Editorial: Measure JJJ could make L.A.’s housing crisis even worse. Vote no.

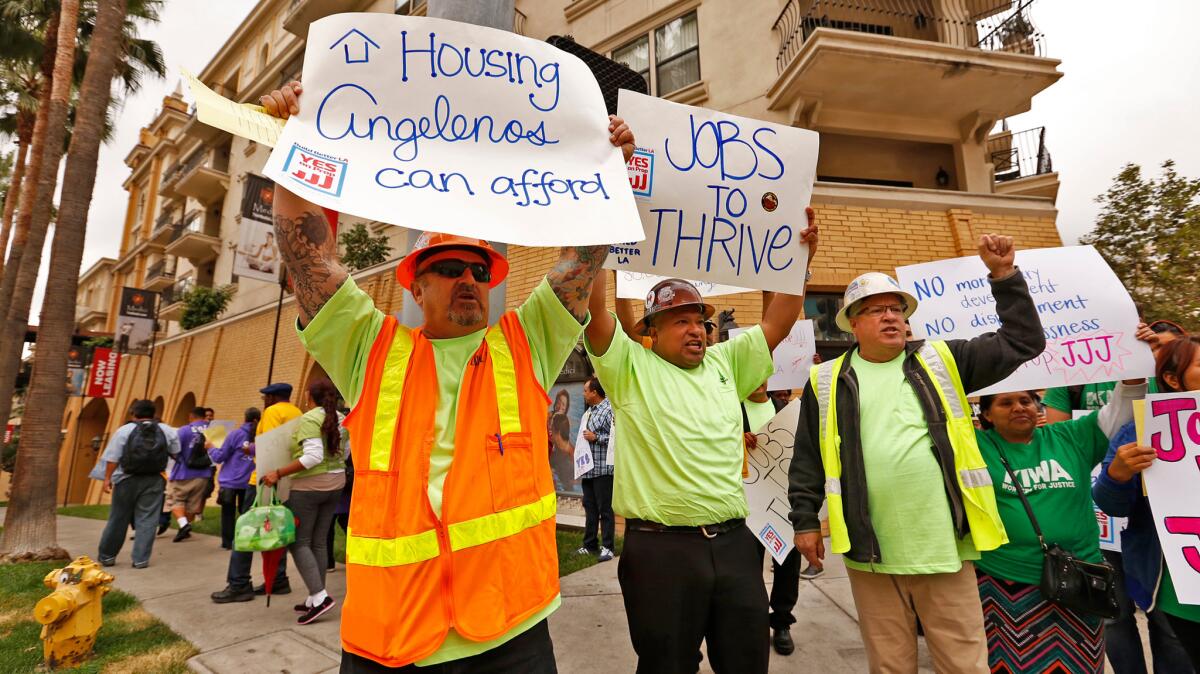

Measure JJJ on the November ballot purports to offer solutions to two of Los Angeles’ most challenging problems: How to create more affordable housing for the city’s poorest residents, and how to increase the number of good-paying jobs. Sounds like a slam dunk, right?

It’s not. Measure JJJ vividly illustrates why land-use planning by ballot initiative is so problematic. It was sponsored by the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, construction trade unions and affordable housing groups as the counteroffensive to the Neighborhood Integrity Act, a slow-growth initiative that would slap a two-year moratorium on major developments and require an overhaul of the city’s land-use plans. That initiative has since moved to the March city election, but Measure JJJ, also known as Build Better L.A., remains on the November ballot.

Measure JJJ would impose some of the nation’s most demanding affordable housing and wage mandates on privately-funded development. It was written without any analysis of whether the measure would actually relieve the city’s affordable housing crisis, as opposed to increasing the cost of new construction so much that developers build fewer units for low- and middle-income Angelenos.

Creating good housing policy means balancing how much the government can demand against how much the real estate market will bear.

Voters should reject Measure JJJ, knowing that there are two smarter affordable housing proposals currently being studied at City Hall. Mayor Eric Garcetti is championing a fee on new development to fund subsidized housing construction. And Hollywood-area City Councilman Mitch O‚ÄôFarrell proposed a ‚Äúvalue-capture‚ÄĚ ordinance ‚ÄĒ similar conceptually to Measure JJJ ‚ÄĒ that would require housing developers to include affordable units in their projects if the city allowed them to build taller or denser than the property‚Äôs zoning would normally allow.

Creating good housing policy means balancing how much the government can demand against how much the real estate market will bear. That’s why it’s much better to set these policies through study and legislation, rather than a one-size-fits-all ballot initiative.

Measure JJJ would apply to residential projects of 10 or more units that request a General Plan amendment, zone change or permit to build taller than allowed. Because L.A.’s plans are so outdated, many of the housing units built in recent years have required at least one of those land-use changes. To get approval, builders would need to meet new requirements on how much they can charge for their units, the wages they pay and the workers they hire.

Apartment developers would have to guarantee that up to 25% of the units they build would be affordable for low-income tenants. For condominiums and homes, developers would have to provide up to 40% of the units at rents affordable to moderate-income residents. They could also choose to provide the affordable units elsewhere, or pay into the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund.

Developers would also have to abide by several strict hiring mandates. For example, contractors would have to ensure that at least 30% of their construction workers live in Los Angeles, and that 10% live within 5 miles of the project and be so-called transitional workers, a category that includes the homeless, single parents, veterans and those lacking a high school diploma.

In addition, the contractors would have to pay wages set by the city‚Äôs Bureau of Contract Administration. The initiative doesn‚Äôt spell out what those wages would be, but builders fear they would be equivalent to the ‚Äúprevailing‚ÄĚ wages required for publicly funded projects that are often double or triple what non-union construction workers earn. For example, the median hourly wage for a carpenter in the Los Angeles region is about $24; the prevailing wage is about $55 an hour.

These wage and local hire requirements could make it considerably more expensive for developers to build housing in Los Angeles, which seems counterproductive in a city with so great a need. They would also set a worrisome precedent. It‚Äôs inappropriate for the government to step into the private housing construction market and set wages. Notably, the measure would allow the city to waive each of its mandates if they proved unworkable ‚ÄĒ except for the wage requirement.

The housing advocates behind Measure JJJ are understandably frustrated with city leaders who have failed for years to take any meaningful action to increase the supply of affordable housing or reform the city’s broken planning and land-use system to allow more construction of housing at all price ranges. Faced with public pressure and the threat of draconian ballot initiatives, Garcetti and the City Council are beginning to take the city’s housing crisis seriously. Hopefully, they are not too late.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.