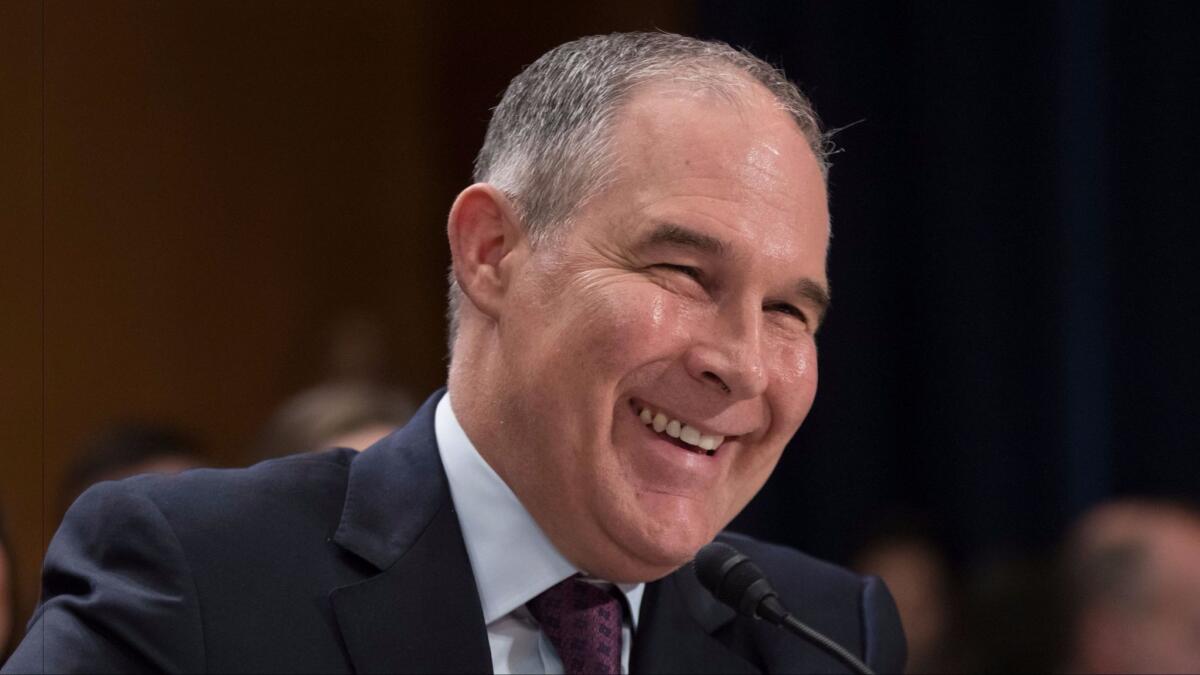

Editorial: Putting Scott Pruitt in charge of the EPA risks irreversible damage to the planet

As Oklahomaâs attorney general, Scott Pruitt has spent the last six years suing the federal Environmental Protection Agency over the extent of its authority, particularly its efforts to regulate the oil and gas industry and restrict coal-fired power plants. These industries belch out the greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming, yet Pruitt has led or been part of 14 lawsuits (most of them in concert with industry) challenging rules that limit them or otherwise protect the nationâs air and water.

Itâs hardly news that some public officials are shills or apologists for powerful polluting industries. But to select someone with a record like Pruittâs to lead the EPA is mind-boggling, offensive and deeply worrisome. The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee approved the appointment Thursday despite a boycott by Democratic members, but the full Senate should say no.

Yes, Trump won the election, and as president, heâs entitled to appoint people who reflect his political views. But when the presidentâs policies and appointees pose such a fundamental threat to the nation, even a Senate controlled by his fellow Republicans â whose first loyalty should be to the people of the United States â must put the nationâs best interests ahead of party loyalty.

[Pruittâs] appointment would be a classic case of putting the fox in charge of the henhouse.

Pruitt shares Trumpâs ignorant skepticism about the global threat from climate change. Like Trump, Pruitt disbelieves the scientific consensus that human actions play a significant role in heating up the planet and that a crisis looms. That alone disqualifies him from running an agency charged with protecting the environment â because if there is any single issue that poses an urgent threat to the planet in the century ahead, it is climate change.

In addition to his objectionable efforts to weaken the EPA, Pruitt is a key figure in a cabal of Republican attorneys general who sued to undercut the subsidies for low-income insurance buyers under the Affordable Care Act, to kill the Obama administrationâs Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, and to void the expansion of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. Those efforts suggest Pruitt is not a principled law enforcement figure so much as an ambitious partisan.

There is a legitimate philosophical argument to be had over the proper extent of federal regulations. But Pruitt wouldnât run the agency as just another small-government Republican interested in paring excessive limitations on business. He actually disagrees with the fundamental mission of the EPA. He has argued that the federal government should play a lesser role in environmental protection, and that primary control should be given to the states. This is wrong-headed. Putting West Virginia in charge of its coal industry or Texas in charge of its oil industry would lead to horrific environmental damage not just there, but in neighboring states downwind and downstream.

Pruittâs own performance in Oklahoma stands as evidence of this. When he first won election with the backing of the energy industry, he dissolved the officeâs environmental prosecution team and created what he called the Federalism Unit to âcombat unwarranted regulation and overreach by the federal government.â Pruitt testified in his confirmation hearing that his office handled 15 environmental protection cases, but critics in Oklahoma say he inherited a dozen of those from his predecessor.

Pruittâs political career in Oklahoma was heavily supported by the oil and gas industry. He submitted letters ghost-written by oil industry officials to the EPA, Interior Department and the White House challenging various regulatory schemes the industry opposed. He refused in his nomination hearing to promise to recuse himself from decisions tied to the lawsuits heâs involved with, and which he would now be responsible for defending. His appointment would be a classic case of putting the fox in charge of the henhouse. And he poses a particular threat to California: He has raised the possibility that his EPA could rescind federal waivers that Californiaâs environmental regulators have used to help cut greenhouse gas emissions from motor vehicles by nearly a third since 2009.

As reprehensible as most of Trumpâs actions and appointments have been so far, their broader consequences, for the most part, are reversible at some later date. (Although not for individuals, such as a refugee who gets killed because Trump sends him back to a country where his or her life has been threatened.) Putting Pruitt in charge of the EPA, however, poses an irreversible risk to the planet, and the Senate needs to ensure that doesnât happen.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.