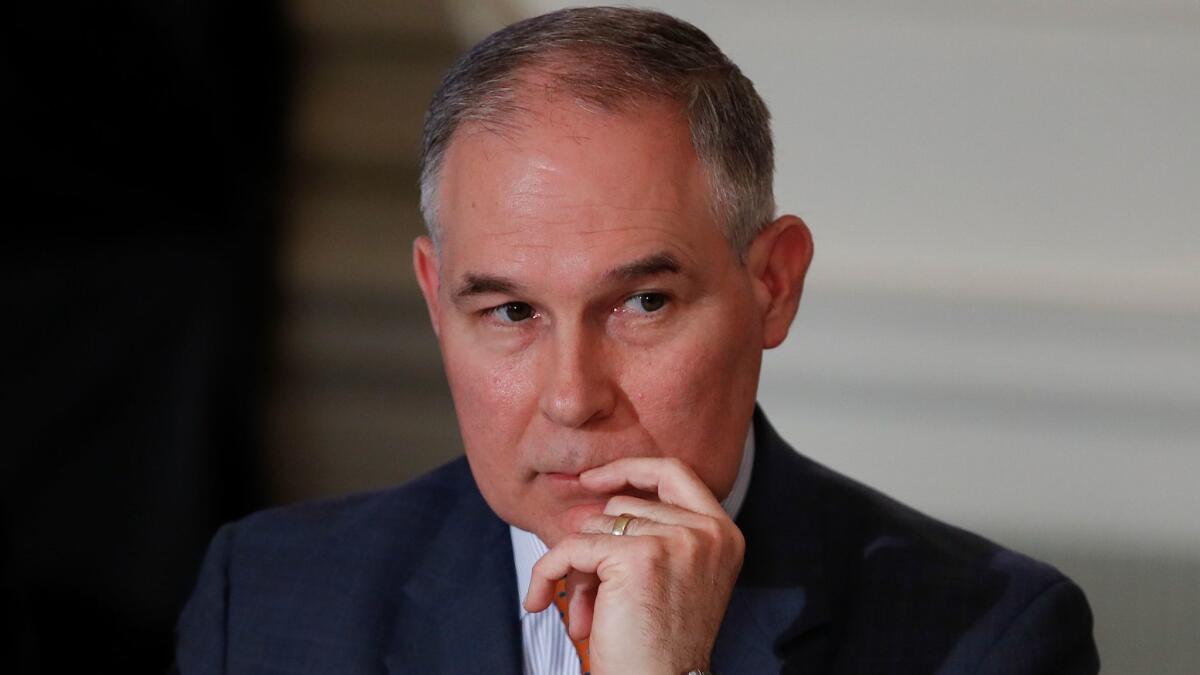

EPA chiefâs clean-water rollback shaped by secrecy, luxury travel and handpicked audiences

Reporting from Washington â As Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt jetted around the country last year, regularly flying first or business class at hefty taxpayer expense, his stated mission was often a noble one: to hear from Americans about how Washington could most effectively and fairly enforce the Clean Water Act.

Yet when Pruitt showed up in North Dakota in August to seek guidance on how to rewrite a landmark Obama-era water protection rule, it was clear there were some voices he did not care to hear.

For the record:

9:30 p.m. March 10, 2018An earlier version of this story said the Trump administration suspended guidelines protecting water in February. The suspension came in late January.

The general public was barred from participating in the roundtable Pruitt presided over at the University of North Dakota. An EPA official even threatened to call security on reporters who tried to linger.

What happened at the meeting is still a mystery to all but the invitees, a list dominated by industry and Pruittâs political allies. The same is true of many of the other 16 such roundtables Pruitt held as he developed his plan to weaken a federal rule that protects the drinking water of 117 million Americans.

Such behind-closed-doors deliberation is a hallmark of the agency under Pruitt, an EPA administrator who spent $25,000 to set up a secure phone booth in his office and said security concerns guided his luxury plane travel. Pruittâs security detail said flying in coach exposed him to too much interaction with hostile members of the public. Under fire for the costly plane tickets, which were revealed in records obtained by the nonprofit watchdog Environmental Integrity Project, Pruitt said this week he would start trying to fly coach when possible.

But the buffer Pruitt has created from critical elements of the public extends beyond his choice of airline seating. It also defines decision making at his agency.

Pruitt purged scientists from an independent EPA advisory board that, among other things, rigorously reviewed the science behind the Obama water rule and found it to be sound. An EPA regulatory reform task force advising Pruitt on the rollback of clean water and air rules operates largely in the shadows. Pruittâs advisors ordered economic data that reflected the benefits of Obamaâs water rule erased from a key federal report, over the objections of career staff at the EPA.

Pruitt rejects any suggestion he is bending the rules. He says the agency is working âthrough the robust public process of providing long-term regulatory certainty across all 50 states about what waters are subject to federal regulation.â

The effort is aimed at removing federal Clean Water Act protection from millions of miles of streams and wetlands, including more than 80% of the waters in California and the arid West. In January, the administration suspended for two years the new guidelines protecting those waters as it scrambles to draft a replacement rule that substantially narrows the reach of the act.

Pruitt is, indeed, making a robust effort to connect with stakeholders â spending a lot of public dollars along the way. But his audiences are typically handpicked, and almost always industry-friendly.

While EPA officials say others have ample opportunity to be heard through pro-forma comment filings, webinars and occasional meetings with staff, many communities feel shut out.

