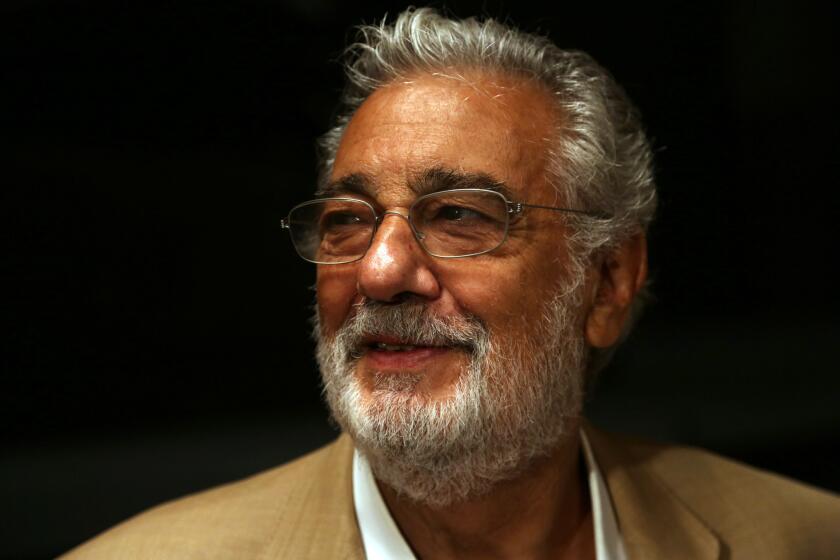

Commentary: What sexual harassment allegations against Placido Domingo could mean for opera culture

PlĂĄcido Domingo last appeared in Los Angeles in May, adding his 151st role as an opera singer, the âwildcat.â The titular fugitive in the zarzuela, âEl Gato MontĂŠsâ is fatally persistent in his love for a former girlfriend he returns to reclaim from her now-bullfighter fiancĂŠ after many years. This is a Spanish operetta Domingo had first appeared in 65 years earlier at 13 in his parentsâ Mexico City company as the bullfighter, making the two roles bookends to an illustrious career.

But with the Associated Press publishing accusations from eight singers and one dancer of Domingo being relentless in pursuing them with unwanted sexual advances, it all appears far too personal.

The outcome is far from certain. Domingo has denied the allegations as âinaccurate.â The accusers, but one, remain anonymous.

The ramifications are considerable. If proved true, the allegations would be a tragic ending to one of the great careers in the history of opera, a tenor and now baritone who has sung more roles than any other, as well as a conductor, opera administrator and celebrity. It would also be a sad revelation about the catalyst and voice of opera in Los Angeles.

Accusations of harassment against PlĂĄcido Domingo dating back to the 1980s raise many questions, and generate a statement of denial from the opera legend.

Reaction has, in this age of #MeToo and social-media immediacy, been quick and brutal. By Tuesday morning the Philadelphia Orchestra had dumped Domingo as the star of its season-opening gala next month. Not long afterward, San Francisco Opera followed suit by canceling Domingoâs Oct. 6 recital. New Yorkâs Metropolitan Opera said it would wait for the results from L.A. Operaâs investigation before making a decision as to whether Domingo will still sing in âMacbethâ at the end of next month.

On the other hand, the Salzburg Festival has said that Domingo will sing as scheduled in an upcoming concert performance of Verdiâs âLuisa Millerâ next week in Austria, conducted, incidentally, by L.A. Operaâs music director, James Conlon. L.A. Opera, itself, where some of the accusers claimed they were subjected to Domingoâs advances, has hired outside counsel to investigate the allegations.

There have been voices in L.A. for a while saying it is time, already, for the peripatetic Domingo to step down as general director. He is 78, and the company can seem his personal fiefdom. He conducts. He hires his wife to direct; her old and old-school production of âLa Traviataâ closed the season. Maybe the companyâs imaginatively daring and cosmopolitan president and chief executive, Christopher Koelsch, should run the whole show (itâs kind of hard to figure out who does what).

