For volunteer interpreters at LAX, helping immigrants is personal: âSomebody here could be my motherâ

Sarah Fatemi knows what itâs like to be in the limbo of a foreign airport, hearing the chattering of voices that donât quite connect and trapped in the uncertainty about whatâs coming next.

She was 4 years old, returning from a family trip to Iran with her mother and younger sister, when the family stopped in Turkey â a common layover spot for return flights from Tehran. A misunderstanding over her motherâs immigration status led to a run-in with airport officials.

âNot one person spoke English. Not one person spoke Farsi. My baby sister was crying,â Fatemi, 24, said.

Four hours of questioning later, they were finally allowed to board a flight back to the U.S.

So after President Trump issued an executive order banning immigrants from certain countries from entering the U.S., Fatemi rushed to Los Angeles International Airport â armed not with protest signs or chants, but the power of language.

The college student answered the call of the interpreter.

âI am a person who travels back and forth from Iran. I know how hard and how long the flights are and how exhausting the flights can be,â she said.

The executive order blocks citizens from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen from coming to the U.S. for at least 90 days. It also imposes a ban for 120 days on refugees from any country entering the U.S. and bars refugees from Syria indefinitely. Trump has said the move will better protect the country against terrorist attacks.

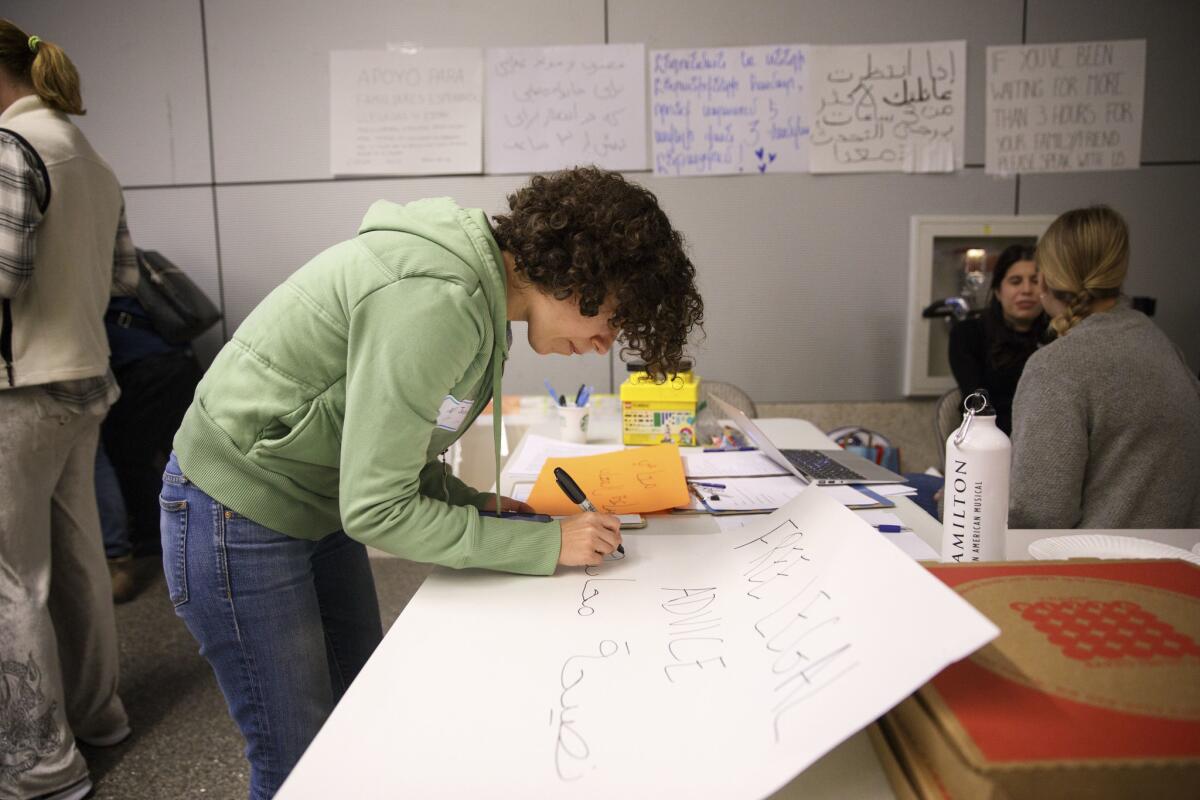

Protesters of all backgrounds descended on the airport while activists, advocacy groups and attorneys posted pleas for translators on social media. Most of the volunteers spoke Farsi and Arabic; some spoke Dari, Urdu and Armenian.

