YouTube is a lifeline for transgender teens, twentysomethings

For those taking hormones, changing their names and feeling socially isolated, posting and watching videos lets them feel that theyâre not alone.

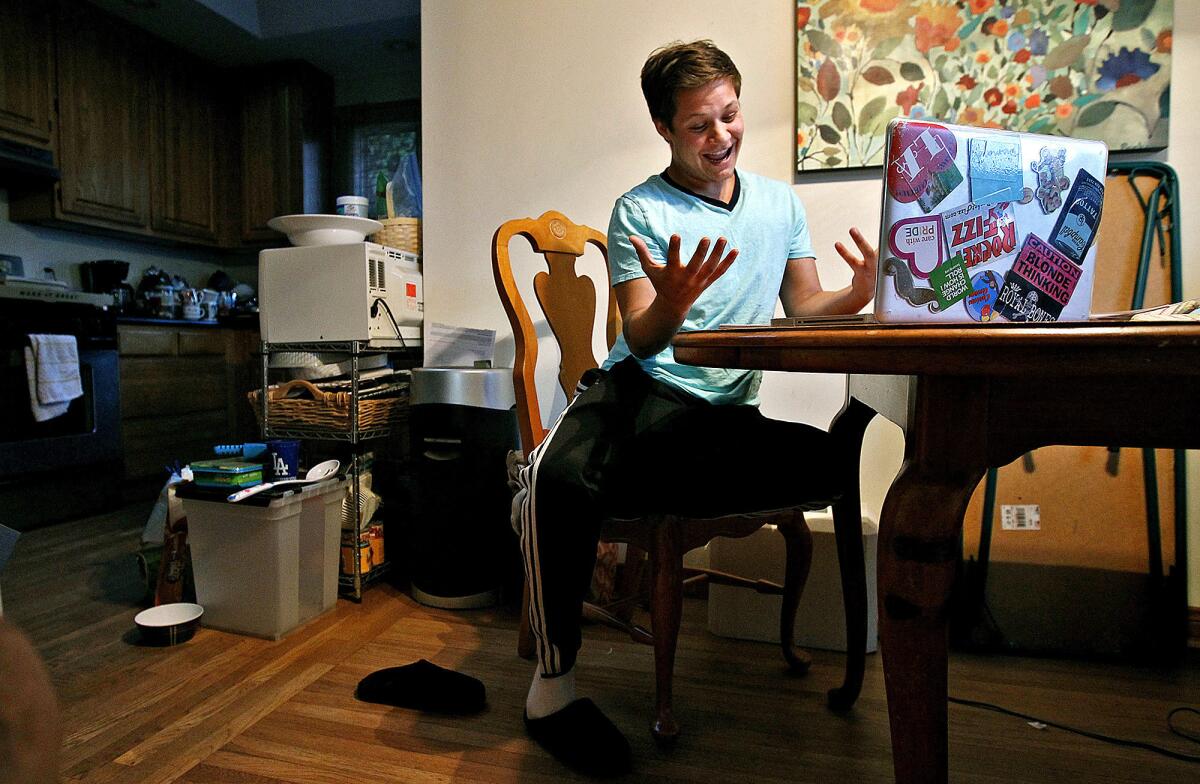

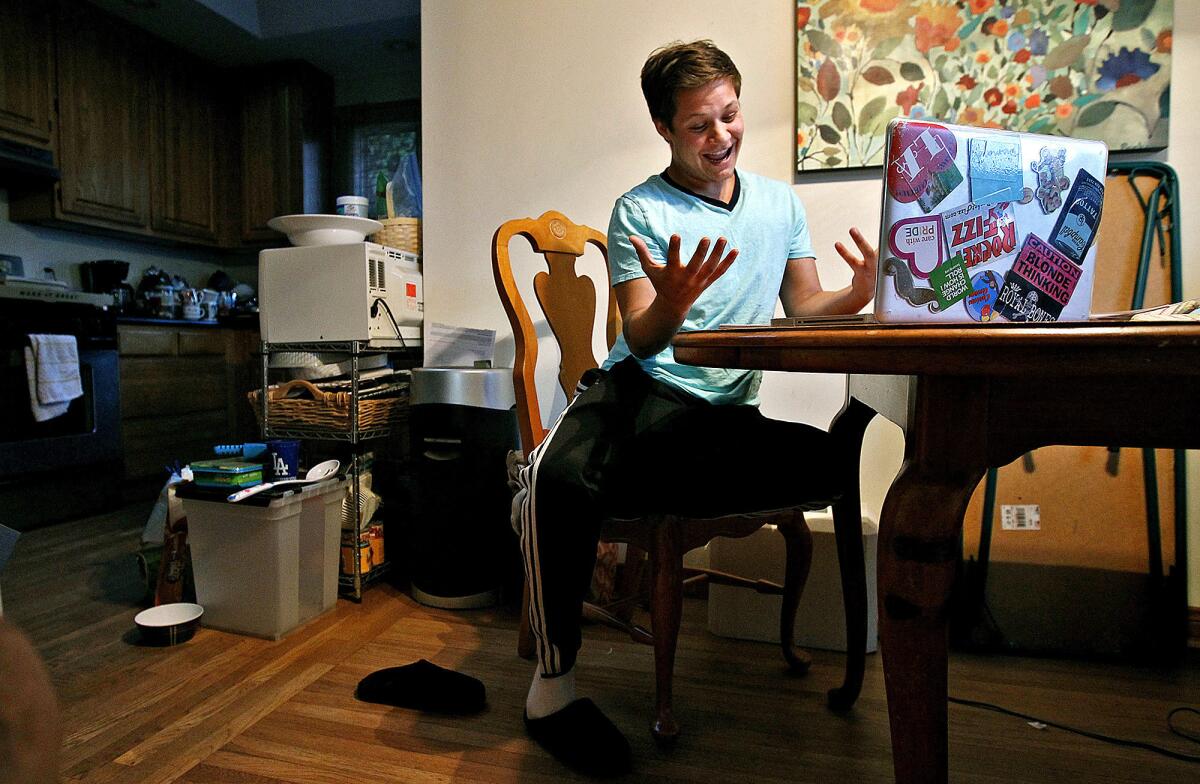

Behind the counter at Starbucks, Niko Walker wants to be seen as "just a guy." A guy who craves In-N-Out Burger and burns it off with P90X. A guy who looks like Jeremy Renner. A guy who dreams of making films.

On YouTube, he bares his chest to show his mastectomy scars, tracks his shifting hairline and shows how he injects testosterone. Hundreds of people watch. Questions pop up from strangers. At his Westchester home, facing the tiny camera on a laptop, the 21-year-old feels safe.

"I almost forget that I'm trans because I've had surgery," Walker tells his YouTube audience. But he keeps making the videos anyway, to support his transgender "brothers" still looking for help.

"I can't be quiet when three or four years ago, I was in the same position," he said one afternoon before he started to record.

As a high schooler, Walker stumbled across a video online and was transfixed as a faraway stranger started talking. Like Walker, the person on camera was born in a female body but identified as male.

Back then, classmates at Culver City High School knew Walker as a girl who liked other girls, a tomboy who goofily lip-synched to Justin Bieber. But Walker had never really felt like a lesbian, he said.

When the teen saw that video, "it was like, 'Oh my God. This person reminds me so much of myself.' "

Thousands of teens and twentysomethings who are transgender â identifying with a gender that is different than their sex at birth â have turned to YouTube as a kind of public diary. As they start taking hormones or using new names, many are documenting their journeys on video, baring their souls and revealing their changing faces to strangers online.

Their videos tell stories that were once routinely hidden: Transgender people were told to abandon their old lives and craft a new history after making their transition.

As recently as a decade ago, "you lost everything if people knew that you had transitioned," actress and activist Calpernia Addams said. "You eliminated dating opportunities. You exposed yourself to violence."

Three years ago, a national survey of more than 6,400 transgender and gender-nonconforming people found that 71% had tried to avoid discrimination by hiding their gender or gender transition. Sharing their stories remains risky: More than a third of people who were gender nonconforming or had a transgender identity before graduating from high school said they had been physically assaulted, the National Transgender Discrimination Survey found.

Violence and bias aren't their only worries: If "coming out" for gays and lesbians means being recognized for who they truly are, many transgender men and women feel that telling new people they are transgender does just the opposite, making people think of them as less than a "real" man or woman.

