Op-Ed: Monkeypox is not the next COVID. But itâs spreading from the same failures

The recent discovery by Stanford scientists that wastewater in Palo Alto, Sacramento and other cities in the Bay Area contains monkeypox DNA means that the outbreak has gained traction in California, where Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a monkeypox emergency on Monday.

But the wastewater discovery does not mean that monkeypox virus is spreading in water, in the air or widely enough that we are looking at a second pandemic at a time when weâre still struggling, as a nation and species, with SARS-CoV-2.

That doesnât stop panic on social media or in other corners of misinformation. Rumors posted on Twitter suggest children exposed to rat feces in their kitchens will be next to contract monkeypox. Or that weâll contaminate our water systems, sewer rats will become infected and the result will be an endless, uncontrollable pandemic that can infect and kill our children.

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency in California over the spread of the monkeypox virus in order to âbolster the stateâs vaccination efforts.â

Those scenarios arenât remotely likely. Monkeypox doesnât spread in water; people donât catch it from rodent feces. Itâs a well-studied disease: In the past, it has been concentrated primarily in rural West or Central Africa and transmitted from a bush animal to a person, who then would spread it to limited family members in close contact. During the 2003 outbreak in the U.S., people caught it directly from pet prairie dogs that got infected by small mammals imported from West Africa. None of the U.S. cases that year spread to another person.

