In 2012, four members of Mariachi Nueva GeneraciĂłn, decked out in their dapper charro ensembles, took the stage at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music as part of a performance organized for San Francisco Music Day. A video of the event shows the lights dimming to a warm red glow, after which the musicians raise their instruments and then ...

Silence.

Eventually, the trumpet player issues a short trill. Then, more silence. Some isolated notes emerge from the guitar. Silence. To watch the footage is to feel time expand, then contract. How long, exactly, have the mariachis been on stage? The crowd grows restive. Voices titter. âIs anyone in charge here?â yells a man. A woman exclaims loudly, âI hear music in my head. How âbout you?â

The performance was no accident. Itâs an interpretation of John Cageâs âVariations IIâ as reimagined by San Francisco-based artist and composer Guillermo Galindo. âJuan Jaula Cage Variations IIâ dispenses with Cageâs accustomed electronic instrumentation in favor of a trumpet, a guitar, a violin and a guitarrĂłn. Itâs a work that unites Galindoâs interest in avant-garde music with the Mexican folk traditions of his roots. (He was born in Mexico City.)

The enthralling 16-minute video of the performance appears in âSonic Terrains in Latinx Art,â a revelatory group show now in its final weeks at the Vincent Price Art Museum that explores the ways in which Latinx and Latin American artists have examined and engaged sound in their work.

Organized by curators Javier Arellano Vences, Pilar Tompkins Rivas and Joseph Daniel Valencia, the show features art and ephemera by a range of figures in the field. There are standard bearers such as experimental composer Pauline Oliveros and performance artist Raphael MontaĂąez Ortiz, known for dismembering pianos with an axe. (The museumâs first-floor gallery contains the splintery remnants of one â covered in feathers.)

Also included is a new generation of artists, including experimental Los Angeles vocalists Carmina Escobar and Dorian Wood; Tijuana rapper Muxxxe, a nonbinary performer known for their guerrilla performances at the U.S.-Mexico border crossing; and installation artists such as Jimena Sarno, Gary Garay and Marcus Kuiland-Nazario, who give sound a tactile dimension.

âSonic Terrainsâ is not an exhaustive survey, but it is ambitious, bringing together works by more than 30 artists throughout the United States â as well as a few from Latin America â and occupying all three floors of the museumâs galleries. Video and listening stations abound; one third-floor gallery is devoted to music videos.

The show is so dense that Times arts editor Paula MejĂa and culture columnist Carolina Miranda decided to tackle it together.

This conversation covers how silence can rile, the mariachi space opera staged by a bunch of Texas students and what a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer manages to make sound look like.

Miranda: I wanted to start with the piece by Galindo, which, very tellingly, opens the show. It felt to me as much a work of experimental music as it was a statement of physical presence: the mariachis standing onstage, looking impassive even as the audience grows impatient. Itâs a work that isnât simply about presenting Cageâs unusual score (a series of dots and lines spread out over 11 plastic sheets), but about resisting what the audience expects Mexican music â and, by extension, Mexican culture â to be.

The Los Angeles artist who outcools the skinny girls, Gabriela Ruiz delivers surreal DIY visions of herself in âFull of Tearsâ at the Vincent Price Art Museum.

I just wish the sound in VPAMâs installation was better because the audience reaction to what the mariachis are â and arenât â doing is as much a part of the piece as any music that gets played. Thankfully thereâs video as well as interviews with that eventâs organizers on Galindoâs website. Itâs really powerful.

MejĂa: Totally agreed. I couldnât hear much of anything in the video, but you can still feel the tension stewing within the audience. People jostle in their creaky seats, laughing uncomfortably when a musician plays a single guitarrĂłn strum. Itâs clear the audience is having a hard time processing the sight of four mariachis standing before them who arenât playing a song like âLa Bambaâ for their entertainment.

Another thing that makes this performance so avant-garde? Audience members arenât typically used to sitting with their own silence in a concert setting. Silence is discomfiting for a lot of people, so they start trying to fill that space with sound. And when they do itâs ... often revealing. The fact that they eventually started yelling out song requests for the mariachis to play is wild.

