âHe was the best one of usâ: Family mourns youngest son, who drowned in San Joaquin River

The funeral of Neng Thao lasted three days, around the clock, as is Hmong custom.

A bamboo pipe played to guide the 18-year-oldâs soul back through his life in Fresno and on to meet his ancestors. At one point, its song sounded like moving water.

The UC Berkeley-bound honor student was one of at least 17 people who have drowned during what may be the deadliest year on Central Californiaâs rivers. The waters â deceptive, cold, swift â come after at least five years of drought.

âWe were so happy to see the rain and snow. We had waited so long,â said Neng's oldest brother, Cha Thao, 36.

It was one of many things the Thao family was grateful for.

Earlier on the May day that Neng was pulled under by currents in the San Joaquin River, relatives had watched his brother Touyee receive a masterâs degree in plant science from Fresno State with top honors.

âWe were screaming like crazy. We were so excited. It was supposed to be one of the happiest days of my family,â said Cha, who was born in a refugee camp in Thailand.

The Hmong, mountain people, had helped the Americans during the Vietnam War. After Saigon fell, they were killed and hunted. The ritual poetry chanted at funerals tells their story, including how many drowned crossing the Mekong River while trying to escape.

Neng was the youngest of 10 children, born in America long after the war, talkative and optimistic.

All the siblings are close. When they were growing up, their father, Chong Vang, always told them, "The closer together, the stronger each one of you will be," folding his hand into a fist.

"Age, ego, distance, time, it doesn't matter. We support each other," Cha said. "But Neng, we paid extra attention. He was such a fun kid. He was the last, the baby, and whatever he said he was going to do, he accomplished. We all agreed he was the best one of us."

A senior at Edison High, Neng was class valedictorian and president of the Hmong club. He was involved in fighting slumlords and running campaigns to combat drunk driving. He was a leader on the city's youth council.

He said he would come back to Fresno after he graduated from Berkeley, eventually run for public office and make the city more fair and welcoming. Everyone in his family believed him.

Most victims were young

The drownings this year have happened in different circumstances: raging white water, mountain streams, seemingly placid rivers.

The thing they all have in common is the force of the flow at a time when people may have forgotten how to judge a river. If they ever knew.

Most victims have been younger than 25. For years, they saw only dry river beds and weak water.

The month before Nengâs death, Alondra Orozco and Shreya Singh, both 21, drowned in the Tule River to the south.

It was a cool, gray day, and the friends â students at Cal State Bakersfield, the first generation in their families to go to college â had no intention of swimming.

Singh had walked out on a rock to look at the water. But it was slick as ice. When she fell into the river, Orozco jumped in to try to rescue her.

Neither woman had a chance, Tulare County Sheriffâs Lt. Kevin Kemmerling said. The Tuleâs run is steep, its bottom granite. The raging water was frigid snowmelt.

Kemmerling said he's seen tragedies in his time working swift water rescue, but this was one of the worst.

"Both these girls were so sweet, good in school, good to their families and had their whole lives in front of them," he said.

The recovery of their bodies was harrowing. Two rescuers went into the rapids and had to be pulled in with their safety equipment. The Tule is now closed. Warning signs are posted.

The most deadly time on California rivers, according to experts, is usually Memorial Day weekend, when the snowmelt, high temperatures and crowds converge. This year, there were three deaths and 29 rescues in Tulare County over the holiday.

Typically, the rivers have calmed by the Fourth of July. But this year, with a record-breaking Sierra snowpack just beginning to melt, the water will be high, fast and freezing.

"Even if a river looks like its peaceful, there probably is an undercurrent," Kemmerling said. "I'm so grateful to have the rivers back, but right now they're dangerous."

