When Hollywood unexpectedly expressed its outrage and social consciousness

â12 Angry Menâ

âThe Angry Hills.â

âAnger Management.â

âThe Last Angry Man.â

âAngry Birds.â

Throughout its history, the only reliable place anger can be found in Hollywood films has been in their titles. With one unexpected exception.

On one level, this absence is perfectly understandable. Film studios are in the entertainment business, after all, and experiencing anger is not a central reason why audiences seek out movies in the first place.

And if they do gravitate toward fury, Hollywood films tend to traffic in personal dissatisfaction, not the kind of anger toward society and its intrinsic unfairness that has been a key factor in the current presidential race.

There have been, of course, random outliers, films where rage against the machine is a central element. Most prominent here would have to be 1976âs âNetwork,â directed by Sidney Lumet and written by Paddy Chayefsky.

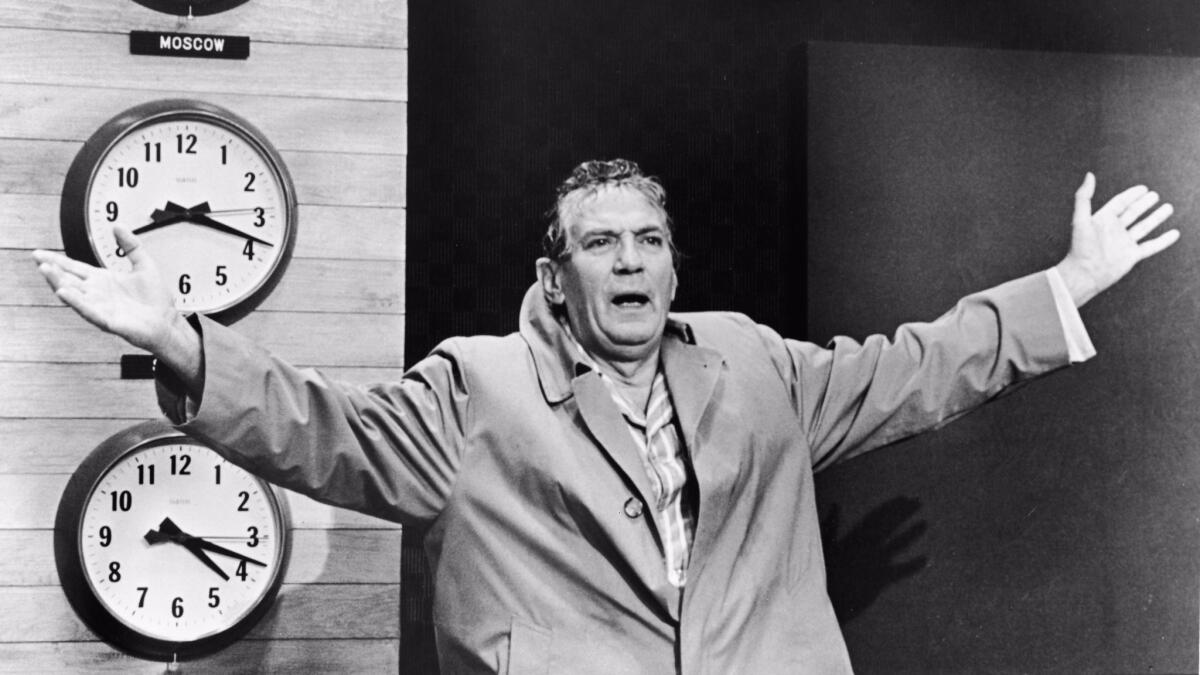

Chayefskyâs brilliant, corrosive âIâm as mad as hell, and Iâm not going to take it anymoreâ monologue for TV newscaster Howard Beale won a posthumous lead actor Oscar for star Peter Finch (and an Oscar for the writer as well.) Watch the clip on YouTube and experience a raw anger that has not lost its bite 40 years later.

