Deadly power of â94 quake was revealed at Northridge Meadows

A first responder realizes that the upper floors of the apartment complex had pancaked on top of the first. Inside, he calculates, 60 people, maybe. All trapped.

Alan Hemsath woke up to the earth cracking underneath him. Wood beams splintered above his bed, and the window shattered into small slivers.

He ran for the doorway, but the ground kept convulsing. As the apartment's walls crumpled, he fell face first onto his kitchen's concrete floor. His right hand was in a fist and pinned under his chest. A metal circuit breaker box collapsed onto his other arm. He opened his eyes, saw black and whispered the Lord's Prayer.

It was 4:31 a.m. on the third Monday of 1994, and he was trapped inside Apartment 110 of the Northridge Meadows apartment complex.

Half a mile away, the temblor tossed firefighter Mike Henry out of bed at Station 70. The two-story, brick firehouse jolted up and down and then rocked side to side. He tasted dust. Pieces of the ceiling had fallen into his boots, so he emptied them out and pulled them on.

He ran to his hook-and-ladder truck, waited for a few other guys to hop in and began to back out when an aftershock hit. Parts of the station collapsed.

Henry, who had turned 36 two days earlier, started south down Reseda Boulevard, along the route he was assigned to survey after earthquakes. He swerved around potholes and downed power lines.

"The whole valley was just pitch black," he said. "Dead, dead, dead black."

Northridge quake: Readers' memories | 1994 photos | Full coverage

Without street lights, he took intersections at a crawl â once slowing enough to see a dead dog. People ran into the street to flag him down and ask for help.

They'd be back, he promised, but they had to finish their survey first. There might be two people trapped here and 20 just up the road. He told them to help their neighbors and shut off the gas to help prevent fires.

As they continued down Reseda, people at every apartment asked the firefighters to stop. They couldn't. At Northridge Meadows, a beige, stucco complex with 163 units, a man ran up to the truck.

"There's a guy trapped under the building," he screamed. "And I'm talking to him."