âNo outreach at all was done here,â the Navajo Nation protested in a letter to the EPA weeks before it suspended the clean water rule. The letter contrasted the hasty suspension of the rule with the four years of tribal consultation and scientific review that went into creating it.

There were no such complaints from the National Cattlemenâs Beef Assn., which not only hosted Pruitt on a Colorado ranch, but also persuaded him to star in its advocacy video filmed there. The video urges ranchers to lobby the EPA to weaken the rule. Earlier on the day of the ranch visit, a commercial flight delay moved Pruitt to spend $5,700 of public money on a short-hop charter so he and staff members could stay on schedule.

In the video, Pruitt accused the Obama administration of âreimaginingâ its authority to define waters deserving federal protection to include even puddles â which the previous administration said it had specifically excluded from protection. The attorneys general of nine states, including California, cited the video as evidence that Pruitt, who had sued to scrap the Obama water rule while attorney general of Oklahoma, is not approaching the rewrite with an open mind, as the law requires.

In Pruittâs home state of Oklahoma, the EPA spent $14,400 to charter a plane so Pruitt and his staff could hear from several dozen farmers eager to repeal the rule in the town of Guymon. Soon after, the state of North Dakota spent $2,100 to ferry Pruitt and a couple of staffers to the closed-door meeting there. During the North Dakota visit, EPA staff directed a radio host scheduled to interview Pruitt not to take calls from listeners, according to agency emails published by E&E News. The emails also revealed how EPA staff insisted the roundtable be closed to reporters. âPruitt does not want open press,â said one message.

At the roundtable in Iowa, the Iowa Farm Bureau president and several farmers opposed to the water rule got invites. In South Carolina, some media was allowed into a meeting dominated by interests opposed to the water rule, including the state Home Builders Assn., the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce, the South Carolina Golf Course Assn. and the state Farm Bureau. In Minnesota, Pruitt went straight from a visit with the governor to the offices of the agriculture industry association AgriGrowth, where he presided over another roundtable.

EPA officials said in a statement that information from the roundtables will ultimately be uploaded into the public docket. They did not specify what information that would include or when that would happen.

The agencyâs caginess has drawn an onslaught of open-records lawsuits seeking basic information about who EPA officials are meeting with, when, and what Pruitt is saying in his many invite-only discussions with industry groups and conservative think tanks.

âOne of the tragedies of this administrationâs approach is that it is just enhancing mistrust of what government is doing,â said William Ruckelshaus, who demanded full transparency of all such agency meetings when he ran the EPA during the Nixon and Reagan administrations.

California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra expressed confidence during a visit to Washington this week that Pruittâs rollbacks of policies like the clean water rule are so tainted by conflicts and legally troublesome administrative shortcuts that they will collapse in court.

The challenges Pruitt confronts include explaining the reams of data the EPA had compiled indicating that the economic benefits of keeping pollution out of the disputed streams and wetlands far outweigh the costs to farmers, developers and other business owners. The Obama rules were grounded in 1,200 scientific studies and 400 listening sessions over a period of years.

Longtime EPA staffers were stunned when political appointees at the agency last year directed them to write in a key report that protecting wetlands, intermittent streams and vernal pools would not bring any economic benefit to anyone. A detailed EPA analysis had already found that up to $500 million in benefits would be reaped by a range of interests, including commercial fisheries, recreational outfitters and drinking water utilities.

âWe were told to just drop the benefits,â said Betsy Southerland, who resigned her post as director of science and technology at the EPA Office of Water in August. âThey told us verbally, so they wouldnât have a written record of it.â An EPA spokesman downplayed the importance of the study, saying it was not required to rewrite the water rule.

Yet Pruittâs allies in Congress are clearly concerned the effort to unravel the Obama rule will falter. They are advancing a measure that would exempt the rollback from many of the public disclosure and other rules that apply to major regulatory changes.

The battle is being watched closely in California and the Southwest, where much of the water supply is linked to seasonal bodies of water and wetlands that would lose federal protection under Pruittâs vision.

âThe drinking water 1 in 3 Americans consumes is linked to these types of streams,â said Ken Kopocis, who was the chief EPA water official under Obama. âIn California, it is the water that comes down from the mountains from the snow and rain. If the streams up in those in hills are no longer protected, you can pollute those waters free from any federal Clean Water Act responsibilities and it will end up in these reservoirs. It applies to all these feeder streams, whether in Montana or Nebraska or Ohio. This water gets captured and used by 117 million people.â

âHow do you maintain a healthy ecosystem if you destroy those feeders?â he said. âYou simply canât.â

In some states, lawmakers are moving to backstop the protections as best they can. California is particularly energized. In others, they are eager to see the rule disappear, amid a vocal organizing effort by the industries that align with Pruitt. Farmers, ranchers and homebuilders complain the rules expose them to all manner of liability. They say filling a drainage ditch or a puddle on their property could draw costly EPA enforcement actions against them under the Waters of the United States rule drafted by Obamaâs EPA.

Pruitt complained of overzealous puddle and ditch enforcement in the Cattlemenâs video.

Itâs a point of view that is not necessarily shared widely in his own agency.

âWe are not running around regulating ditches,â said Jessica Kao, who recently left her post as the EPAâs lead Clean Water Act enforcement attorney in the Southwest. âThat whole argument is a red herring.â

Follow me: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.