On Politics: Why the rise of the independent voter is a political myth

For a party halfway in the grave, the news thudded like another shovelful of dirt — thwack! — heaved atop its coffin: The Republican Party may soon slip into third place among registered California voters, trailing Democrats and self-declared independents.

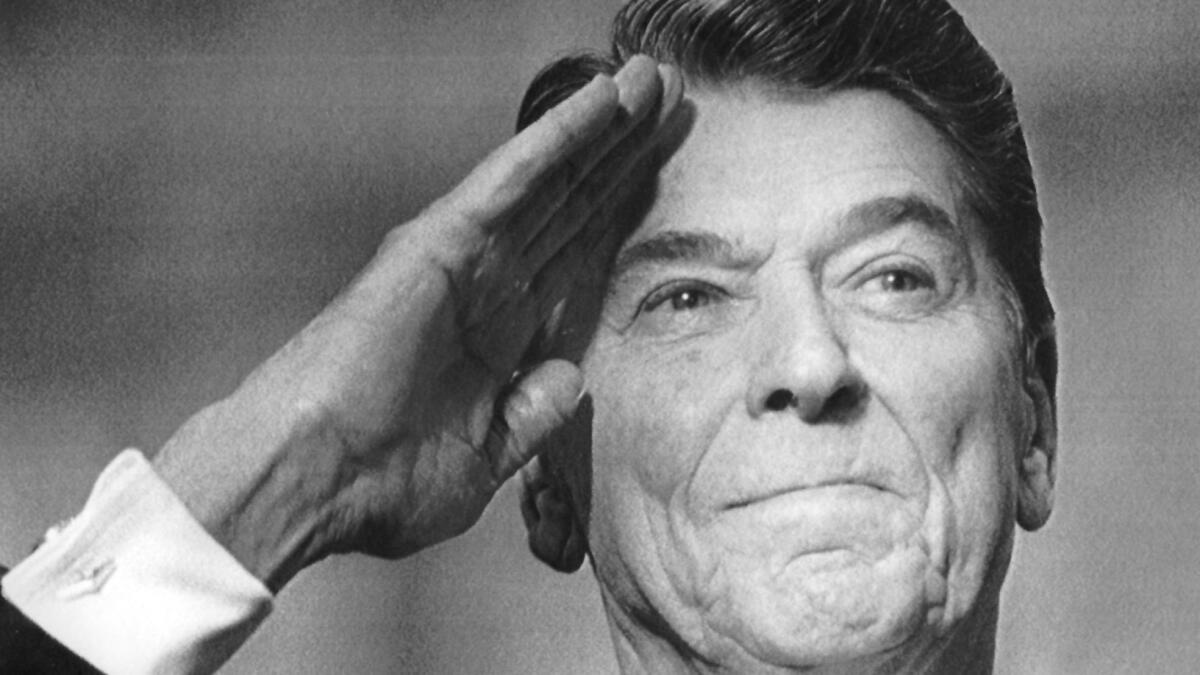

The decline of the GOP — now barely a quarter of the state’s electorate — has been a precipitous one in this formerly deep-red redoubt, a decline all the more striking given the provenance of figures like Earl Warren, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Between them, they represented California on the national ticket in 8 out of 10 presidential races over a nearly 40-year span.

That said, the latest registration figures weren’t that hot for Democrats, either. True, at 45%, the party enjoys a sizable advantage over Republicans. But that level of support has hardly budged in 20 years, even as the party tightened its vise grip on the state.

The significant growth in registration has come in the ranks of California voters who stated no party preference and now make up 25% of the electorate, nearly on a par with Republicans and almost certain to overtake the GOP before long. A little more than 20 years ago, self-described independents were just 12% of the state electorate.

The dramatic rise of the independent voter is one of the popular narratives of our tumultuous political times, not just in California but nationally. It’s also highly misleading.

Mass defections from the two major parties would seem understandable, coinciding with a growing disaffection with any number of once-respected institutions — Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the Roman Catholic Church, the FBI and on. For many, the political parties are emblems of a detested establishment that routinely leaves them choosing at election time among a set of lesser evils.

But the ascendance of the independent voter isn’t what it seems. Indeed, the notion that legions of voters are shunning Democrat and Republican alike to boldly march down a path of utter neutrality is pretty much a myth.

We all like to believe we are our own free agents. What we like to say is we call it as we see it.

— Peter Hart, Democratic pollster, on the prevalence of self-identified “independent” voters.

In 2016, 34% of Americans described themselves as politically independent, more than the 33% who aligned with the Democratic Party and 29% who identified with the GOP, according to a national Pew poll. And yet Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Hillary Clinton — two of the most widely disliked candidates ever nominated by a major party — collectively received 94% of the popular vote.

California voters, faced with a similarly unpalatable choice, behaved no differently.

In 2002, the widely loathed Democratic Gov. Gray Davis faced a hapless and unpopular GOP challenger, Bill Simon Jr. Still, the two combined to receive just under 90% of the gubernatorial vote. (Davis, of course, was booted from office less than a year later, in what amounted to a do-over under California’s recall process.)

The political system is heavily biased to favor the two major parties, and Democrats and Republicans alike do all they can to preserve their combined hold on power.

But scratch not too far below the surface and you will find most independent voters are, in fact, partisans who routinely vote with one party or the other. They simply prefer not to be affixed with any political label; don’t we all cherish our autonomy and freedom to exercise our wise, unparalleled judgment?

“We all like to believe we are our own free agents,” said Peter D. Hart, a Democratic pollster who has spent decades conducting political focus groups and sampling voter opinions. “What we like to say is we call it as we see it.”

Which, for most, lines up time and again with the Democratic or Republican candidate in a campaign.

Experts suggest that independents — true independents, who genuinely favor neither major party and hopscotch among Democratic, Republican or third-party choice depending on the office or election — may constitute as little as 5% of the electorate and are nowhere near the 25% or more that show up in registration numbers and polling.

None of which minimizes the problems facing California’s embattled GOP.

It’s been more than a decade since a Republican won statewide office, and even longer since a Californian seriously vied at the national level. White House hopefuls don’t even bother competing in the state past the primary season, for good reason; all Trump could muster against Clinton in 2016 was a paltry 32% support.

There is a good chance, under the state’s top-two voting system, the party won’t have any candidates running for governor or U.S. Senate in the fall, leaving vulnerable House members stranded with no one atop the ballot to spur Republican turnout.

And even as Democrats salivate at the prospect of a November blowout, the party is facing its own deep divisions between party elders — some of them quite elderly — and a younger, more pugnaciously liberal base demanding a less compromising, more hyper-partisan approach.

The time may seem ripe for a third-party movement, as the blow-up-the-system crowd desires. But the Democratic and Republican duopoly is a long way from dead, regardless of what the polling and voter registration numbers might suggest.

Watch what voters do, not what they say.

@markzbarabak on Twitter

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.