the world together to root out the kind of radical jihadist ideology that motivates organizations like ISIS, the barbaric, ruthless, violent jihadist, terrorist group,â she said, adding pointedly: âThis election is not only about electing a president. Itâs also about choosing our next commander in chief.â

Clinton did not offer many operational details, apart from working with American allies on a united anti-jihadist front. But neither did her opponents.

The Democratic frontrunner undoubtedly would have received a rougher going-over had the debate been against a Republican free to oppose her actions as secretary of State from a perspective 180 degrees opposite hers (and all of the GOP candidatesâ views are.) Her weakest moment came in a muddled response to an obvious question about President Obamaâs failureâand hers--to anticipate the powerful rise of the Islamic State militants. Thatâs a point Republicans are sure to hammer.

Clinton seemed intent on carefully navigating her partyâs shoals. She mildly distanced herself from Obamaâs ill-timed assertionâdelivered just before the Paris attackâthat the Islamic State was contained. âIt cannot be contained, it must be defeated,â she said.

But she immediately moved to calm the left: âWhat the president has consistently said--which I agree with--is that we will support those who take the fight to ISIS,â she said, citing the U.S. forces training Arab and Kurdish militaries. âBut this cannot be an American fight, although American leadership is essential.â She mentioned the limits of American involvement twice.

The Democratic counter to Clinton was far more difficult to make, giving the debate performances of Sanders and OâMalley the feel of a collection of pulled punches.

Sanders has ridden a wave of support from the partyâs liberal left. Flaying Clinton for being insufficiently aggressive against the Islamic State and other terrorist groups would have inevitably risked a collision with the anti-interventionist views of his supporters, which by all evidence the senator ardently shares. OâMalley, with no clear path to the nomination besides his generational pitch, was effectively in the same fix.

Neither candidate, for example, explicitly hit Clinton on one of the most significant events of her tenure as secretary of State, the loss of four Americans at the U.S. mission in Benghazi, Libya. Republicans have argued that attack would have been prevented by a more aggressive posture.

The irony of terrorism and foreign policy overtaking a Democratic debate is that the partyâs candidates have largely avoided the subject this election cycle.

Republicans have brawled over the level of aggression each would apply in the Mideast, with several candidates advocating no-fly zones that would put the countryâs military in direct conflict with Russian planes operating over Syria. Several also have advocated a sharp rise in American troops overseas.

But for Democrats, the subject has been far more fraught. Obama came to office in the aftermath of Bushâs intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan and vowed to disentangle America from both fights. He has since disappointed some of his followers by announcing that he would keep at least 5,500 troops in Afghanistan beyond the previously announced 2016 withdrawal. He also said recently that he would send special operations troops to Syria to assist rebels there --language that uncomfortably echoes the beginning of involvements in past military theaters.

So for the Democratic candidates there had been no real primary season rationale for a focus on foreign policy. The first Democratic debate stuck to the candidatesâ nuanced differences on issues like economic policy, healthcare and criminal justice, and their agreements on matters such as changing immigration policy and raising the minimum wage.

Then Paris exploded in violence.

Whether terrorism will remain at the forefront of the campaign is impossible to predict, given that nearly a year remains before the election. But if it happens, more detail will be required from both the Democrats and Republicans seeking the White House.

Ironically, as the candidates spoke to a country shaken by the Paris attack and wondering if it could happen here, one question was left unasked Saturday night: If France couldnât find a handful of terrorists in a country of 66 million people, how would the next president find them in a country of 320 million?

For political news and analysis, follow me on Twitter: @cathleendecker . For more on politics, go to latimes.com/decker.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.