Nelson Mandelaâs unforgettable face, spirit captivate film world

The year is 1992. Nelson Mandela, two years beyond his release from 27 years of political imprisonment and two years before he will be elected president of South Africa, stands before a classroom of Soweto children.

A rare moment is being captured by camera and crew: Mandela as actor, rather than activist. Cast in the role of teacher, handed words to speak that are not his own.

The only backdrop is a blackboard. Erased, it is a clean slate, but evidence of lessons past cling in the chalk powder. A subtle statement of its own to match the man whose passing Thursday â as well as his life â leaves traces that will cling forever.

The scene comes late in Spike Leeâs âMalcolm X,â the filmmakerâs biography of a very different political rebel. The lines Mandela has been given are among Brother Malcolmâs most famous, drawn from a 1964 speech at the founding rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity. And yet, as Mandela would do so many times over the course of his 95 years, the words, the moment, carry his imprint.

FULL COVERAGE: Nelson Mandela (1918-2013)

âWe declare our right,â he begins, setting those indelible words to his own rhythms, his English accented by his South African heritage, âto be a human being, to be given the rights of a human being, to be respected as a human being in this society on this earth in this day.â

Then that insistent voice goes silent, refusing to raise Malcolm Xâs final battle cry â âby any means necessary.â Lee instead cuts to archival footage of Malcolm X saying the line familiar to so many.

Itâs fitting that Mandelaâs Hollywood moment would reflect the man and the uncompromising way he chose to wage war against apartheid, the great enemy he would wrestle to its knees.

Lee was far from the only director drawn to Mandela. The face, unforgettable, as well as the spirit of the man captivated Hollywood. His life was a series of dramatic arcs so compelling that fiction writers would not have dared create so many trials and triumphs for one man. Its reality would lead filmmakers to try.

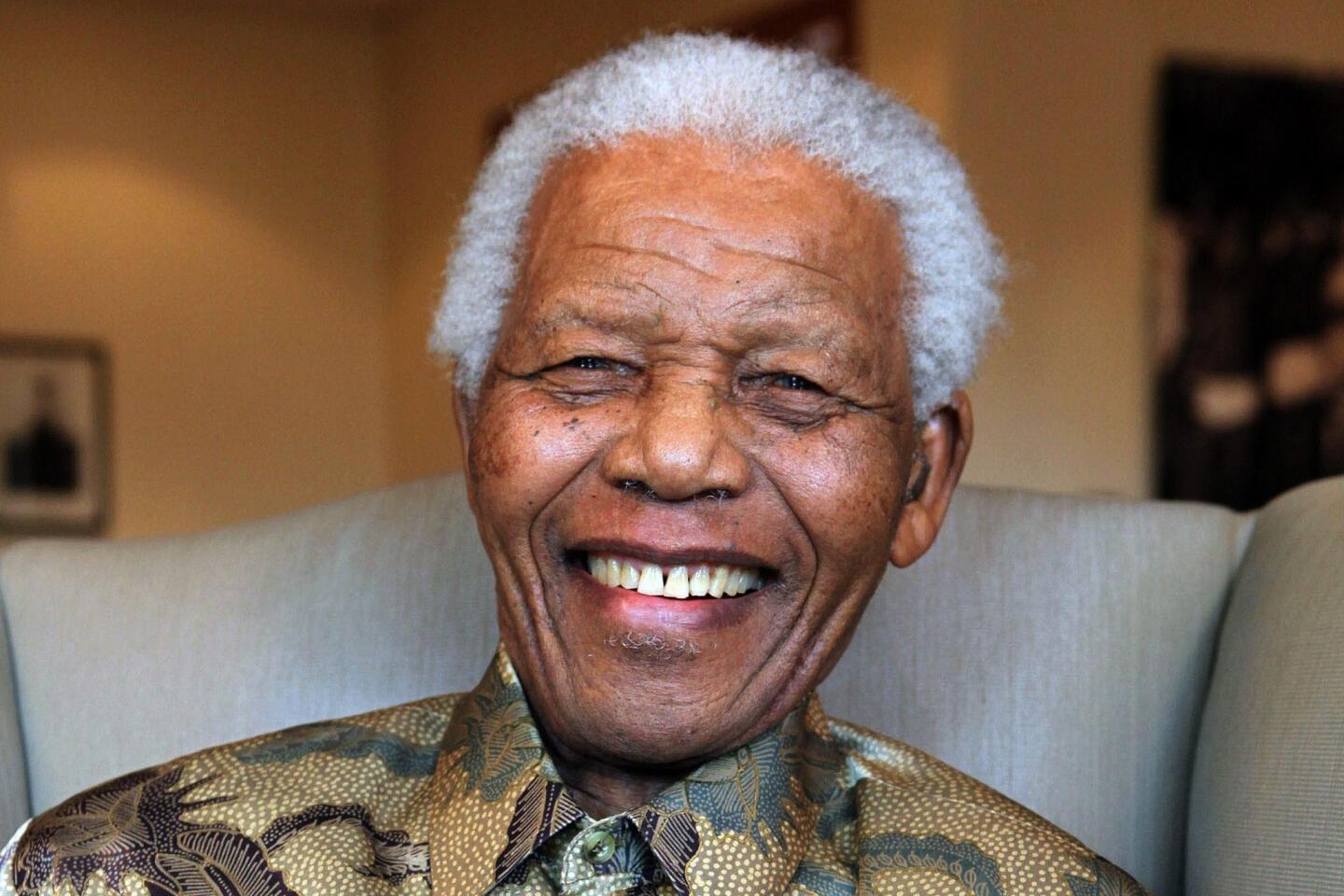

Rarely does the exterior mirror so fully the interior as it did in the South African leader.

