Opinion: We can learn from the Orlando attack, but only if we’re willing to be brave

- Share via

This week, 49 people were killed and 53 were injured by a gunman in an Orlando, Fla., nightclub. As reporters, we’re compelled to think and write through even the moments that stun us. The Los Angeles Times comes out on paper every day, and updates online minute by minute. On several occasions this week, I became absorbed in other work and briefly lost myself in the moment. But it always came back in a crush of rapid-fire questions, each of which had the same answer. Why am I so anxious? Orlando. Why am I nauseous? Orlando. Why am I so angry? Orlando. Why am I anguished? Orlando.

This anxiety is simultaneously broad and specific. The first time I felt afraid of being shot was when I saw “Inside Out” in the movie theater. The movie was released within a few weeks of the 2015 shooting in Lafayette, La., where a gunman killed two people and injured nine others, then killed himself. As we settled into our row, I thought for the first time, “I could die here.” I didn’t tell my family; I ate popcorn and Twizzlers and acted like a normal person, like a person who didn’t live in a country where there were people who shot strangers in the head while they were watching movies. Like a person who didn’t live in a country where the government was unwilling to restrict the sale of or access to the guns those people used.

There are other Americans who are not afraid of guns: who use them to hunt or take them to shooting ranges, who lock them safely away, who are well-trained in how to use them. Those people are not the people I fear.

I’m white and straight and grew up in a tiny town. So it took until my late 20s to fear seeing a loved one shot, or being shot myself, and to wonder if I’d freeze or run. For many Americans, those questions come earlier. Those who grow up in neighborhoods with concentrated gun violence, or who belong to one or more minority groups that make them vulnerable to hate-based attacks, know this low- or medium-grade fear as a baseline. It can be triggered to greater degrees, but is never absent.

We need long, clear memories, as well as the bravery to stay with the pain of this moment and, this time, not move on.

Psychological research shows that racial minorities are less likely to seek treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder than white Americans. This may be because minorities have become so used to being attacked that they don’t identify the traumatic stress they’re forced to carry as a psychological affliction, but as an inextricable piece of what it means to live as a targeted person. Last year, Claudia Rankine wrote a brilliantly reported essay for the New York Times, “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning.” “The Charleston murders alerted us to the reality that a system so steeped in anti-black racism means that on any given day it can be open season on any black person — old or young, man, woman or child,” Rankine wrote. “There exists no equivalent reality for white Americans.”

Extending her concept, there also exists no equivalent reality for straight Americans; they can’t know the compounded trauma LGBT people absorb from seeing violence constantly perpetuated against their communities. There exists no equivalent reality for Christian Americans; they can’t know the trauma that many religious minorities absorb from seeing violence constantly perpetuated against their communities. I have every reason to believe that I am unlikely to be targeted for violence, and yet the fear of violence is part of my life’s fabric. I can’t begin to imagine the depth of pain or fear the LGBT community has felt this week, that black Americans felt after Charleston. I can’t, and I never will.

If you’ve seen “Inside Out,” you know that it’s an animated film about what happens in a little girl’s brain. It’s both reductive and profound in its simplicity. The girl has five anthropomorphic emotions that battle for her attention: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust. After I saw the film, I thought about what single emotion I might have added, and came to Grief. Of course, grief is difficult for children to understand. It becomes easier as you grow older.

Grief doesn’t blanket each moment, but it hangs around us. How can we live like this, I find myself wondering. Last year, I saw a woman taken away in an ambulance because her grief for her slain brother was shutting down her body. In moments like that, I hear only the absence of an answer: I’m not sure, I’m not sure, I’m not sure. I’m not sure how we live with Sandy Hook, with San Bernardino, with Aurora, with Orlando, with the 135 other mass shootings that have taken place in the first six months of this year.

This week, the Editorial Board wrote about the gun control measures that Democrats filibustered over in the Senate, and opined that our national failure to address gun violence in a meaningful way is one of the embarrassments of our age. The board addressed Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim hate mongering and the consequences of language in the wake of the attacks. The Times ran opinion pieces on the importance of listening to LGBT perspectives on the attack, and the endemic violence that the LGBT community has been subjected to. The paper’s news desk covered Orlando exhaustively.

Columbine was 17 years ago. We try to be hopeful. We’ll try again next week. This is why we’re angry.

In the wake of the attack, Roy Guzman, a gay Latino Floridian, wrote a poem named “Restored Mural for Orlando.” It was gorgeous and shattering and made me shake. “I am afraid of attending places that celebrate our bodies because that’s also where our bodies have been cancelled / when you’re brown & gay you’re always dying twice,” Guzman wrote. This is why we’re anguished.

The Times has written about the need for gun control policies at length, and will continue to do so. But in order to get even the most moderate legislation passed, the movement for gun control begs for reserves of fury and compassion that are equal to our fear and grief. Forty-nine dead, 53 injured. This is why we’re anxious.

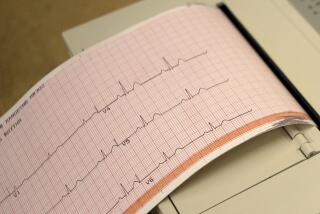

As these mass shootings happen more and more frequently — again, 135 from New Year’s to now — the dots get so close together that they begin to mesh into a single line, the shape of a heartbeat faltering and then failing. This is why we’re nauseous.

The grief we feel after a massacre like Orlando is a sharp expression of a subtler daily heartache: that which accompanies the knowledge that we didn’t stay vigilant enough or try hard enough last time. That we got back to the rest of our lives too quickly. That we wept, and felt things, and intended things, but failed to live up to them. If we could only sit in the knowledge that many of us had sworn, and sworn, and sworn to do all we could to prevent the kind of carnage like that which occurred in Orlando, it would be so excruciating that we would have no choice but to change. If there will ever be better policy on gun control, we need long, clear memories, as well as the bravery to stay with the pain of this moment and, this time, not move on.

ALSO

Readers React: After Orlando, who’s on autopilot — the president or his conservative critics?

Op-Ed: Why banning assault rifles won’t reduce gun violence

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.