There was a period, however, when, unlikely as it seems, one Hollywood studio made it its business to take on the ills of society, to be as disenchanted with the way things were as any supporter of Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump.

That studio would be Warner Bros., and the period is one thatâs come to be known, after the fact, as pre-code Hollywood. It encompassed the period roughly between 1930, when sound film was just finding its footing, and 1934, when the Production Code, an industry-wide censorship apparatus, began being enforced.

If film buffs today think of pre-code films at all, they think of them in terms of their bold and risquĂŠ sexual content, the way they were, as Thomas Doherty writes in his authoritative âPre-Code Hollywood,â âmore unbridled, salacious, subversive and just plain bizarre than what came afterwards.â

But there was another side of pre-code â the angry, socially conscious side so furious at what the Great Depression was doing to America that it made room for Al Dubin and Harry Warrenâs lament for the downtrodden, âRemember My Forgotten Man,â in the otherwise giddy Busby Berkeley-Mervyn LeRoy musical âGold Diggers of 1933.â

A combination of factors led to these films, including the severity of the national crisis, the anything-goes youth of the sound film industry and the personalities of the Warner brothers themselves. As Neal Gabler writes of the Warner studio output in âAn Empire of Their Own,â âif their films lacked refinement and glamour, they did have a conscience â deliberately so.â

For those interested in this side of pre-code, three films come immediately to mind: 1932âs âI Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gangâ and two 1933 features, âWild Boys of the Roadâ and âHeroes for Sale.â

MORE: Anger is just below the surface in many new movies Âť

Directed by LeRoy, written by Howard J. Green and Brown Holmes under the careful eye of Warner Bros. head of production Darryl Zanuck, âChain Gangâ was adapted from the true story of Robert E. Burns, who was literally in hiding when his book âI Am a Fugitive From the Georgia Chain Gang!â was published.

The film tells the story of a returning World War I veteran who, despite his best intention, finds himself unemployed and penniless, a classic âforgotten manâ right out of the song, reduced to sleeping in 15-cent-a-night flop houses.

Involved unintentionally in a robbery in an unnamed state, the man is shocked to end up on a savage chain gang, a pitiless, dehumanizing institution where you can be beaten for wiping the sweat off your face without asking permission.

A furious film that openly mocks the notions of establishment justice and honor, âChain Gangâ is most remembered for its chilling, almost terrifying ending, one of the most famous in Hollywood history, that underlines the bleak and fatalistic nature of its view of how society is rigged against honest folk who donât control the levers of power.

Both âWild Boys of the Roadâ and âHeroes for Saleâ were directed by the vigorous William A. Wellman, whose feeling for those society cast off was visible as early as his 1928 silent âBeggars of Lifeâ starring Louise Brooks.

âWild Boys of the Road,â advertised as dealing with âthe abandoned generation,â stars Frankie Darro and Dorothy Coonan as members of a small army of young people forced to become vagabonds and ride the rails because of impoverished parents. Basically good kids, they are overwhelmed by the miasma of poverty and end up fighting anarchic pitched battles with unfeeling police. âAinât you afraid?â someone asks a young lady riding the rails alone. âWouldnât do me any good if I was,â is her edgy reply.

âHeroes for Saleâ is if anything tougher and angrier. It stars sad-eyed Richard Barthelmess, a major silent film star (both âBroken Blossomsâ and âWay Down Eastâ for D.W. Griffith) whose sound career did not match his early glory, which adds a further touch of poignancy to the proceedings.

Bathelmess plays another WWI veteran, who gets a morphine addiction instead of the medals he deserves and then endures bread lines, labor unrest and the scrutiny of the sour-faced Red Squad. More even than its pre-code co-conspirators, âHeroes for Saleâ actively explores the idea that Depression America was close to total collapse. Itâs a film thatâs angry at the direction this country was taking in a way weâve forgotten Hollywood can be.

MORE:

On TV, rage has become the new romance

Anger is an energy for a new wave of women in pop culture

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.