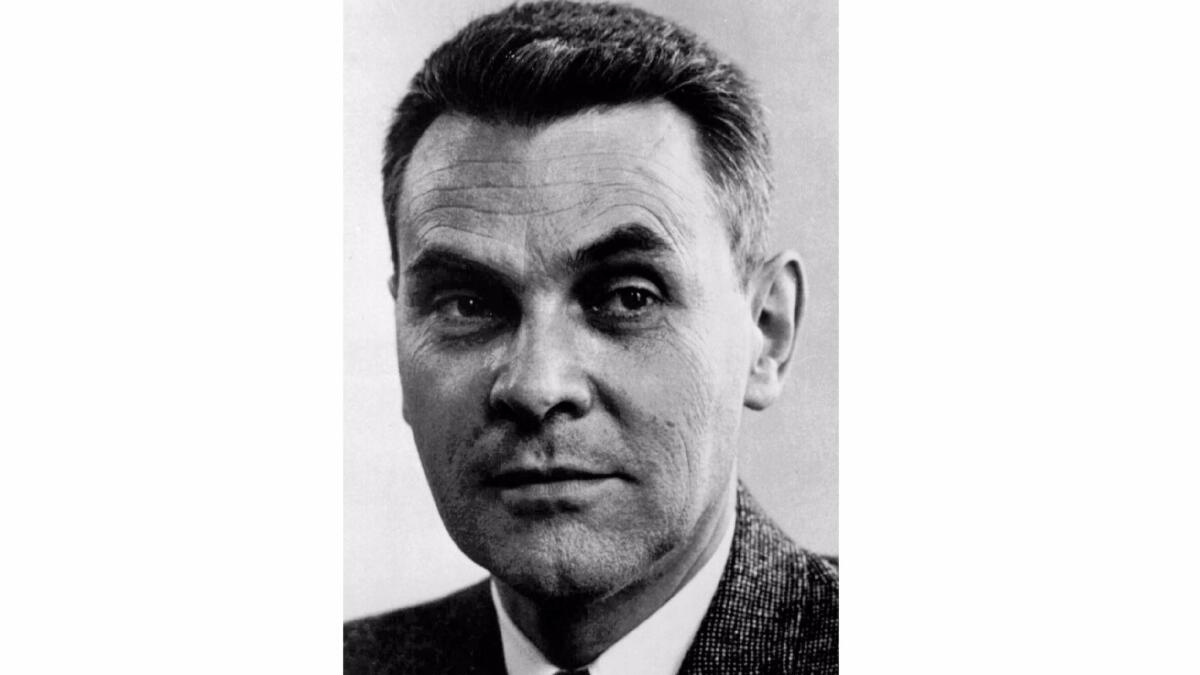

William H McNeill, prize-winning world historian, dead at 98

William H. McNeill, the groundbreaking scholar who wove the stories of civilizations worldwide into the landmark âThe Rise of the Westâ and described the power of disease to forge history in âPlagues and People,â died Friday. He was 98.

McNeill, who died in Torrington, Conn., wrote more than 20 books, notably âThe Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community,â published in 1963. The New York Times called it âthe most stimulating and fascinatingâ work of world history ever released. It won the National Book Award, sold well despite exceeding 800 pages and later was ranked No. 71 by the Modern Library among the 20th centuryâs best English-language nonfiction books.

McNeill sought new ways to explain the world. He didnât explore history through the feats of great men but through everyday innovations, contacts between civilizations, and disease. He investigated how such changes as better-designed plows or potato cultivation propelled human societies â and how pathogens defeated them. His books had sweep and brimmed with daring, provocative ideas.

He wrote âabout big topics, trying to speak to a bigger audience,â said Ian Morris, a Stanford University history professor.

Morris said McNeillâs writing was especially influential in places such as California, where few students identified with the traditional way of teaching history via âstraight-down-the-middle Western Civâ courses focused Great Britain and Europe.

McNeill painted history against a sprawling new canvas, demonstrating âthat there is this whole world out there â that you have to look at the world on a global scale and look at the different strands of history,â Morris said.

âAnd he was such an unusual guy, that was just the beginning for him,â Morris added.

McNeill had a knack for flipping conventional wisdom on its head and upending long established paradigms, as he did in his 1983 work âThe Great Frontier: Freedom and Hierarchy in Modern Times.â

It was published at a time when historians of the American West were just beginning to break free of the influence of Frederick Jackson Turner, who associated frontiers with freedom and opportunity, said Stephen Aron, UCLA history professor. âThat is the way the myth of the West has been told â âgo west for freedom,â â he said.

McNeill inverted this by suggesting that labor scarcity meant labor often had to be compelled in frontier regions, Aron said. Thus, frontiers tended to be areas of forced labor, McNeill argued â just the opposite of the mythology. His insights influenced a subsequent generation of scholars of the West, making them more attuned to âthe spectrum of unfree laborâ and the conditions under which it occurs, Aron said.

âThe Rise of the West,â even in its title, was a direct challenge to Oswald Spenglerâs âThe Decline of the West.â It also served as counterpoint to Arnold Toynbee, then the reigning scholar of world history. Toynbee believed that civilizations had essentially developed independently and their stories were separate. McNeill countered that they were very much part of one story.

âIndeed, world history since 1500 may be thought of as a race between the Westâs growing power to molest the rest of the world and the increasingly desperate efforts of other peoples to stave Westerners off,â wrote McNeill, who also cautioned that another civilization could yet overtake the West.

McNeill welcomed disagreement, and in a âretrospective essay,â he noted that âThe Rise of the Westâ was in part influenced by the Cold War and the United Statesâ post-World War II ascendance. He underestimated the Chinese, âgave undue attention to Latin Christendomâ and showed âscant concern for the sufferings of the victims of historical change.â

His subsequent books included the 1976 release âPlagues and People,â in which he was among the first to examine the impact of infectious disease in history, from ancient Eurasia to the 20th century. It helped launch a field of scholarship that includes Jared Diamond, Laurie Garrett and Richard Preston.

Other works included âThe Pursuit of Powerâ and a biography of Toynbee. In 2003, he collaborated with his son, J.R. McNeill, on âThe Human Web: A Birdâs Eye View of History.â His memoir, âThe Pursuit of Truth,â came out two years later.

He was born in Vancouver, Canada, in 1917. His father, John T. McNeill, was a theologian and historian; the younger McNeill would see his own scholarship as a secular version of his fatherâs calling. He studied at the University of Chicago, then got his PhD at Cornell University. His formal education was suspended during World War II when he served in the Army five years. But he continued to observe and absorb. He shared quarters with men of widely differing backgrounds.

âWhat better experience could a historian have than to find himself observing revolution and counterrevolution close-up?â he wrote in his memoir.

He married Elizabeth Darbishire. He joined the faculty of the University of Chicago and remained for 40 years.

He worked for years on what he knew would be his âbig book.â

âI typed the manuscript of âThe Rise of the Westâ on a portable Underwood noiseless typewriter that my parents had given me as a 21st birthday present,â he wrote in his memoir. âIt was accompanied by a verse my father composed inviting me to âwrite a book of lasting worth.â â

Leovy is a Times staff writer; Italie writes for the Associated Press.

UPDATES:

3:21 p.m.: This article was updated with additional quotes and details.

This article was originally published at 10:20 a.m.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.