Californiaâs truly loopy tax loophole

SACRAMENTO â You might think a tax law that rewards companies for killing California jobs and resurrecting them in another state would be dumped. Very quickly.

Especially if it also rewards them for selling off property here and rebuilding elsewhere.

Or, put another way, if the law provides a tax incentive not to hire or invest in California in the first place. Youâd repeal it. A no-brainer.

Makes no sense, except for the companies using the loophole while profiting from selling their products here in the nationâs largest consumer market.

You wouldnât even have voted to pass such a mind-boggling law.

But then you arenât a member of the California Legislature â especially a Republican who believes that any corporate tax loophole is good, any loophole closure is an evil tax increase.

Well, yes, closing the loophole would raise taxes for some out-of-state outfits â but only to the level already paid by California companies that hire and invest here heavily, and contribute substantially to our economy.

This is the kind of illogical policy that results when a two-thirds majority vote is required in the Legislature to exercise a routine constitutional power like raising taxes.

But letâs back up.

Before last year, corporate taxes were calculated on a formula that considered three factors: a companyâs sales, workforce and property in California. Many companies long had complained justifiably that this penalized job creation and facility building in California because expanding here would lead to higher taxes.

So three years ago, the Legislature moved to adopt a âsingle sales factor,â as many other big states had, including that conservative icon, Texas. Beginning in 2011, taxes would be based strictly on a companyâs sales in California. But lobbyists for the out-of-staters quickly pounced on the Capitol, complaining about higher taxes for their clients.

The inexplicable solution: Allow companies to choose whichever tax option best suited them: the old formula or the new.