Brothers overwhelmed by guilt

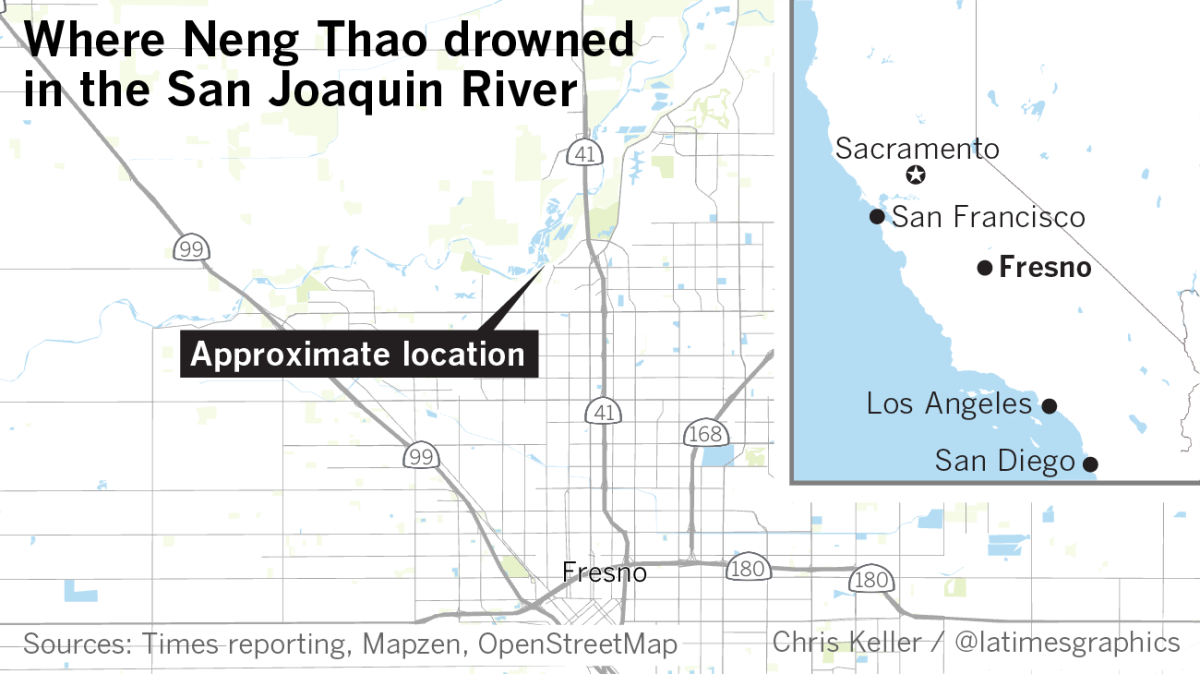

The spot on the San Joaquin River where Thao drowned looks placid.

An unmarked trail behind a shopping plaza leads to the popular swimming hole. Office buildings tower over one of the city's few public access points to the water. An effort to build parks and walkways has been delayed for years, largely blocked by politically connected people who live on the bluffs overlooking the river.

But this scruffy piece of land a bit north of the fancy houses is no man's land â or perhaps more accurately, everymanâs land.

In the early mornings, elderly Hmong men come to fish. People arrive in the afternoons with their children and their dogs. Many eat picnic dinners along the river, and there are late-night parties, judging by the beer cans visitors help pick up the next day.

Last year, this part of the river wasn't much more than mud. On the day Thao drowned it was full but, at least on the surface, meandering.

After Touyeeâs graduation ceremony, there was a big party in the family's backyard. It was a hot day. Three of the brothers, including Neng, and three cousins decided to cool off.

Neng, not much of a swimmer, was just going to dip in, according to his family.

They were wading when the current tugged and pushed at their legs. One of Neng's brothers slipped and another brother grabbed him. In that moment, the water pushed Neng away and he disappeared. The current that day was not full force. It has on some days since been 10 times stronger.

As the eldest son, Cha has the role to represent the family and hold them together.

His brothers, he said, are consumed with guilt over Nengâs death.

Touyee said that maybe if he had not won all those awards, maybe there would have been no party to leave. The brother who grabbed his younger sibling thinks he should have saved Neng too. The younger brother thinks it's his fault for slipping.

Cha's 4-year old daughter, whom Neng often babysat, wept for a week after the accident.

The funeral was held at the Fresno fairgrounds. Men chopped meat, women cooked rice, and the family followed the tradition of feeding all who came.

Inside where the bamboo pipe played were thousands of paper boats, folded by family and friends, meant to accompany Nengâs soul into the afterlife.

His cousin Michael Yang, 25, wore a mixture of Hmong and Western clothes to the funeral. He said he did it to honor Nengâs ability to combine traditional beliefs and modern life.

"For all his accomplishments and abilities, he still believed in the spirit, in the soul," Yang said. "He respected the ancestors. He was humble and wise, and I know he will guide his family."

Twitter: @DianaMarcum

ALSO

At Melvyn's, steak Diane is a staple and the dining staff spans the decades

Where grocery stores are sparse, one family farm nourishes a California town

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.