Naomi Ngoy, a 15-year-old in Utah, uploads makeup tips and videos about her transition. (Naomi Ngoy / YouTube) More photos

But sidestepping the past has become much harder for a generation that has had digital footprints since childhood. And many teens see little reason to do so, embracing their transition as an essential and even celebrated part of their identity.

"I'll always be trans," said Naomi Ngoy, a Utah 15-year-old who uploads makeup tips and videos about her transition on YouTube. Other video bloggers, or vloggers, have removed their videos once they are regularly recognized as their identified gender, but Naomi plans to keep hers online. "There's no point in trying to take them down in the future."

The videos are part of growing visibility for transgender people, but they are also a reflection of a younger generation used to broadcasting much more about their lives, whether trans or not.

Nearly half of Americans ages 18 to 29 have shared their own videos online, much more than among their elders, a recent Pew Research Center survey found. Another Pew survey found that among teens, nearly a quarter had put videos of themselves on Facebook or other social media.

At Survivors' Truths, a Los Angeles group that works with trans teens and others to tell their stories, "we ask youth, 'Do you have any concerns about putting this out there in the world?' " Executive Director Dove Pressnall said. Sometimes what might seem like spilling too much "is really generosity â a real desire to share what they've learned with that kid that's out there alone."

Although some teens and twentysomethings are eager to share their stories with the world, others have ventured into such a public space only to find community, said Tobias Raun, assistant professor of communication studies at Roskilde University in Denmark.

He calls the videos a kind of "private public," available to all but sought out by few.

A lot of people who watch my channel know me better than my family does.ââ Kat Blaque, an alias

"I'm not the kind of person who stands up and says, 'I'm trans,' " said one Long Beach vlogger who uses the alias Kat Blaque and didn't want her real name used for fear of losing work. "YouTube was my place to vent when I couldn't say anything to anyone."

During college, Kat gabbed regularly on YouTube about crushes, taking estrogen and retooling men's clothes to suit women, even as she fretted about classmates finding out she was transgender. In the years since, the 23-year-old has told some of her friends but still worries about employers finding out. Slurs in the YouTube comments needle her.

Despite such worries, Kat said she keeps vlogging because she wants to show women like her â particularly black trans women â that an ordinary life is possible. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of people have tuned in to see her recount her "worst night ever" in Hollywood, share her whimsical illustrations and banter on camera with her boyfriend.

And airing her troubles helps Kat too. Someone once sent her a box loaded with things to style her hair â blow dryers, flat irons and even a wig â after she vlogged about hair woes. It was the kind of thing a mother might do for a teenage girl. The kind of thing Kat said her own mother, uneasy with her femininity, never did.

"As bizarre as it sounds," she said, "a lot of people who watch my channel know me better than my family does."

Just a decade ago, when activist Jake Finney started his gender transition, there were only a few websites about the process, he said. Movies and television gave a grim picture of trans life â the rape and murder of Brandon Teena, the cancer that killed Robert Eads after doctors turned him away.

Now that trans men are talking about their own lives online, the 42-year-old said, teens have a vast library of stories: People who always knew they were trans. People who realized it later in life. People who are getting surgery. People who aren't. People with families, partners and jobs.

Asher Zickert says watching videos of other trans men reassured him that he wasn't alone. (Asher Ryen Zickert / YouTube) More photos

Today, teens can click through YouTube and see, "Oh â I actually can transition and lead a happy, healthy life," Finney said in Los Angeles.

Across the country in North Carolina, watching other trans men reassured Asher Zickert that he wasn't alone.

The 28-year-old made videos long before realizing he was transgender, discussing depression for an online audience. The old videos, still online, show a twentysomething with cascading reddish hair, dragging on cigarettes and offering advice about finding the right therapist.

When Zickert chose a new name, buzzed his hair and started taking testosterone, it made sense to him to keep making videos.

Sometimes seeing his own face on screen makes him grimace, but he presses record anyhow, talking through his frustrations with a virtual community: the lingering tenor of his voice, the steep cost of surgery, the occasional "ma'am" from others.

"I want to help the younger brothers out there that feel as lost as I did," Zickert said. "If there was no Internet, I probably wouldn't be where I'm at right now."

Follow Emily Alpert Reyes(@LATimesemily) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Teen's new media empire has fashion world on alert

The goal has become to make people feel...they're cool enough or smart enough.â

Family hopes genome test will help cure girl's mystery disease

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.