Review: With âDouble Visionâ at LACMA, 3-D art strives to find a new dimension

Height, width, depth. Every kind of object in the world â except one â can claim all three measurements.

Often, art doesnât measure up. Physical depth is missing from the likeness found in a painting, drawing, photograph or print. The flatness of the surface plane establishes a formidable if obvious obstacle. For centuries, artists have grappled with the impediment in myriad ways.

The exhibition â3D: Double Vision,â currently at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, deftly traces one specific history of the pesky conundrum, beginning in the 1830s. That was the decade of two important, nearly simultaneous technical developments.

The camera was invented in 1839. And, barely a year before, so was the stereoscope, which creates an illusion of three dimensions.

A stereoscope is a device that juxtaposes two similar or identical images. Sometimes using lenses or mirrors and sometimes not, the device forces each of a viewerâs eyes to see only one of the paired pictures. The brain, discomfited by the related but dissonant signals being sent through the optic nerve, handily knits the discordant ocular inputs together.

Voila! An appearance of real objects occupying actual space forms in the mindâs eye. Order is resolved from visual chaos.

Britt Salvesen, LACMA curator of photography, prints and drawings, has assembled a captivating array of material produced since the mid-19th century by scientists, inventors, designers, engineers and, of course, artists â all keen on experimenting with or expanding 3-D visual effects. Sheâs organized the show into five coherent sections.

First is an introduction to the mechanics of binocular vision. Then come popular commercial applications dating to the Victorian era and to postwar America. (Remember the 1952 Robert Stack movie âBwana Devil,â one of Hollywoodâs first 3-D movies?) Next is the art and technology movement of the 1960s, which coincided with the perceptual expansions of the psychedelic era. Finally, a sampling of more recent work accompanies the emergence of virtual reality in the digital age.

Along the way, in addition to scientific displays and commercial applications, there are photographs, videos, paintings, drawings and mixed-media sculptures by diverse artists. They range far and wide.

Lygia Clark altered swim goggles to discombobulate bodily perceptions. Painter Oskar Fischinger made a pair of geometric abstractions that, when stared at long enough, send triangles and disks floating in space. Man Ray affixed a lenticular photograph of a human eye to the arm of a ticking metronome, causing it perpetually to blink.

