Editorial: Motive is irrelevant when states make it harder for minorities to vote

A federal appeals court decision striking down parts of North Carolinaâs election law â including a photo ID requirement â is only one of several recent judicial rulings that have breathed new life into the Voting Rights Act and the Constitutionâs protections against abridgment of the right to vote.

But the decision is also notable for its recognition of an important truth: that a law that makes it harder for minorities to vote can constitute intentional racial discrimination even if it might be primarily motivated by a desire to achieve partisan advantage.

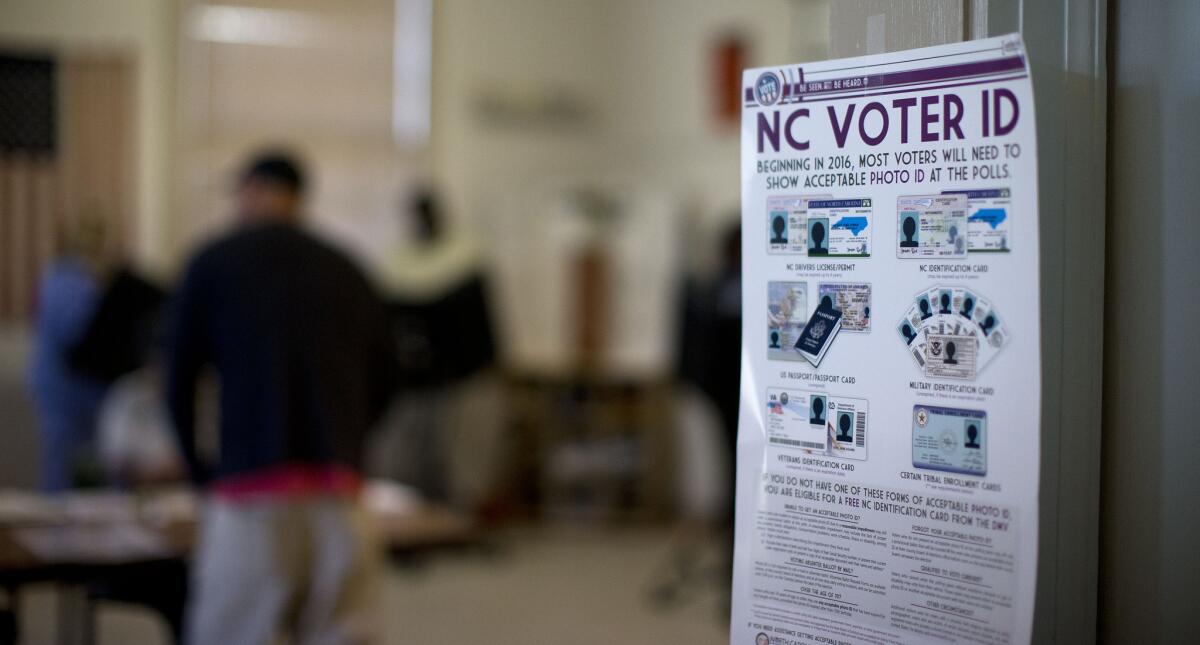

On Friday, a three-judge panel of the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals struck down several provisions of the North Carolina law enacted by the Republican-controlled Legislature, including a photo ID requirement, a cutback in early voting options and the abolition of same-day registration. The court found not only that those changes disproportionately made it harder for African Americans to exercise the franchise but also that the law was enacted with âdiscriminatory intentâ â a more serious indictment.

To a layperson, âdiscriminatory intentâ might suggest that the legislators who enacted the bill had to be driven by conscious racial prejudice. But it may be that in North Carolina, as in other states that have approved photo ID laws and other restrictions, the âproblemâ wasnât the votersâ race as such but the fact that minorities tend to vote Democratic. As a Republican leader in Pennsylvaniaâs Legislature indiscreetly put it in 2012: âVoter ID ⌠is gonna allow Gov. [Mitt] Romney to win the state of Pennsylvania.â

A similar motivation could explain North Carolinaâs law, which was passed after a 2013 Supreme Court decision freeing officials in North Carolina and other states with a history of discrimination from the obligation to âpre-clearâ changes in election practices with the U.S. Justice Department or a federal court.

As the 4th Circuit explained: âBefore enacting [the] law, the legislature requested data on the use, by race, of a number of voting practices. Upon receipt of the race data, the General Assembly enacted legislation that restricted voting and registration in five different ways, all of which disproportionately affected African Americans.â

The court found that the photo ID requirement disproportionately excluded African American voters.

The court found that the photo ID requirement disproportionately excluded African American voters because they were less likely to have the forms of ID mentioned in the law. And the elimination of one out of two days of Sunday voting affected African Americans because ministers at black churches sponsor âsouls to the pollsâ events, which transport worshipers from worship services to polling places.

As the court concluded: âUsing race as a proxy for party may be an effective way to win an election. But intentionally targeting a particular raceâs access to the franchise because its members vote for a particular party, in a predictable manner, constitutes discriminatory purpose.â

Although a state doesnât have to have a discriminatory intent to run afoul of the Voting Rights Act â which also prohibits laws that have a racially discriminatory effect â a finding of discriminatory intent gives the federal government additional tools to deal with unfair laws.

For example, if a state or other jurisdiction has been found to have engaged in intentional discrimination, a court can order it to âpre-clearâ future changes in its election practices. (In the North Carolina case, the appeals court declined to order such pre-clearance, saying that it wasnât necessary in light of its order to the state not to enforce the challenged provisions. But its definition of discriminatory intent is still important and could influence other courts.)

Itâs gratifying that the federal courts are taking a sophisticated view of what constitutes racial discrimination in voting (and scrutinizing claims that restrictions are designed to prevent largely imaginary voter fraud). But, welcome as such decisions are, they canât substitute for a new federal law that would once again require states with a history of discrimination to obtain prior federal approval of changes in their voting practices. Such legislation has been languishing on Capitol Hill; it needs to be a priority for the next Congress and the next president.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.