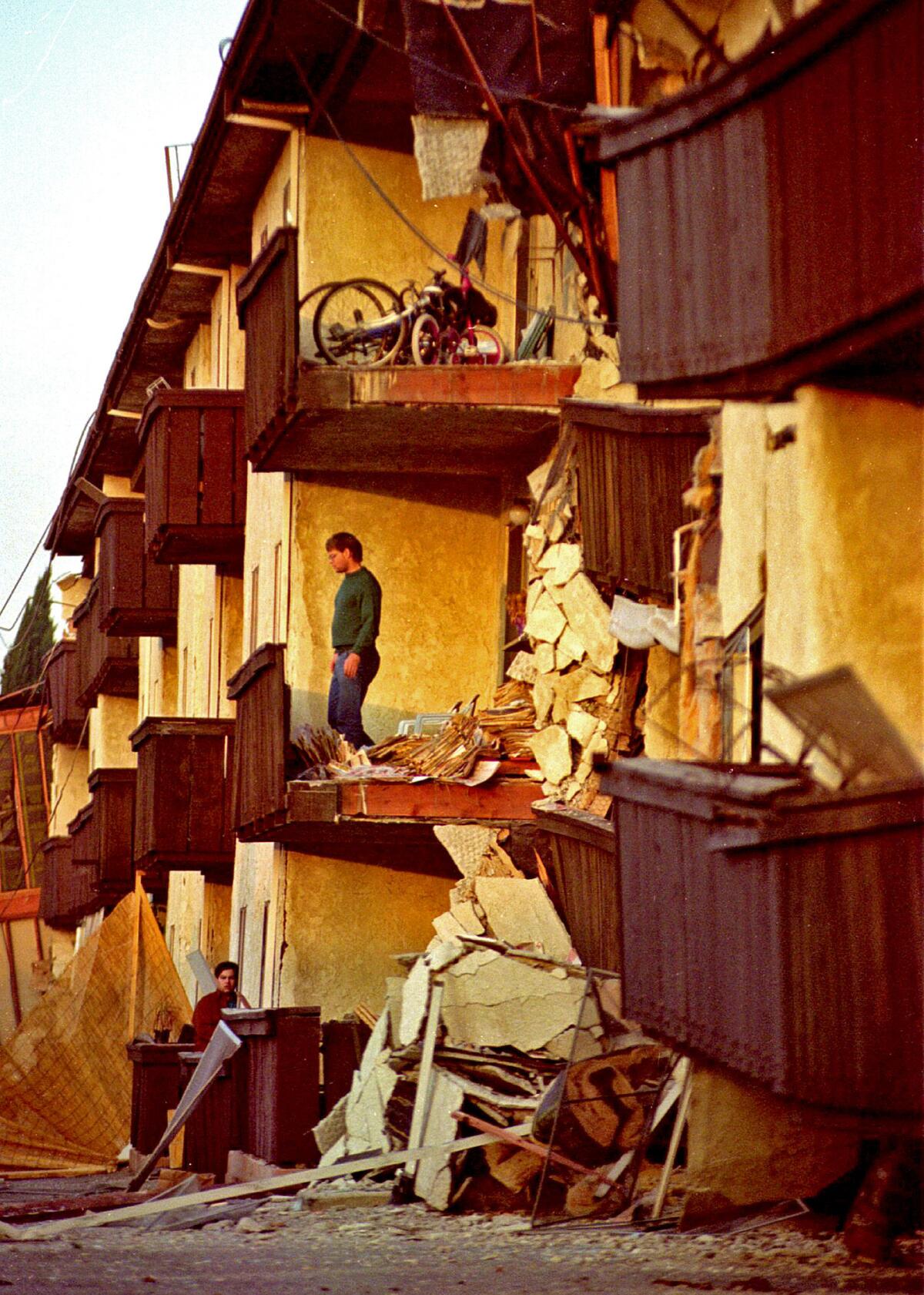

A man stares out from his wall-less home at the devastated Northridge Meadows apartments. (Los Angeles Times) More photos

The Northridge earthquake registered a magnitude 6.7 and stole about 60 lives. Tens of thousands of buildings were abandoned, razed and rebuilt. A mended Santa Monica Freeway reopened. Twenty years passed.

Quake preparedness: Making your home safe | New seismic safety concerns

You can't see most of what Jan. 17, 1994, did to L.A. anymore. Now, the memories are tucked away.

They're in a stack of tattered Manila folders at Northridge United Methodist Church, where survivors gathered that morning.

They're in the minds of the rescued and the rescuers.

The last man pulled alive from Northridge Meadows, who has reinforced his current home with shear walls and extra plywood.

The New York transplant, who stopped by Station 70 with three-quart jars of homemade marinara sauce every couple of months to say thank you.

The firefighter, who called home that morning and feared for the worst when nobody answered.

The 14-year-old boy who wanted to be a priest and his father, trapped in the bathroom where he'd been brushing his teeth before work.

The man at Northridge Meadows sounded different from the people at other apartments, Henry thought. His plea seemed more desperate, more detailed. But the firefighters continued on, toward a glow in the distance.

Henry pulled up in front of the house fire. If they couldn't stop it, he thought, they might lose an entire block. He sprinted to a hydrant, but it was dry. He tried another one. The quake had taken out the whole hydrant grid. Flames raged and a couple of firefighters stayed behind.

A doll lies amid the rubble in an area of Northridge Meadows where several bodies were found after the quake. (Richard Derk / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Henry continued to the Northridge mall, where a parking garage had collapsed onto a sweeper truck. A man was inside, so they radioed in the call and headed to a condominium fire. The firefighters there needed help, but Henry and his team couldn't stay. They had promised to retrace their route along Reseda.

This time, Henry said, the people rushing toward the truck sounded relieved. Everyone was accounted for at the apartments â until they got to Northridge Meadows.

It had been about 45 minutes since they first drove by, and the desperation had deepened. Henry parked the truck and hopped out. He approached a man who was sledging the building's base with a hammer and saying that his neighbor was trapped below.

Impossible, Henry thought. How could someone be under the first floor?

He stepped away from the building, pointed his flashlight at the roofline.

"My God!" he thought.

He'd assumed it was a two-story complex on the initial drive-through, but now he realized that some of the second and third floors had actually pancaked on top of the first. Numbers began to race through his mind. Fifteen to 20 apartments per floor, he guessed. At least two people per unit. Forty. Fifty. Sixty people, maybe. All trapped.

Cap, this building's collapsed. I have a guy over here who says he's talking to somebody. I'm going to start there.ââ Mike Henry

Henry broke the news to his boss and told him his plan.

"Cap, this building's collapsed," he said. "I have a guy over here who says he's talking to somebody. I'm going to start there."

He hopped through the second-floor window, which had fallen to about five feet above ground. The quake had heaved Cal State Northridge student Robert Dorsey chest-down onto a metal, two-drawer filing cabinet. The ceiling of his first-floor apartment collapsed onto his back and he was pinned down. Henry listened for Dorsey's voice through a slab of concrete and picked up an ax.

