Review: A new book on rural America avoids the clichés. Why that’s only mostly a good thing

On the Shelf

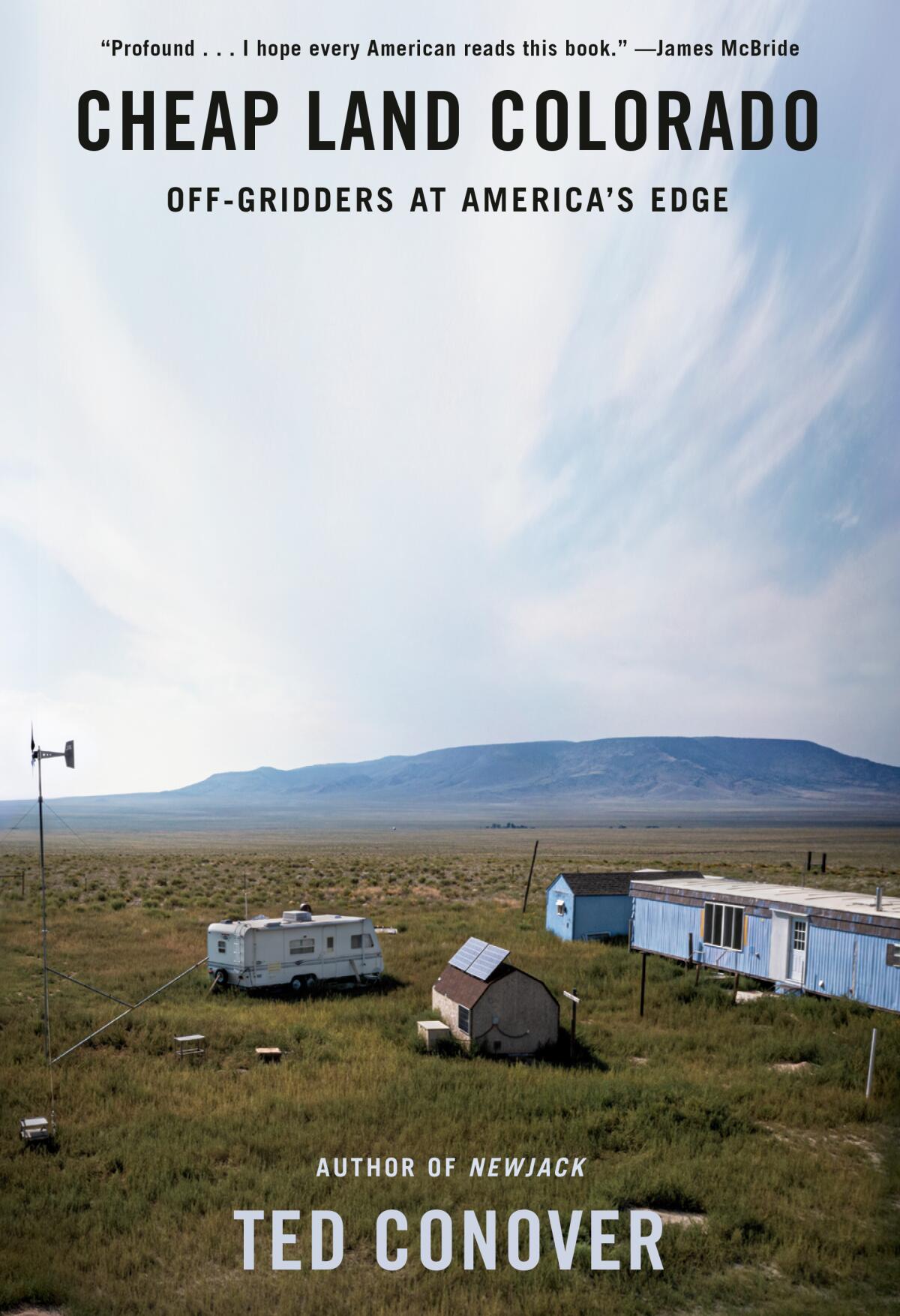

Cheap Land Colorado: Off-Gridders at America's Edge

Knopf: 304 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Once upon a time, American writers headed to the wilderness to commune with the oneness of things: Henry David Thoreau‚Äôs Walden Pond, Edward Abbey‚Äôs Arches National Park, Annie Dillard‚Äôs Tinker Creek. Now they go to the sticks to sort out our divisions. In ‚ÄúHeartland,‚ÄĚ Sarah Smarsh explored American poverty through the lens of her upbringing in rural Kansas. In ‚ÄúNomadland,‚ÄĚ Jessica Bruder showed how national parks and rural towns have become waystations for itinerant boomers cheated out of a comfortable retirement by the Great Recession.

