My family left South Korea when I was 5 for AsunciĆ³n, Paraguay, and thatās where I first attended school.

Just as I was feeling somewhat comfortable speaking Spanish, the language changed again in fourth grade to English when we moved to Los Angeles.

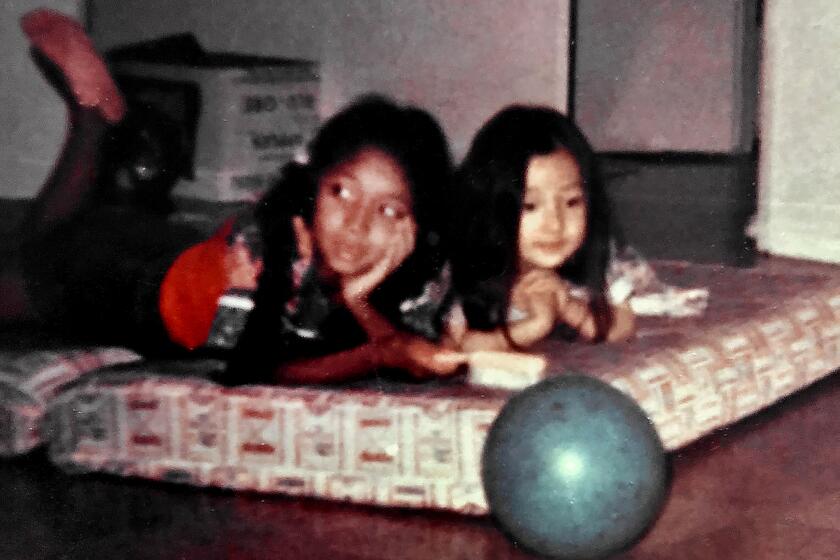

The fallout from the L.A. riots 30 years ago had a splintering effect on my Korean-Black family and on my cousin and me. Our relationship never healed.

Los Angeles has been the only place Iāve ever called home in my adult life. The city taught me how to survive alone, invisible, nameless. It made me go deep within myself, to speak to blank pages because it was too vast outside for anybody to hear me.

I found my voice as a poet, but I never quite shook that lonely immigrant kid that I had been. I kept people at armās length. Coming back to L.A. this summer from Pittsburgh, where I have been living for the last few years, and teaching young writers helped me heal those scars by doing what we donāt do enough in this city: building community.

āSo lonely you could dieā isnāt just a song lyric. Neurogenomics is proving that the human nervous system is not well suited to isolation.

Growing up in Koreatown in the 1980s, I learned not to expect friends to stay around. It was a transitional space, where immigrants landed until they could afford to buy a house in the suburbs. I learned to not allow new people to get too close. The city felt like it was getting bigger and bigger, the sprawl spreading as far out as the freeways would let it.