For all of them, answering the callfelt personal.

âMy cousin who is currently studying in America texted me that he was very distraught, worried that they want him to leave,â Fatemi said. âI was seeing a lot of posts from people like my friends who are from Iran.â

By Sunday, the volunteers were circulating through LAX in full force. Interpreters with name tags in at least two languages wandered the arrivals area and greeted passengers and families, asking whether they needed help. Fatemi walked around holding a red sign that read: âHave you been waiting for 3 or more hours for your family or friends? They may have been detained. Please speak to us.â

âGiven the current policies, there are more and more people who have this need,â Fatemi said of translating. âIâm not a lawyer and I really do think this is the way I can help.â

Fatemi also handed out chips and juice while helping travelers fill out intake forms handed out by attorneys.

âThey would fill out their personal information, [asked] were they treated respectfully, were they taken into a room were they forced to sign anything without being able to understand,â she said.

Fatemi, a student at Loyola Marymount University, said she often found herself helping Farsi speakers who also understood English, but felt more comfortable talking to someone in their first language. Others just needed emotional support. She recalled a distressed couple â a British-Iranian dual citizen and his Iranian wife who is waiting for her green card â who approached her.

âIf I have to go back to England, when can I see my wife again?â he asked Fatemi.

Fatemi said she has worked in the international office at school and taught English to international students, but had never done any formal language interpreting before.

Fatemi said she sees herself volunteering more in the future as demonstrations pop up and stories of detained immigrants continue.

On Monday, the arrivals area at the Tom Bradley International Terminal was filled with attorneys, but it was light on translators. Yassamin Maleknasr was one of a few Farsi speakers on hand trying to connect rattled family members with legal support.

Maleknasr, a 61-year-old filmmaker who emigrated from Iran decades ago, said she felt a deep personal connection to those who might be affected by Trumpâs order.

âSomebody here could be my mother, could be my aunt, a family member,â she said.

She huddled with a young Iranian woman as she cried near an encampment of attorneys. The woman was worried that her sister, who is a green card holder, might have been detained on a flight into LAX. The womanâs mother had also died in Iran recently, and she was afraid that if she flew back home for the funeral she would be denied reentry to the U.S.

âThere are a lot of good citizens â Iranian and American â and they are very scared now,â Maleknasr said.

Serving as an interpreter for those speaking Farsi, Dari and Arabic, Maleknasr held up a sign offering help to families of detainees as a steady stream of travelers funneled into the terminal. Some she directed to attorneys. Others simply needed a friendly face, she said.

âIâve been hugging a lot of people,â she said.

Haleh Golestani offered up her language skills because she didnât want to stand on the sidelines.

Golestaniâs family is Muslim, and while she wasnât personally affected by the ban, she wanted to help immigrant families.

âWe contribute to this country,â said Golestani, 30, who teaches at Cal Poly Pomona. âMy dad came here at 19 and he was able to make a good life for himself. How can you take that away from someone?â

Golestani said she worked with multiple Iranian families and acted as a liaison between attorneys and passengers to try to ease an increasingly stressful situation.

She said she would continue to translate as long as sheâs needed and plans to attend a prayer service at LAX on Friday.

Fatemi, the student, returned from a trip to Iran a few weeks ago. Her experience over the weekend reminded her of an exchange she had with her cousins there over lunch. Iranian ritual politeness, or taâarof, makes it impossible for a guest to pay when the bill arrives. The family fought over the check.

âThey said, âWhen we come to America, you can pay for us,ââ Fatemi recalled.

Now, she wonders whether sheâll have the chance to return the favor.

For more California news follow me on Twitter: @sarahparvini

Times staff writer James Queally contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.