It was a face marked by his struggles, the crevasses worn deep by those long years as a political prisoner, most of it on Robben Island. The eyes, filled with emotion, were scarred by the sunâs constant glare on the prisonâs limestone quarry where he broke rocks and contemplated how to rebuild a nation.

PHOTOS: Actors whoâve portrayed Nelson Mandela on screen

In time joy, empathy and woe would overtake the look of anger, determination and frustration that can be seen in news footage of the young rising voice of the African National Congress. For Mandelaâs was ultimately the face of forgiveness and reconciliation. Those chiseled cheeks made less imposing by an irrepressible smile, that arrow-straight bearing never carrying arrogance or self-righteousness in the gait.

Indeed, it was the fusion of elements â magnetic smile, inclusive nature, unyielding integrity â and an ability to telegraph all of it through the lens, that made Mandela such a compelling figure on-screen.

Filmmakers would try to tap into that aura in any number of ways. Each chapter of his life carried its own distinct journey and movies would busy themselves taking on specific periods â the early years, the prison years, the presidential years, the post-political years.

More than a decade after Lee, Clint Eastwood would pick a particularly rich episode in Mandelaâs life for examination in the 2009 film âInvictus.â It is the story of the newly elected leaderâs unconventional bid to help heal South Africaâs racial divides with the Springboks rugby team and its run for the World Cup in 1995. The film starred Morgan Freeman as Mandela and Matt Damon as the team captain. More of a heartfelt appreciation than an artistic achievement, the movie underscored the challenge of re-creating Mandelaâs unique qualities.

Though Freeman had the lean frame and the infectious smile, the pacing of Mandelaâs clipped speech eluded him. Mandela was so precise, so deliberate, so nuanced when addressing anyone about anything that it is almost impossible for any actor to replicate him without seeming stilted.

OBITUARY: Nelson Mandela, anti-apartheid icon, dies

Dennis Haysbert struggled with this in 2007âs âThe Color of Freedomâ (also known as âGoodbye Bafanaâ), based on the memoir of Mandelaâs chief prison guard. Both movies are ultimately about Mandelaâs transformative influence on others and are best, Eastwoodâs in particular, as they hone in on Mandelaâs expansive humanist side.

At the time of the âInvictusâ events, Mandela was being tested at every turn. The Springboks became a flash point. To South Africaâs racial and ethnic underclasses, the team remained a symbol of apartheidâs repression. To the countryâs whites, it was a piece of the national identity.

As much as anyone in history, Mandela understood the power of imagery to persuade, and of sports to unite. In the World Cup and the Springboks he had both. The team did its part by winning.

With Eastwoodâs ability for distilling complicated situations, the film becomes a tangible expression of one of Mandelaâs guiding tenets â to be more compassionate, more forgiving, more inclusive than those who came before him.

Better at capturing Mandelaâs voice, and his intellect, was Joe Sargentâs 1997 TV movie âMandela and De Klerk,â starring Sidney Poitier and Michael Caine. In Poitierâs performance you sense the steel it took to survive; there is more fire in this Mandela than most, and the soul of the peacemaker who would share the Nobel Prize with De Klerk in 1993.

But for the most part, directors wanted Mandela for Mandela. He is prolifically represented in the documentary world via news footage and through the impressions and insights of others. Though there were any number of films on his early life, prison years and release, it is his post-prison voice â one of inspiration and reason â that you hear most often.

PHOTOS: Nelson Mandela through the years

Mandela was a man of the people, thronged wherever he went. Yet he had a gift for making those public moments intimate. There is an accessibility â emotionally, intellectually, literally â in clip after clip. Whether he is grasping the outstretched hand of a stranger on the street, speaking to thousands, conversing with world leaders, bending to talk to children, there is a singular focus that is riveting.

As you watch the footage culled by documentarians through the years, there are significant changes too. The fist that was so often raised in defiance during the early days of the apartheid resistance comes to rest more often against his forehead in his later years. It is a more contemplative look, almost prayerful, and it speaks to the reconciliation that he made his lifeâs work. The smile deepens, the eyes soften, the hair goes completely white.

The dignity is carried with even more grace in his final days, the cane he gripped a reminder that at heart, he was human.

Perhaps it is appropriate that the most creatively ambitious film about Mandelaâs life arrived in theaters just days before his death. The timing certainly increased the expectations for âMandela: Long Walk to Freedom.â The film, directed by Justin Chadwick, a Brit who seems to be making stories of Africa his mĂŠtier, stars Idris Elba in the title role and Naomie Harris as his most controversial wife, Winnie.

It is written by the well-seasoned William Nicholson, who has Oscar nominations for âGladiatorâ and âShadowlands.â And there is talk that Elbaâs performance could be an Oscar contender. Though the actor comes closer than most to capturing Mandelaâs spirit on screen, once again it proves impossible to outshine the man. History is etched in that face, a force and a legacy in its creases that even the coming years cannot dim.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.