But Domingo is still an important and powerful presence, to say nothing of a tried-and-true draw. Biology be damned, he remains a compelling singer. He brings incomparable experience to the stage. He has performed with a broader range of great conductors and worked with a broader range of great directors than any musician alive.

Beyond that, he stands for something: opera for all. Born in Madrid, raised in Mexico City, he has been a proud model for a Latino community with too few superstars. His celebrity gets the attention of Hollywood. He opens the pockets of philanthropists. Iâve known him professionally for more than a quarter-century and am always won over by his charm and graciousness.

We also owe him big-time operatically in this town. His appearance with Londonâs Royal Opera at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival helped galvanize the Music Center to start L.A.âs first major opera company, further nurtured by Domingoâs advocacy. He became an advisor to the new company and two years later starred in its opening production of Verdiâs âOtello.â In 1998, he was named artistic director of the company before ultimately being named general director.

Before late Mondayâs news, L.A. Opera without the PlĂĄcido Domingo the city knows and loves was unthinkable. Iâm sure that thousands of Angeleno character witnesses can be found to speak for his kindness and generosity. No other singer has done more to help the career of young singers at L.A. Opera and elsewhere, thanks to his annual Operalia competition. The more common image of Domingo is not him pursuing women but of being pursued by them.

None of that, though, is evidence that the allegations of the women arenât true, that there arenât more sides to Domingo than the one generally seen. This is where we need context.

Part of Domingoâs defense has been what you might call the Joe Biden defense, that the culture has changed over Domingoâs 65-year career. It has, but that doesnât excuse improper behavior.

Whatâs also changed is our expectation that artists be unvarnished. Weâve come to think that we can divorce good art from bad behavior. Yet many of the greatest artists in history have been seriously flawed, and those flaws canât be separated from who they were or became.

In Domingoâs case, he took to the stage at a time when typical opera stagings were unremarkable theater with what seemed to us comic-book sets and costumes and when many singers stood and belted. Character had to come directly from the singer. For a tenor playing romantic leads, as Domingo did (he made a point of shying away from playing bad guys), charisma was as important an ingredient to stardom as his voice. And if you were going to pull it off on stage, a little life experience didnât hurt.

In addition, what worked onstage could embolden a singer offstage. Learn to be a Don Giovanni and maybe youâll want to try out a few of those moves yourself. Without a surfeit of confidence, Domingo, Pavarotti and any number of the greatest opera singers, male or female, probably wouldnât have reached the heights they did.

The question then becomes whether this a flaw of opera as an art form (and then we can talk about movies and theater and rock/rap music and fiction and portraiture) or is this what it takes to understand the human condition? If so, how far do we go?

I happen to be listening, as I write, to a broadcast from this summerâs Proms in London of a glorious performance of Tchaikovskyâs First Piano Concerto featuring Martha Argerich as soloist. This is one the most popular concertos ever written (and turned into a pop song as well), and Argerich is an incomparable pianist.

Well, Tchaikovsky happened to be a vile anti-Semite. And, Argerich happens to be an unrelenting defender of her ex-husband, the conductor Charles Dutoit, who has been accused of not only unwanted sexual advances but actual rape, which he denies. Argerich refuses to perform in the U.S. as long as Dutoit remains persona non grata here. He still gets gigs in Europe, Russia and Asia, where response to #MeToo charges generally is less reactive without a day in court. That is to say that norms are still not universal and may explain why Domingo remains welcome in Salzburg.

The outcome for Domingo will likely be an ongoing story for some time. As Biden, Brett Kavanaugh and the president of the United States have shown, accusations donât always end careers if popularity and support are strong enough, both of which Domingo also has. But artists are held to higher standards than politicians, which is also why we need to pay more attention to them and better understand them.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.