âJuan Jaula Cage Variations IIâ is wholly in the spirit of what John Cage initially set out to do with his piece: Back when he finished âVariations II,â in 1961, he stipulated that it was intended for âany number of players and any sound producing means.â So why not have a mariachi band?

Miranda: Since weâre on the subject of the avant-garde, I wanted to turn to the works in the exhibition by Raven Chacon, who this year was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music â and who, interestingly, once had a chance encounter with Cage as a kid.

Native American composer Raven Chaconâs âVoiceless Massâ for organ ensemble is the winner of the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for music.

Chacon, who is of Navajo and Chicano heritage, has a practice that encompasses an incredible breadth of work. In 2015, as part of the Postcommodity collective, he worked on a large-scale land installation, titled âRepellent Fence,â that bisected the U.S.-Mexico border with balloons painted with a scare-eye pattern. In 2020, he was one of two composers on the critically acclaimed experimental opera âSweet Land,â which was staged by the Industry here in Los Angeles. He also produces experimental sound pieces and compositions. I managed to lay my hands on the LP of his 2020 album, âAn Anthology of Chants Operations,â which contains a series of really subtle sonic elements â think: birdsong, chants, experimental instruments â all encased in an origami-like album sleeve.

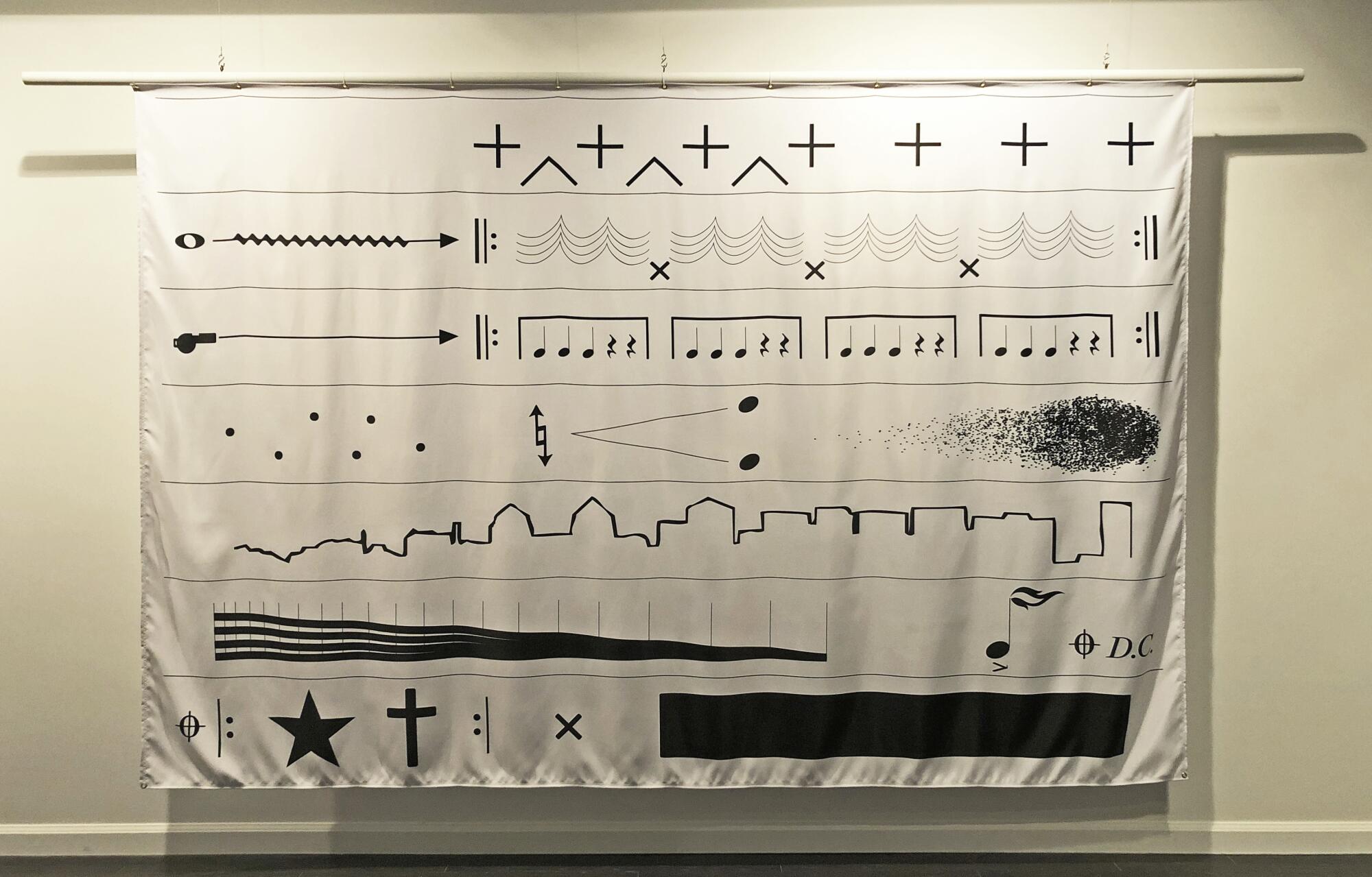

At VPAM, he has a pair of graphic scores on view, which includes the score for âMouth Piece (for a collection of objects),â from 2020, produced for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art â a composition for the sounds and pitches created by pre-Columbian instruments. (You can hear the work on an audio loop inside VPAMâs permanent collection gallery of ancient Indigenous art.)

I was really taken by the score for âAmerican Ledger No. 1,â 2018, on the first floor, which is inspired by the story of the foundation of the United States. Whatâs incredible about these graphic pieces is that you donât need to read a lick of music to understand what Chacon might be saying about our troubled history.

MejĂa: Iâm glad you brought up Chaconâs work, and especially this striking graphic score at VPAM. Itâs a moving piece, and I was in awe of its scale. It also made me wish I remembered something â anything â about reading sheet music from those piano lessons I took as a kid!