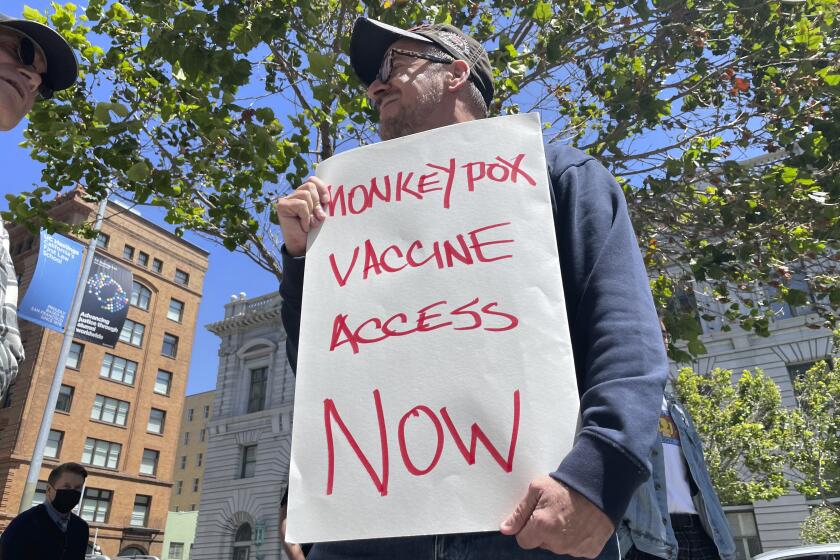

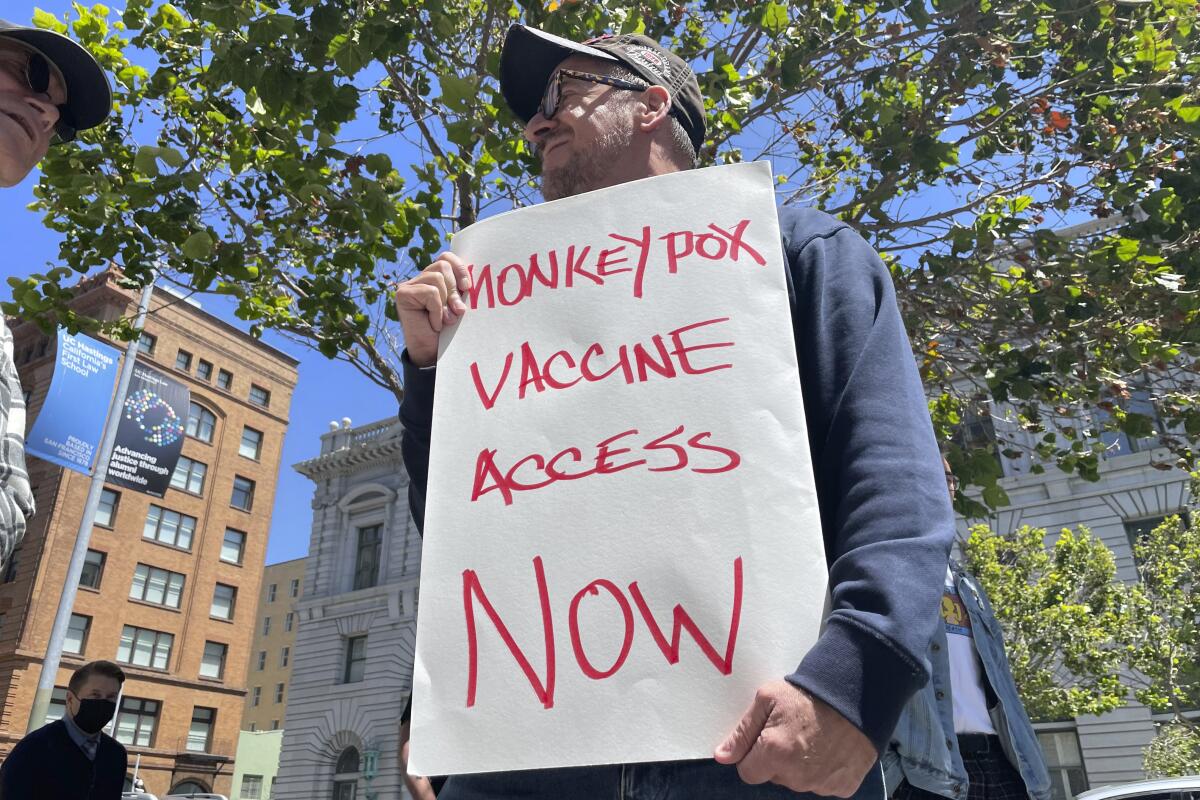

In contrast, the recent outbreak is spreading more widely person-to-person. But if governments take the right steps and help block transmission by giving key resources to those most at risk â currently gay and queer men â monkeypox can be contained. The global alarm sounded on this virus should be a warning to intervene now while the disease is manageable and take steps to limit future outbreaks, two goals well within reach.

Monkeypox was first detected among monkeys kept in a Denmark laboratory in 1958. Only in 1970 did doctors record a human case, indicating that monkeypox could also infect people. The disease, which closely resembles smallpox, wasnât distinguished as a separate infection until smallpox was nearly eliminated. Smallpox vaccination campaigns kept both diseases at bay until 1980, when the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated and vaccination campaigns ended.

The difference between the two diseases, however, is critical: Smallpox spread only through humans, with no animal population keeping it alive. It evolved over millennia to become a true human specialist, effective at transmission and overcoming immunity. Centuries of an arms race in Africa, Asia and Europe allowed the smallpox virus to fine-tune its attacks on the human immune system. When it burst into the previously unexposed populations of the Western hemisphere via European invaders, the sharpened teeth of smallpox met no resistance. Some scholars estimate that 90% of Native Americans died of it.

We have tools to fight this crisis, but public health and medicine are hampered by systemic bias.

Monkeypox never spread among people as efficiently as smallpox did. Itâs not impossible that it could adapt, over a long time, to do so. But orthopox viruses such as smallpox and monkeypox are DNA viruses, making them far more stable than the single-stranded RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 and influenza and therefore much slower than those viruses to adapt to a new host. Though scientists have observed genetic changes in monkeypox during this latest outbreak, no one knows what â if anything â those changes mean.

That monkeypox is spreading rapidly is undeniable. While monkeypox isnât at this point a truly sexually transmitted disease like gonorrhea or syphilis, sexual contact has driven this outbreak. Monkeypox spreads through intimate physical contact, including direct contact with monkeypox pustules loaded with virus. People may not realize that their malaise is monkeypox in its early phase. Although anyone touching an infected person or their sheets, clothing and towels could theoretically catch monkeypox, the highest risk remains in concentrated networks of friends, companions and lovers.

That means the public health response should focus on those networks, who are most at risk and so need the most protection. According to a recent World Health Organization report, about 99% of cases outside Africa have been in men and 95% involve men who have sex with other men. Gay men and LGBTQ communities especially need clear guidelines about how to recognize early symptoms â headaches, swollen glands, fever, sore throat â as well as ready access to vaccines, antivirals and, crucially, government benefits allowing them to isolate at home until theyâre well.

The scandal of monkeypox is that this worldwide outbreak has happened at all. An epidemic has persisted in Nigeria since 2017. A more deadly strain has caused thousands of suspected cases and likely killed hundreds in the Democratic Republic of Congo. At least eight people have died in the current outbreak.

We have for years had the capacity to vaccinate those most at risk via two doses of Jynneos, the safer, updated version of the old smallpox vaccine. But we havenât done so, and now the virus has reached the Western world. Now millions of doses have been ordered for the U.S. alone â and none yet for Africa.

Why do we in the West only pay attention when a disease outbreak directly threatens us? Thatâs the real outrage, the real question. The only answer is a more global approach to health, a recognition that when disease breaks out in one part of the world, it often will â as COVID and now monkeypox have shown us â affect us all.

Wendy Orent is the author of âPlague: The Mysterious Past and Terrifying Future of the Worldâs Most Dangerous Diseaseâ and âTicked: The Battle Over Lyme Disease in the South.â

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.