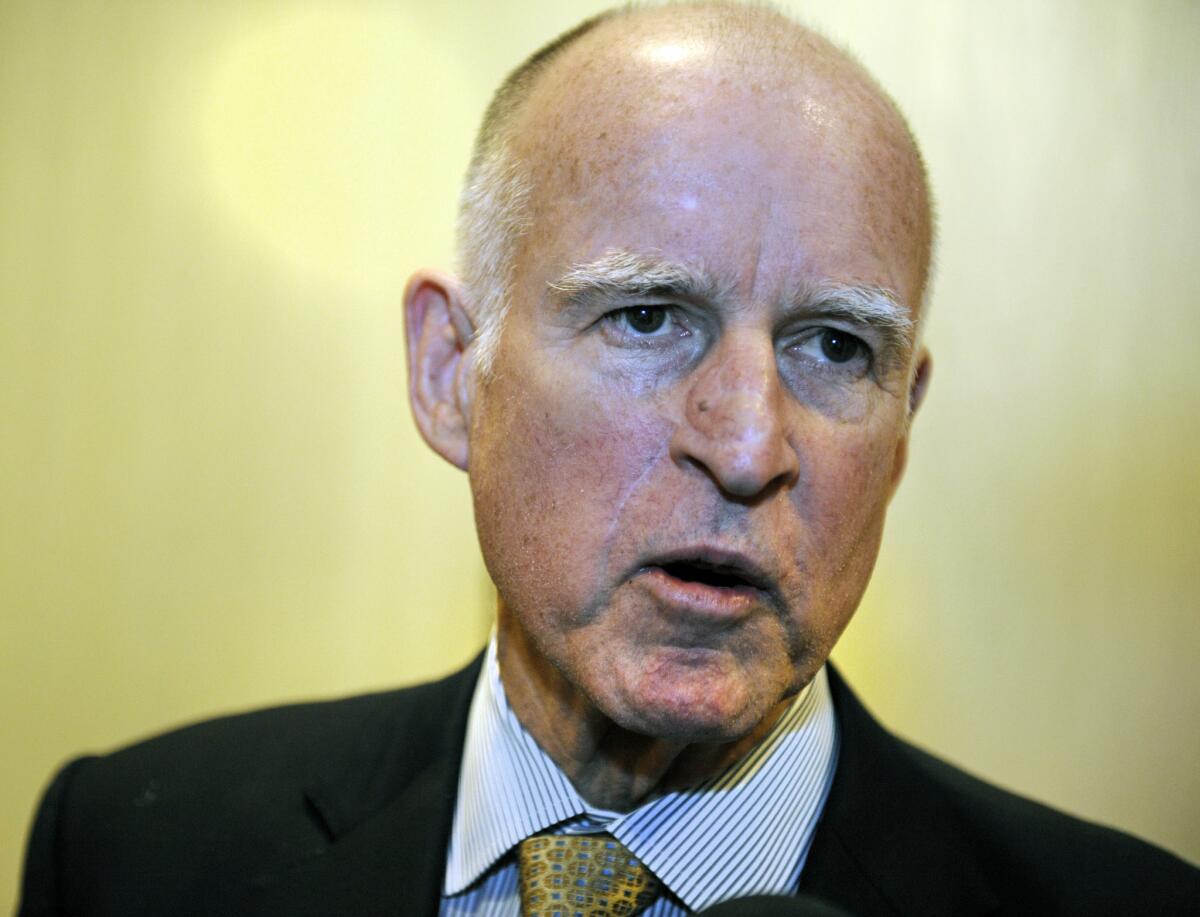

This corporate loophole was opened as a price for securing Republican votes in each house for income, sales and car tax increases â temporary hikes that Gov. Jerry Brown last year tried unsuccessfully to extend.

Those tax increases are long gone, but the corporate loophole remains, costing the state an estimated $1 billion annually.

âThis policy is an embarrassment to the State of California, if such a thing is possible,â says Lenny Goldberg, executive director of the liberal California Tax Reform Assn.

Sen. Kevin de Leon (D-Los Angeles) recalls: âIt passed at 2 a.m. with no one in the Legislature understanding what was taking place. We were dealing with very arcane, complex stuff. There was no hearing. No public testimony. And these are the consequences to our tax policy.â

De Leon failed last year in an attempt to close the loophole by making the âsingle sales factorâ mandatory.

Brown picked up the cause and negotiated a deal with two Assembly Republicans â Nathan Fletcher of San Diego and Cameron Smyth of Santa Clarita. The revenue increase would have funded tax breaks for small businesses, manufacturersâ equipment purchases and income-tax payers who donât itemize.

The two Republicans provided the necessary two-thirds vote for Assembly passage. But the measure died for lack of GOP support in the Senate.

It was a career-changing moment for Fletcher, an episode that exacerbated his disgust with party partisanship and ultimately led to his desertion from the GOP and re-registration as an independent.

Republican legislators confided to Fletcher that closing the loophole and helping small business âmay be the right thing to do, but we canât let Jerry Brown get a win,â the current San Diego mayoral candidate told me.

Enter San Francisco investor and philanthropist Thomas Steyer, founder of Farallon Capital Management.

âHow is it possible we could have this kind of tax loophole thatâs so bad for the state and for the people?â he asks rhetorically. âItâs just crazy. Itâs so nuts that I got exasperated.â

Steyer has all but collected enough signatures to qualify a âmandatory single salesâ initiative for the November ballot. Heâd use roughly 60% of the new revenue for clean energy retrofitting of buildings, creating up to 30,000 construction jobs. After five years, all that money would go instead into the state General Fund. The other 40% would go to K-12 schools and community colleges.

Steyer says the governor flashed him the green light to begin collecting signatures. But once it looked like the initiative would qualify for the ballot, Steyer says, Brown asked him to drop the measure. The governor was afraid it could distract from his own proposal to hike taxes.

Not after heâd already spent $2 million to collect the signatures, Steyer told Brown.

But Steyer promised Assembly Speaker John A. PĂŠrez (D-Los Angeles) that heâd step aside if PĂŠrez could coax the Legislature into finally closing the loophole. âIâve told the speaker that the minute his bill passes, weâre done,â Steyer says. âIâll stand down. Iâll save a lot of money.â

Steyer apparently is prepared to write a $20-million check for the initiative campaign.

PĂŠrez would use the $1-billion-revenue haul for middle-class scholarships at state universities. Students from families with incomes under $150,000 would have tuitions cut by two-thirds.

Rising tuitions âis one of our greatest challenges in the nation,â PĂŠrez says.

The speaker probably can push his bill out of the Assembly, but its prospects are dim in the Senate. Thereâs even some Democratic opposition.

Another Democratic bill, by Sen. Mark DeSaulnier of Concord, would use the loophole-closing money to care for returning war veterans. It already has been crunched in committee.

Only in polarized, impractical Sacramento would such a loophole be produced and preserved.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.