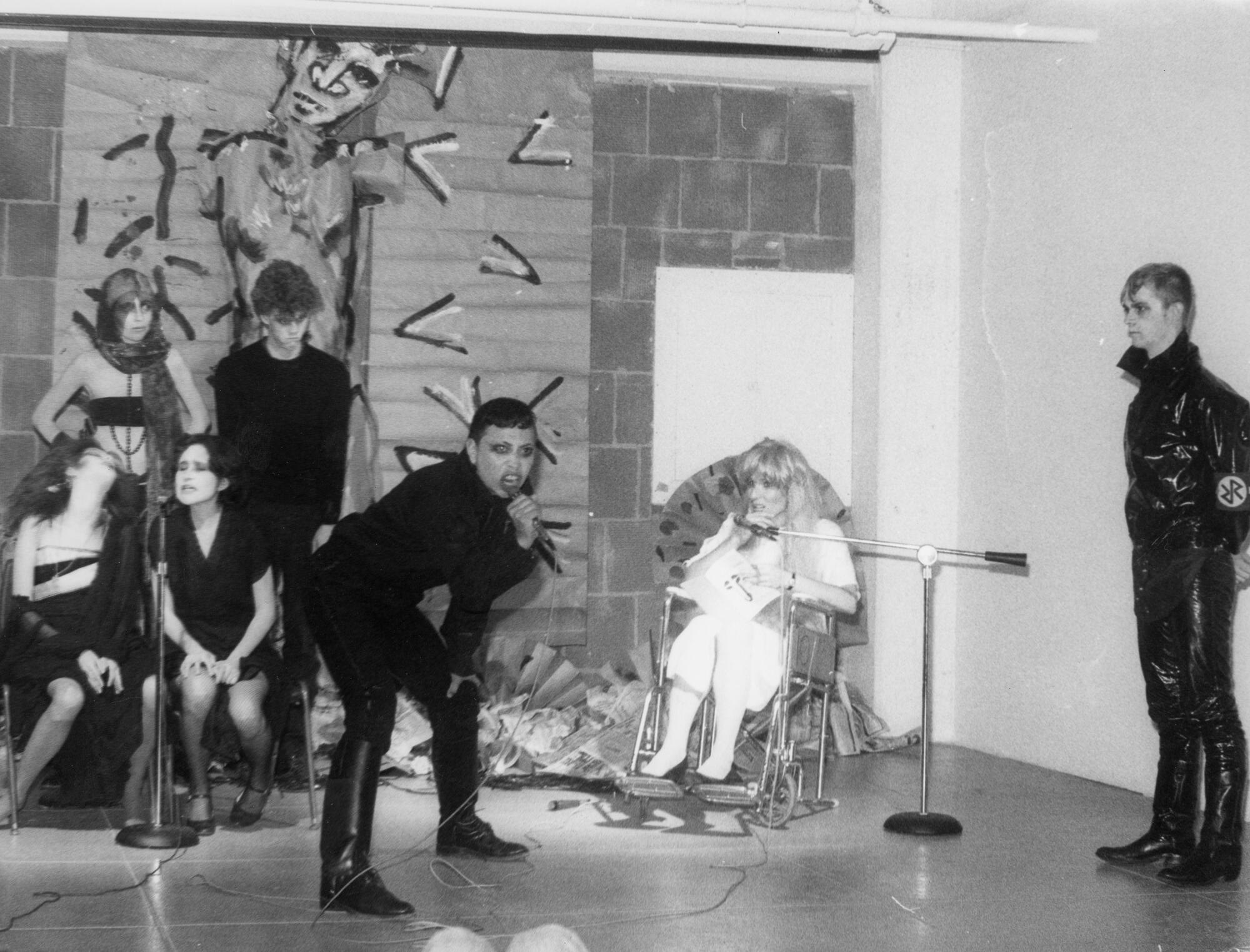

I also found myself drawn to Nervous Genderâs display. One of the museumâs galleries displays ephemera from the queer, electro-punk bandâs â80s heyday: zines, handmade fliers for the East L.A. bandâs performances and âMusic From Hellâ LP, a screen playing one of their high-wire performances. At a time when a lot of young people were picking up guitars following the shock factor of first-wave punk bands like the Sex Pistols, Nervous Gender was part of a trailblazing sect of the genre that used synthesizers to create melodies instead. They took a conceptual approach, intrigued by the way punk intersected with art and glam as a means of rebellion. The objects at VPAM give you a real sense of not only how central they were to the L.A. punk scene at the time, but also how provocative the bandâs shows were. I mean, one of their fliers features a cross deliberately drawn to look like a certain phallus...

On the subject of religion: This display got me thinking a lot about how punk rock musicians have at once rejected Catholicism and responded to it in fascinating ways over the years. Both Catholicism and punk rock have an element of spectacle to them. In Nervous Genderâs case, Gerardo VelĂĄzquez, the late founding member of the band, met and bonded with future bandmate Michael Ochoa in middle school because, as Ochoa put it in this short documentary about the band, the two shared a âfascination with all things âJesus Christ Superstar.ââ They had songs called âConfessionâ and âBeelzebub Youthâ that contended with religion, and one of their show fliers read: âLooking for a religious experience?â

