Op-Ed: New test scores show students lost a lot of ground in the pandemic. Overreacting wonât help

Itâs bad news on the ânationâs report card.â To no oneâs surprise, this weekâs National Center for Educational Statistics report shows student achievement took a huge hit during the pandemic, with some test scores dropping to lows we havenât seen in 30 years.

Our youth are in a rough place. And it is easy to predict what is going to happen next. Politicians and cultural critics will demand schools go âback to basicsâ with long blocks of reading and math coming at the cost of science, social studies, arts, music and physical activity.

The pendulum will inevitably swing toward didactic âdrill and killâ teaching methods guaranteed to suck the joy out of learning for both students and teachers. And inevitably, the kids who will be hit the hardest are those at the least resourced schools.

But it doesnât have to be that way.

We donât have to use old-fashioned methods to address these new problems. This is 2022. After decades of research, schools have a tremendous number of new methods and techniques to bring to the table.

We know what works and what doesnât. We know what school administrators, teachers and youth need, and itâs not those old approaches. Instead, letâs use the best tools we have.

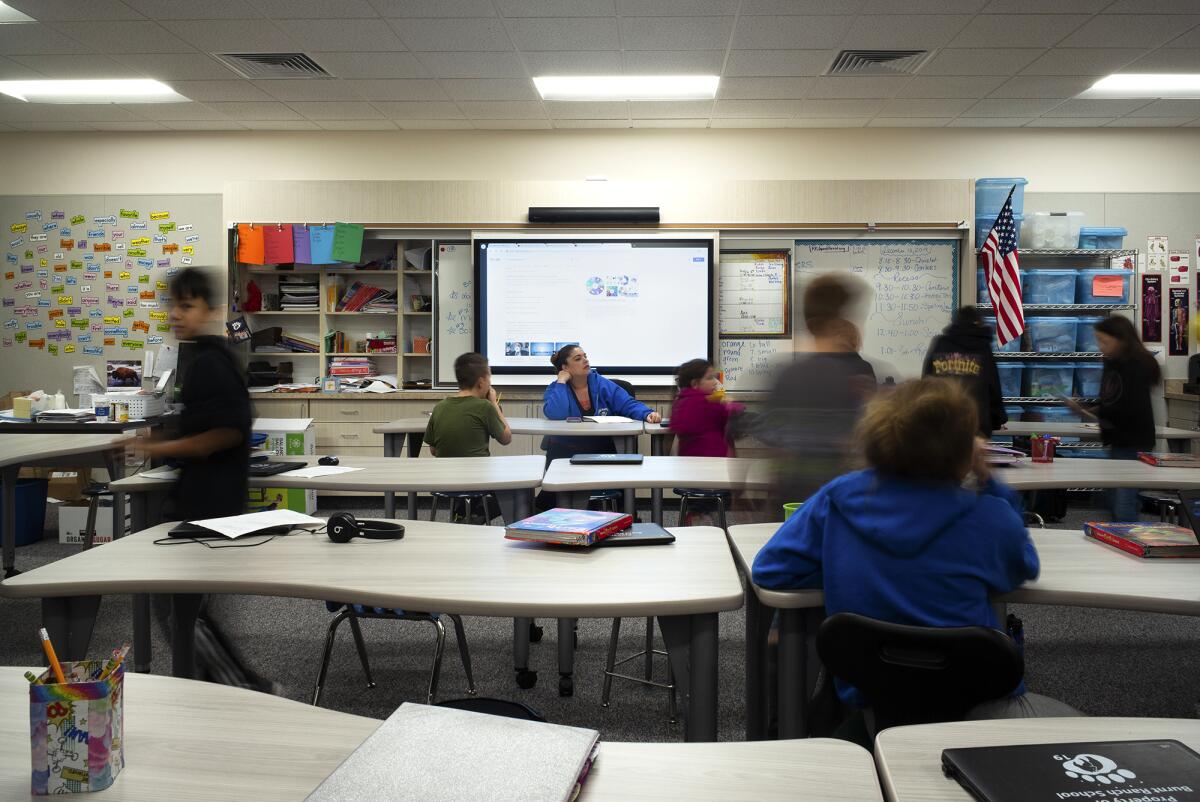

To move forward, letâs first remember: Relationships matter. Adults in school have tremendous power over whether kids are going to have a good or bad day. Teachers, administrators, counselors and others can make kids feel like they can do good work and that they matter. Or they can let students fall through the cracks. Schools can be intentional about how they organize routines and activities so teachers connect meaningfully with students and kids feel like they belong, giving kids a reason to come to class. If they arenât in school, they arenât going to learn.

The most promising practices create daily opportunities for small groups of students to meet with a caring adult. Elementary school class meetings offer a chance for children to be social with one another and for teachers to get to know individual students and be attuned to their needs and interests. Small-group interactions for middle and high school students can give a sense of purpose and make them feel known. If done well, teachers can use these activities to convey high expectations and respect for each student.

Effective teachers signal that they care for their students, notice their studentsâ strengths, recognize them for who they are, give them detailed feedback to help them learn, and care that they showed up. We have plenty of evidence that these practices work.

Assessment is also going to be key to recovery. We have spent the last two decades improving and honing how we assess studentsâ academic progress. Instead of a simple pass or fail, tests can now pinpoint what students know and donât, so teachers can see what they need to emphasize. By identifying gaps in knowledge, schools can adjust instruction and create tailored one-on-one and small-group tutoring experiences. For instance, if fifth-graders are learning the addition and subtraction of fractions but still do not know whether one-half or five-eighths is larger, there is specific personalized instruction that needs to happen.

Also, at a time like this, we canât just think about academics, but also must consider a childâs social and emotional skills and well-being. Itâs a good time to ask about our long-term goals for children and youth. In the 21st century, kids face an increasingly uncertain future. Itâs not just about learning, but also about using new knowledge to work with others to address real-world problems in their communities and beyond. Project-based learning and service-learning opportunities provide rich opportunities to learn and practice social and emotional skills while developing a sense of purpose and agency.

And letâs not forget the teachers and school leaders, who are stressed, anxious and burned out. They need our backing to do their emotionally demanding work. We must support their professional growth by making sure they have up-to-date materials and training. It also means increasing breaks during the day, offering assistance for menial work and giving teachers autonomy. Teachers canât engage kids in the exciting process of learning if they are rushed through the dayâs lesson, chasing unattainable goals.

After more than two years of COVID, school experiences have been scattered

and chaotic. Every teacher can tell a Zoom education horror story. Enrollment has dropped, with 1.3 million students leaving the educational system completely. Among kids who stayed, weâre starting to see how academic achievement has, predictably, suffered.

But a report card doesnât tell the whole story. Kids didnât stop learning during the pandemic. They learned how to adjust to unpredictable circumstances, manage chaotic and disruptive experiences, sustain friendships despite distance and master new technology. We can help them realize all theyâve learned through adversity. We can encourage them to use these new skills toward the classroom-based learning ahead.

If weâre innovative and can resist slipping back into outmoded methods, this is a chance for our education system to grow, an opportunity to make schools better than theyâve been.

Sara Rimm-Kaufman, a professor of education at the University of Virginia, is the author of âSEL From the Start: Building Skills in K-5,â a guide to social-emotional learning for elementary teachers.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.