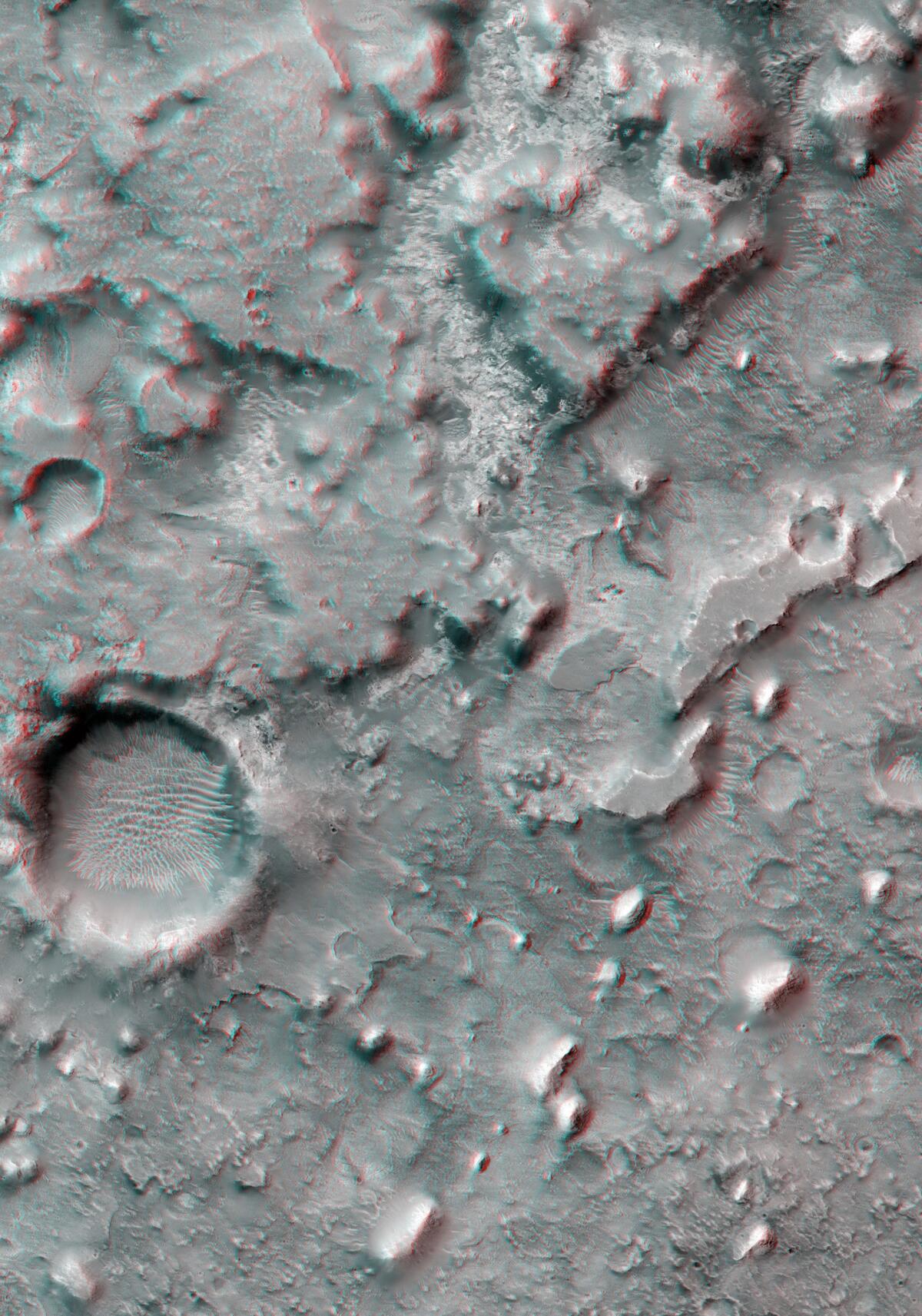

Simone Forti performed a holographic dance across a curved sheet of clear plexiglass; as you walk by, she pops up and then takes a graceful tumble. Thomas Ruff made monumental photographic prints of the surface of Mars â more than 8 feet tall â which burst into three dimensions when red and blue anaglyph glasses are donned; wittily, conspiratorial visions of a faked moon landing fabricated in Area 51 come to mind.

Experimental filmmaker Ken Jacobs is among the few artists to use 3-D technology extensively. Here, putting an illusion of movement to haunting poetic effect, he transforms an 1895 stereograph of a prosperous Gilded Age crowd into a relentlessly âSurging Sea of Humanity.â The nearly 11-minute video, which wavers between hypnotic and nauseating, was made a dozen years ago but feels up to the minute. Civilization swells and drowns in thrilling and self-destructive waves.

Still, for all the stereoscopes, lenticular lenses and holographs, few sustained bodies of significant work will be found. Artistically, the show seems thin. Except in a few cases, such as Jacobsâ, if an artist chooses to employ 3-D technology, most often it appears to be a one-off, or else limited to a specific project.

There are fascinating sights to see, but â3D: Double Visionâ is mostly a gizmo show. Stations throughout the exhibition feature hands-on activities, including View-Master toys, popular in the 1950s and 1960s.

3-D imagery has popular appeal, but interest in it waxes and wanes. âMoviegoers are putting down the colored glasses,â Variety reported last spring in a story about a sharp 18% drop in revenues for 3-D movies. Lines at the local multiplex have dwindled since their 2010 peak, when âAvatarâ was packing them in.

The short shelf life of novelty surely has something to do with it. (Kids between 12 and 17 are the biggest 3-D fans, Variety noted.) But, for art, so do other pressures: Commercial applications of 3-D technology dominated the first hundred years, with the big uptick in artistsâ interest holding off until the 1960s.

Was the â60s boost a rebellion against formalist tyranny? Formalism claimed illusion was the enemy of painting, while the two-dimensional surface of a canvas got championed as the mediumâs most distinctive â and therefore most honorable â quality. The tricks of illusionism were scorned as the stuff of popular art, a deception with immoral overtones.

Tell an artist she absolutely, positively cannot do something, however, and you can be sure it will be done straightaway. Some will do it better than others, and several of the best 3-D works in the exhibition are satirical japes at the technique itself.

The cleverest: a 1991 Jim Shaw line drawing in red and blue, which shows an ex-con being killed in a drug deal gone wrong. Wearing 3-D glasses to get the comic stripâs volumetric effect, you read the text: âIn death, the world becomes 3 dimensional, the material world without time.â So much for the morbid glories of double vision.

The slyest: a 1905 pair of stereo-photographs by Joseph Jastrow, an experimental psychologist. They show a woman head on, her hands raised and pawing the empty space in front of her that corresponds with the surface plane of the photograph â behind which she appears to be trapped, like a fly in amber.

The boldest: Sigmar Polkeâs 2007 painting âThe Illusionist,â which assembles Victorian images of prestidigitation by assorted magicians, spiritualists and charlatans. Polke buried the picture, complete with paint drips, beneath a rippled surface of clear gel that mimics a lenticular lens â but actually accomplishes nothing. You move around to examine the big painting from every conceivable angle but fail to get any illusion of three dimensions at all. Only then do you begin to realize that youâve been puckishly had.

A few omissions from the show are surprising. A pioneering 1968 Bruce Nauman hologram is discussed in the fine catalog but isnât in the show â especially odd since LACMA owns it. Mike Kelley is also omitted, perhaps because his extensive use of lenticular lightboxes relates more to illusions of lifelike motion than of depth.

In Western art history, illusionism has been a continuous (and often contentious) issue since the Renaissance â and longer, if you skip over the ethereal Middle Ages and land in ancient Greece and Rome. Techniques by which artistic representations are made to resemble real objects in actual space can have profound meaning â or they can be trifling amusements, ways to pass time. Appropriately, âDouble Visionâ has both.

As our tempestuous digital epoch proceeds, however, what might come of 3-D for art remains to be seen. So far, the answer appears to be not so much.

⌠⌠⌠⌠⌠⌠⌠⌠⌠âŚ

â3D: Double Visionâ

Where: LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Through March 31; closed Wednesdays

Information: (310) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.