Nervous Gender also went on to write a synth opera called âHomilyâ in 1981 â coincidentally not long after New York punk poet Jim Carroll (the author of âThe Basketball Diariesâ) wrestled with his faith in the searing album âCatholic Boy.â As someone who grew up Catholic and started bristling at it around the time I started getting into the Clash as a teenager, it struck a chord (sorry) with me.

The performance begins with coffee.

Miranda: I was intrigued by Nervous Gender too because Iâve regularly bumped into mentions of the band while writing stories about the L.A. arts scene of the â70s and â80s. In the ephemera presented at VPAM, you see so much cross-pollination with the cityâs visual arts and literary scenes â with figures such as Asco co-founder Harry Gamboa Jr. and poet Marisela Norte staging happenings with artists like RubĂŠn Funkahuatl Guevara, a performance artist and musician who also figures prominently in âSonic Terrains.â

For years, Iâve been hearing about Nervous Gender, so it was great to finally be able to see and hear a performance. Itâs not quite like being in some dank bar reeking of smoke and beer, but itâs as close as Iâm gonna get. Itâs also a reminder of how diverse and gender-bendy early L.A. punk was. Itâs something Iâve been thinking about a lot lately as Iâve listened to the Audible podcast âPunk in Translation,â about the Latino presence in punk. Itâs a presence that â surprise! â goes back to the termâs very roots.

