A heavy price for cheaper drugs

You get what you pay for. This maxim is proving true all over again when it comes to steroid injections used to alleviate back pain. Making safe and effective versions of such drugs involves manufacturing steps that arenât trivial. The cost of the medicine has to match the care that goes into creating it and the oversight required to ensure that the standards are maintained.

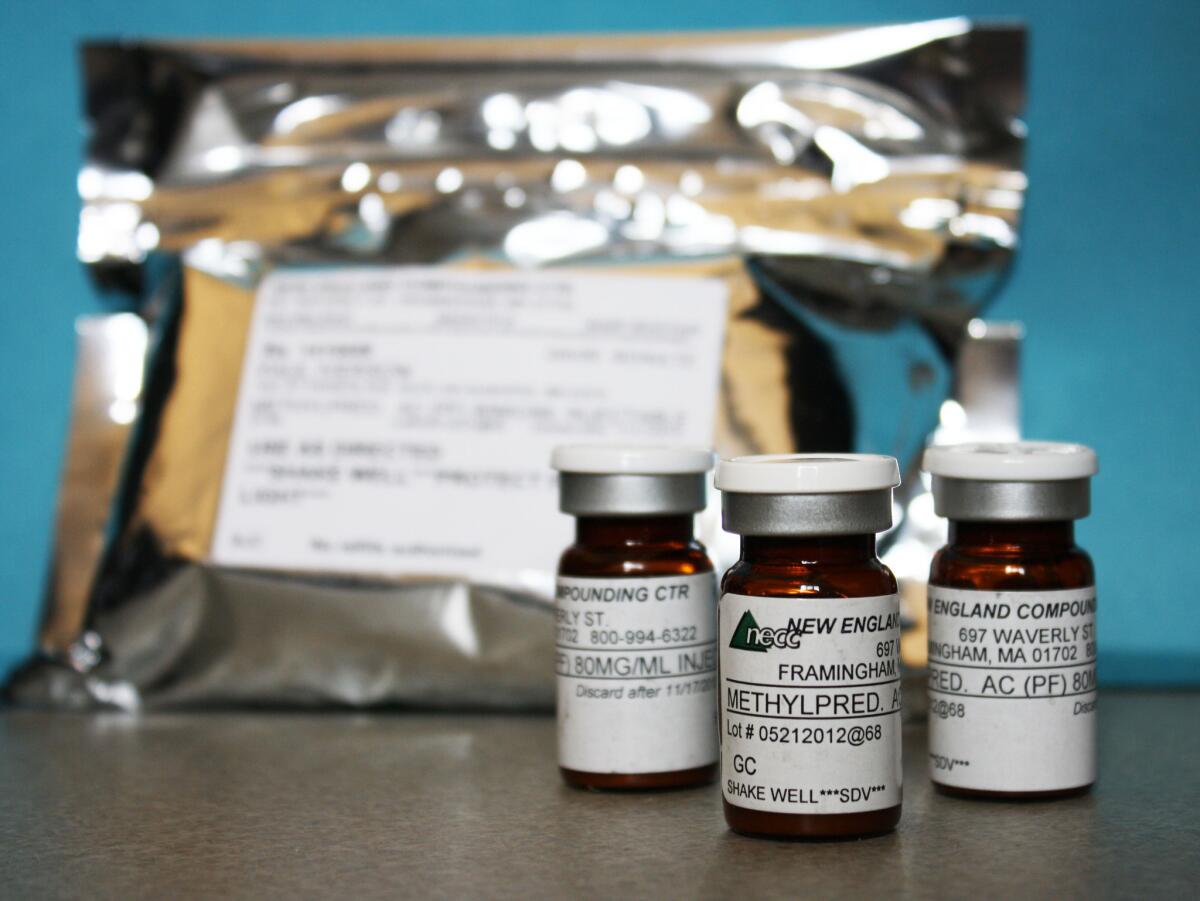

Since September, about 250 people have been sickened and 19 have died after getting steroid injections for back pain. They came down with a rare form of fungal meningitis that has been traced to tainted vials of the steroid shots. The injections have been linked to a compounding pharmacy in Massachusetts.

Compounding pharmacies are licensed by states, typically with little oversight by the federal Food and Drug Administration. They are supposed to exist to create customized drugs to fit the unique needs of individual patients. They are called upon to fill a prescription for a specialized dose of a drug or to provide patients with a customized medicine that is not produced by the big drug companies. Compounding pharmacies that do their job well fill an important role in clinical medicine.

The Food and Drug Administration has âguidanceâ in place regarding compounding pharmacies: These businesses cannot mass produce drugs or widely distribute them across state lines unless the shipments are fulfilling prescriptions doctors wrote for individual patients. But the agency doesnât have the funds or personnel to enforce the rules. The compounding pharmacy implicated in the meningitis outbreak has recalled more than 17,000 individual vials of injectable steroid that were sent to 23 states, and it had been warned about unsafe manufacturing conditions in the past.

Lax rules and oversight mean that compounders can undercut costlier versions of the same medicines made by major drug manufacturers that are subject to strict FDA standards. The difference can be tens and sometimes hundreds of dollars for some prescriptions.

Our penchant for greater assurances of safety tends to run headlong into our desire to keep costs down (and into lobbying efforts to keep compounding pharmacies relatively regulation free).

In 2003, Congress considered establishing an FDA committee to oversee compounding pharmacies, and in 2007 a Safe Drug Compounding Act was introduced, but the industryâs trade association and individual compounders stopped the efforts. There was worry about ânegatively impacting patient accessâ to necessary compounded medications, according to a Reuters report on the lobbying effort.

Access is often a matter of cost. For years, women used a compounded version of progesterone to prevent premature delivery during pregnancy. But once a manufacturer, KV Pharmaceuticals, got the nod for an FDA-approved form of that medicine, FDA policy was to clear the market of compounded versions that were being produced in bulk â from cheaper and sometimes questionable ingredients â and then widely commercialized. One of the compounding firms making the progesterone drug was the same outfit behind the tragedy with the steroids.

But when the FDA went to step in, according to media reports, senior Obama administration officials grew concerned about the much higher price of the FDA-approved progesterone â one report said doses went from $25 to $1,500. The FDA stepped back, announcing that it would exercise âenforcement discretionâ with regard to compounded versions of the drug. Meanwhile, KV Pharmaceuticals, which invested in FDA approval of its version of the drug, is now in bankruptcy.

This kind of focus on cost over assured safety sends a mixed message to would-be violators that rules wonât apply so long as the price is right.

To be sure, the FDA must also address its role in driving up the cost of the safe manufacture of drugs. Drug companies complain that the agency doesnât support innovations that could make manufacturing more efficient. And one reason the compounded steroid injections were in high demand is that the only two FDA-regulated drug companies that produced generic versions of that medicine had to close their plants when the government suddenly changed the standards they had to meet.

The investigation of the deadly meningitis outbreak has only just begun. There are already calls on Capitol Hill to arm the FDA with more authority to regulate compounding pharmacies. New laws merit consideration, as does improved enforcement and coordination of the federal regulations and policies that already exist. But we also need to have the will to see them through: The costs of drugs will inevitably rise in tandem with added scrutiny. You really do get what you pay for.

Scott Gottlieb is a physician and resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was the FDA deputy commissioner from 2005-07. He consults with and invests in branded drug companies.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.