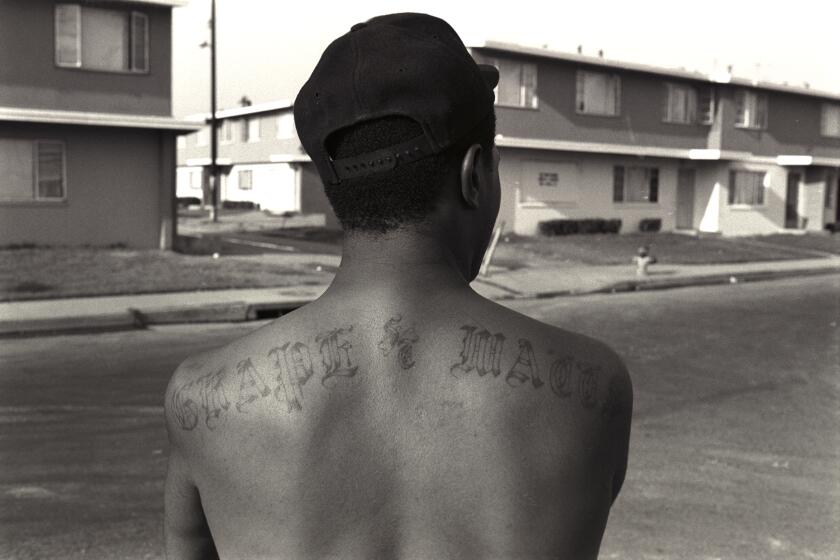

School was a struggle. Iād become afraid to speak because I thought nobody would understand my broken English-Korean-Spanish. I was also convinced, as I imagine many immigrant kids were, that if anybody found out I didnāt understand things, my family would be deported or imprisoned. In the ā80s, as police helicopters often hovered above our neighborhood while the crack epidemic peaked and the Bloods-Crips conflict was in full force, the only thing I was sure of was that I had to hide.

Days before the 1992 L.A. uprising, Crips and Bloods took a stand for peace.

L.A.ās roughness created more divisions. My sixth-grade teacher ridiculed me for not knowing how to speak English or Korean. In junior high, I almost caused a brawl between some gangs, the Korean Killers, who wanted to kill me for not speaking Korean well, and the MansField Gangster Crips, who were the only kids who accepted me. In high school, I attempted suicide.

Later, when I moved to New York for graduate school, everyone in L.A. was worried that I didnāt have what it would take to āmake itā there. But New York was the easiest place Iād ever resided. My wife, Judy, whom I met there, used to say how even on the roughest days, there was this sense that the momentum and energy of the city would carry you through. For better or worse, there would be people around you constantly moving.

Los Angeles is different. You can live and die alone. We often talk about how isolated one can be in L.A. ā in your home, in your car, in your own pocket too long of a drive away from anybody you know.

In my childhood, when even Koreatown was barren of pedestrians, the neighborhood would be pierced with gunshots, only to return to silence within seconds. I walked block after block without a person in sight, alone in a vastness Iād never known before Iād moved to the U.S., and it made me believe that any footstep near me was danger.

The season of the Jewish High Holy Days commands us to be together, just one way that our faith can help those who are struggling to reconnect with their larger communities.

In L.A., unlike New York City, you had to generate all the energy on your own. Through my poetry, I found a space where I could express myself. It made me feel less afraid to speak, and thanks to a teacher who told me to just write like I speak, I focused on distilling my feelings and experiences to the point where my small vocabulary was still enough to let out what was previously trapped inside me.

This summer, I taught poetry at California State Summer School for the Arts, a monthlong arts camp for teenagers. Old anxieties started building. When I saw other teachers and their pages of planning and curriculum, I was right back in that place from my childhood ā clueless at school and once again having to pretend I knew what I was doing.

I encountered so many young people there, the ālittle weirdosā as they coined themselves, seeking a like-minded tribe. I saw other kids still isolated and struggling.

But I wanted so badly for the teens to be supportive of one another. Of course, I was really talking to myself, to that younger version of me, wanting that version of me to experience a different childhood.

I decided to have each student give a positive comment to the person who read before them, and leave out criticism and editing suggestions. I told them it was more important to create a safe and joyful space for all of them to write, unlike typical writing workshops where people burn one anotherās work, and maybe only one or two people come out with a great poem.

The students jumped in. Inspired by our study of the poets Franny Choi and Danez Smith, they formed their own poetry group, the 309 Collective. And they vowed to support one another through high school and college, and even onward as they publish their first books. They promised to help other young writers feel less alone, less lost. In them, I saw the childhood and community I never had. There were a few moments when I grieved for my teen self, but that dissipated as they showed me beautiful glimpses of what life could be for them.

L.A. is my home, always will be. But the city never stops reminding you that you are making a life in the middle of the desert. It has been beautiful and brutal. Without a proper chosen family surrounding you, you can find yourself walking endlessly alone through unforgiving dunes.

Chiwan Choi is the author of āmy name is wolfā and founder of Writ Large Projects.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.