MejĂa: Iâd also be remiss not to mention âMariachis on Mars,â the VPAM display by Sonic Insurgency Research Group, about the high school students of Crystal City, Texas, who put their own spin on a David Bowie rock opera in the late â70s to make a Chicano sci-fi epic play. The second-floor gallery display includes the productionâs program, a video of students warming up and rehearsing onstage and four colorful speakers, arranged on streamers, whirring with a cappella versions of âStarman,â among other Bowie tunes. Itâs incredibly gripping.

Hereâs how the play came together: Gregg Barrios, a high school teacher in Crystal City, had played Bowieâs âStation to Stationâ for his students, and it got them talking about how stylistically unusual the music was. Itâs important to note what was happening culturally and politically at the time: A few years before, a group of students in Crystal City â a rural community where 87% of high schoolers identified as Chicano or Mexican American â had led a successful walkout and strike for educational reforms such as hiring more Mexican American teachers, implementing bilingual education and more representation on the mostly white school board.

In the opera, the students probed the concept of âalienâ not only in the extraterrestrial sense but in the racist sense of being labeled as such in their hometown. Barrios wrote about this for Texas Observer when Bowie passed away: âWhen a cast member and his family were returning from a shopping trip in Piedras Negras, Mexico, some 35 miles from Crystal, a Border Patrol agent pulled them over for inspection. My student asked the officer why they were stopped. âWeâre looking for aliens,â he replied. To which our young actor retorted, âOh, I didnât know theyâd landed.â After that, we decided that our play might also explore how the Border Patrol perceived them â as aliens in their own land. A history teacher pointed out that during World War II, Crystal City had been the site of an âalien detention camp,â then located across the street from our high school.â

Iâm curious what you thought of the play and what other pieces stuck with you.

The artistâs work spotlights the land her ancestors inhabited and reframes what it means to be American in the museum galleries of the Huntington.

Miranda: That piece was poignant to me for all the reasons you mention. I was also impressed by the design of the installation itself: to listen to the different audio channels, you have to keep walking around that ebullient arrangement of candy-colored speakers, making listening an active, not a passive act. Itâs a far more compelling experience than being tethered to some monitor hung on a wall.

I was also completely bowled over by Mexican artist Luz MarĂa SĂĄnchezâs installation, âVis. [un]necessary force_1.01,â from 2014-2015. It consisted of a large white cabinet bearing almost two dozen 3-D printed objects resembling toy guns. But, really, theyâre speakers. Visitors to the museum are invited to pick them up, place them to their ear and play the individual recordings embedded in each: sounds of gunfire from shootouts between narcotraffickers that the artist harvests from YouTube. In other words, to listen to this work, you literally have to put a gun to your head.

The audio is absolutely chilling. One track begins as the celebration of a childâs birthday that devolves into what feels like an eternal shootout involving assault rifles.

The work is about narco-violence â but also the often-sensational ways in which it gets presented in the popular culture. A large wall text features the captions that appeared on the original YouTube videos, captions like: âLive shooting at a childrenâs birthday party in Mexico INCREDIBLE.â

This particular work is about Mexico. But in the context of our mass shooting epidemic here in the U.S., it could very well be about us. And it left me queasy.

It really articulated the cult of the gun. And it couldnât have made a better case for why sound can be so visceral as a medium. You can read endless stories about violence, but to hear the sound of a personâs voice as it is happening? That is something you will never forget.

"Sonic Terrains in Latinx Art"

Where: Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College, 1301 Cesar Chavez Ave., Monterey Park

When: Through July 30

Admission: Free

Info: vincentpriceartmuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.