Opinion: Race matters when it comes to staying cool in Los Angeles

Heat has been in the headlines again and again this summer, with climate scientists predicting 2023 will be Earthâs hottest year on record.

Itâs not a one-summer event. As Daniel Cayan, a research meteorologist with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, told The Times: âThe extreme warmth that we see this decade is going to become more commonplace.â

The increasing heat waves are also getting hotter and lasting longer. Anyone exposed to extreme temperatures will be at high risk for heat-related illnesses, such as coronary, respiratory or renal failure.

And while itâs true that heat hits us all hard, itâs becoming clear that itâs Latinos and Black people, and those with lower incomes, who live closest to the boiling point.

California has some tips that would improve President Bidenâs climate investment Justice40 program.

A recent study in the journal Earthâs Future found that neighborhoods with more people of color and lower income people âexperience significantly more extreme surface urban heat than their wealthier, whiter counterparts.â The disparity can be deadly: Where itâs hottest, hospitalizations and fatalities skyrocket. Families already struggling to survive must sacrifice precious income to take time off to avoid the heat or to pay heat-related medical expenses. Their children may miss valuable developmental milestones because the local schools put hot weather closures into effect.

The study looked at summertime temperature peaks and census data in 1,056 U.S. counties that included about 90% of the nationâs population. In 75% of the sample counties, the researchers found significantly higher heat and daytime temperatures in low-income neighborhoods, with higher percentages of Black and brown residents, compared with moderate- or high-income and whiter areas.

What may be surprising for some is that in 71% of the counties that were studied, racial disparities in heat persisted even when the researchers controlled for income. Race alone matters in who gets shade and respite and who suffers the worst effects of our increasing climate crisis.

Iâve taken to walking in the early mornings when extreme heat makes it impossible to do otherwise.

The pattern repeats in Los Angeles. An analysis by UCLA found that during heat waves between 2009 to 2018, residents of working-class San Fernando Valley city of Pacoima â which is majority Latino and Black â made more than 19,000 excess emergency room visits. Thatâs seven times the number made by mostly white residents of beach-side Santa Monica.

The best hope for turning down the temperature for those who suffer most from the higher temperatures is to speed up investment in low-income communities and communities of color closest to the harm.

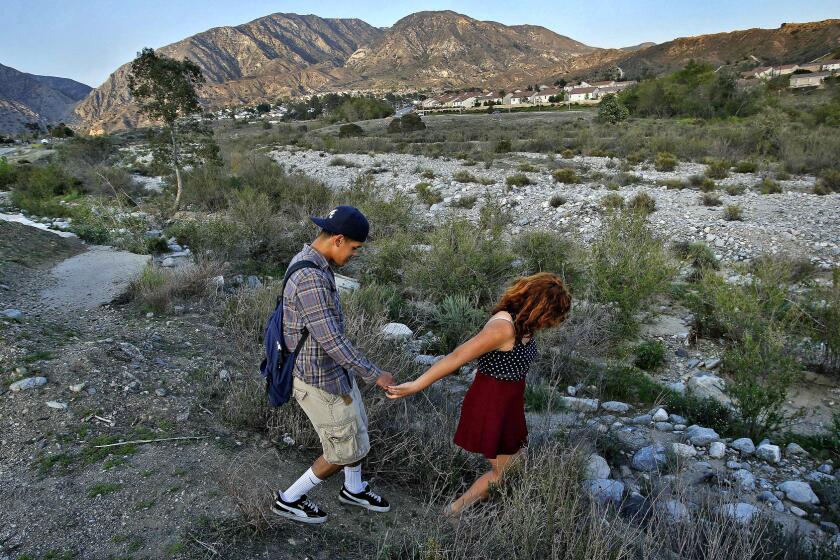

Just last month, the environmental justice organization Pacoima Beautiful hosted an event launching the Greening Americaâs Cities initiative of the Bezos Earth Fund. The ambitious $400-million program will expand access to parks, trees and community gardens in five cities, including Albuquerque, Atlanta, Chicago, Wilmington, Del., and Los Angeles. For Pacoima, the fund will provide $3.5 million to create a greenbelt and a walking path, with a less heat-absorbent surface, along the now-concrete embankment of the Pacoima Wash, providing a safer, cooler place for biking, walking and outdoor exercise.

California has some tips that would improve President Bidenâs climate investment Justice40 program.

Pacoima is never going to have the cooling effect of an ocean next door, but it can get relief regardless.âThis heat injustice is not OK,â said Veronica Padilla, Pacoima Beautifulâs executive director. âOur communities deserve the same opportunities and protection from heat disasters as communities like Santa Monica â more green space and tree cover, cool roofs and pavements, and air conditioning for the renters who are the majority of our residents.â

At a national level, the Biden administrationâs Justice 40 Initiative â a commitment that 40% of all federal investments to address climate change should benefit disadvantaged communities â is a welcome step forward. Families from East Los Angeles to the coal regions of Appalachia could see billions in funding for more efficient energy sources, clean transit, affordable housing, workforce development and pollution cleanup. If implemented correctly â with real community input and oversight â Justice 40 could have an enormous impact on helping the United States to achieve its climate goals while creating jobs and addressing stubborn housing and environmental problems.

When Rosalinda Cardenas was a kid, her parents warned her often: Stay away from the Pacoima Wash.

A collaborative web of local, state and national communities and organizations brought Justice 40 into being. The Equitable and Just National Climate Platform, for example, combined environmental justice groups with old-line national green activists to advocate for and develop the initiative. Similarly, it will take every mayor, senator and state representative â and all of our business leaders, educators and engaged neighbors â to demand that every neighborhood is equipped for a future of higher temperatures and higher risk.

The unprecedented âheat domesâ this summer are perhaps the best indicator that nature doesnât discriminate. And yet our societyâs deep-seated inequities magnify the assault of climate change on populations with the fewest defenses. That puts Pacoima and communities like it at the top of the list for solutions. We have to stay cool, all of us.

Bill Gallegos is the executive director of the Center for Earth, Energy and Democracy, a founder of the Equitable and Just National Climate Platform. Manuel Pastor is a sociology professor and director of the Equity Research Institute at USC.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.