When he finally broke through, the hole was too far from Dorsey, so he made another. A fellow firefighter used a crowbar to pry away the debris wrapped around Dorsey.

The sun was cresting the horizon now, offering a portrait of devastation worse than they imagined. But as the rescuers carried Dorsey out on a closet door, they heard claps and cheers.

Henry paused for a second. Exhilarated, exhausted. He couldn't stop thinking about his home in Simi Valley. About his wife, 3-year-old son, baby girl. If it's this bad here, he thought, what if that's the epicenter? Was somebody digging them out of rubble?

His captain rushed over and assigned him another rescue: a young boy.

Hyun Sook Lee, a nurse who spoke mainly Korean, used hand gestures to try to explain that her husband and eldest son were trapped. It was hard to communicate, Henry said, so they guessed at a spot and sawed open a hole. And then another and another. Finally, they found 14-year-old Howard. He had suffocated in bed.

The discovery of Howard and, later, his father shattered Henry. He needed a break.

LAPD Reserve Search & Rescue worker Don Stein, right, helps remove Steve Langdon from the collapsed Northridge Meadows apartments. (Los Angeles Times) More photos

Several hours had passed now and backup was starting to arrive, so Henry searched for a pay phone. He found one and dialed home. No one answered, so he headed back to Northridge Meadows. He collapsed onto a patch of grass and ate an In-N-Out burger that someone had brought. Inside, the digging continued, but it was mostly turning up bodies.

Then a couple of guys from a volunteer community emergency response team rushed his way. They had found a guy trapped and said he was still talking. The prospect brought a jolt of energy, and he headed back to the rubble.

A smile spreads across Henry's face â still boyish but weathered by years of sun â when he describes rescuing Jerry Prezioso.

The 67-year-old hadn't had time to get out of bed, and a piece of wood framing from the wall with nails sticking out of it had collapsed onto his stomach. They couldn't pull it off, Henry said, because it would have torn open Prezioso's skin. Instead, he cut around it with a chain saw and hoisted the New York-transplant-turned-gregarious-bartender out of the hole.

Every month or so after that morning, Prezioso stopped by Station 70. His thank-yous always came in the form of homemade marinara sauce. They stayed in touch, and when Prezioso went into the hospital years later, Henry and his family â who weren't hurt in the earthquake â visited him a couple of times a week.

He died a couple of months after the quake's 10th anniversary.

Alan Hemsath, left, Jerry Prezioso and Steve Langdon were the last survivors removed from Northridge Meadows. Langdon and Prezioso shared Apartment 106, which used to be on the slab on which they sit. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) More photos

A fresh batch of firefighters finally showed up, and Henry headed back to the station. The search continued into the night, but after Prezioso and his roommate, only one tenant was pulled out alive.

Hemsath, the man in Apartment 110, said a firefighter had found him and dug a hole above him. But getting him out was tricky and took a few hours. They had maneuvered a wood beam off his leg but couldn't lift the electrical box pinning down his left arm. They considered amputation, but eventually decided to wedge an air bag under the box and hoist it up just enough to wiggle him free.

"I was the last guy out of there," Hemsath, now 57, said as he traced his index finger along a scar the length of his left forearm. The general contractor spent a week in an intensive care unit and then several more in the hospital. After his release, he returned to Northridge Meadows and salvaged a mug he had gotten at an Elvis Costello concert. He keeps it on a shelf of his home, where his bedroom is on the second floor.

Things aren't like they once were, he said, where almost everything reminded him of the earthquake that had killed 16 of his neighbors. Now, 20 years later, there are still reminders. But you have to dig for them.

Jiyoun Sim checks a list of Northridge Meadows survivors at a church. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) More photos

At Northridge United Methodist Church, employee Joan Coston sometimes pulls the folders out of a cabinet before an anniversary.

Its contents tell slivers of the story that unfolded in the weeks after the earthquake. There's a yellowing newspaper clipping of National Guardsmen patrolling for looters and an eight-page, handwritten list of survivors who checked in at the church.

There's a Polaroid of an 84-year-old woman with a description of her beige, two-door Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme with two keys duct-taped to it. The street where it was parked was blocked off, and she wanted someone from the church to move it when it reopened. She never came back for the keys.

"I can't believe it's been that long," Coston said.

She pulled a stack of papers out of a folder, and a small card fell on her lap. She smiled sadly.

It has a red flower and a verse from Psalms in Korean on it. In blue pen, on the back, someone wrote: "1-17-94 James & Howard Lee."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.