Early in ‚ÄúCheap Land Colorado‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ all these books must have ‚Äúland‚ÄĚ in the title, by law ‚ÄĒ veteran journalist Ted Conover suggests he‚Äôll be delivering another book-length study of rural America as a symbol of a fractured nation. In 2017, Conover decided to move part-time to the San Luis Valley, a region near the Colorado-New Mexico border that‚Äôs long been a magnet for off-the-gridders and big-sky dreamers. The valley, he writes, offers one of the country‚Äôs last escape hatches, a way to be separate (but not a separatist). ‚ÄúA person could live in this vast, empty space like the pioneers did on the Great Plains, except you‚Äôd have a truck instead of a wagon and mule, and some solar panels, possibly even a weak cell-phone signal,‚ÄĚ he writes. ‚ÄúAnd legal weed.‚ÄĚ

Conover suggests that his stint will offer him ‚ÄĒ and us ‚ÄĒ a window into Trump-era America: ‚ÄúThe American firmament was shifting in ways I needed to understand, and these empty, forgotten places seemed an important part of that.‚ÄĚ His heart isn‚Äôt in the job, though. In many ways that‚Äôs a relief: Poor, weird, difficult, pretty, drug-sick and occasionally violent, the San Luis Valley is so far afield from urban or rural traditions that it‚Äôs not always identifiably American. Conover is wise not to boil his subjects down into types. But his reluctance also makes for a centerless, sometimes frustrating book that is uncertain about what kind of portrait of American life it means to present.

8 books you should read instead of ‚ÄúHillbilly Elegy.‚ÄĚ

Conover‚Äôs portal into this world is La Puente, an overstressed nonprofit that provides basic support ‚ÄĒ meals, firewood ‚ÄĒ to the region‚Äôs residents. Jobs are scarce and distant, and most people are living in weathered RVs; many, Conover observes, seem to be dodging warrants. In recent years, the county has been fining residents for failing to install septic systems, which generates more resentment than sewer lines. Without a chaperone, most of Conover‚Äôs conversations would‚Äôve been conducted across a rifle barrel, if they happened at all. (Though he doesn‚Äôt mention it, Lauren Boebert currently represents the region in Congress.)

Once he‚Äôs earned some of the locals‚Äô trust, though ‚ÄĒ a process that in some cases takes years ‚ÄĒ he finds a remarkable group of residents who are hard to stereotype. Troy, a one-legged former farmer. The Gruber family, a kind-hearted, home-schooling, weed-choked household whose bustle is punctuated by the foul-mouthed shrieks of a cockatoo named Sugar. Zahra, a Black woman in a largely white community, who‚Äôs escaped city life and a predatory ex.

Conover, for his part, genuinely loves the region, seduced by its surrounding mountains, its remoteness, its oddball inhabitants. But life there is hard in ways large and small. Overnight subzero temperatures freeze shut the doors of his RV. The Valley was a magnet for pill-mill pharmacies that exacerbated the opioid crisis. People arrived looking to make an investment ‚ÄĒ the book‚Äôs title comes from the Google search that brought one resident there ‚ÄĒ but there‚Äôs no profit to be made on land so remote and bereft of infrastructure.

In the 1870s the Valley was home to ‚ÄúColorado‚Äôs most famous cannibal‚ÄĚ (there‚Äôve been at least two), and violence persists there. An email Conover receives from a friend after he‚Äôs been there a while gently mocks his early idealism: ‚ÄúDo you feel free and safe on your land? Is that western sky still big and full of promise?‚ÄĚ

Conover writes that this book is a little different from the immersion journalism he‚Äôs best known for: He hitched rides on freight trains for his first book, 1984‚Äôs ‚ÄúRolling Nowhere,‚ÄĚ infiltrated Aspen‚Äôs elite for 1991‚Äôs ‚ÄúWhiteout‚ÄĚ and served as a Sing Sing corrections officer for 2000‚Äôs ‚ÄúNewjack.‚ÄĚ (He even wrote a book about his process, 2016‚Äôs ‚ÄúImmersion.‚ÄĚ) He‚Äôs a product of the New Journalism school of pure feature writing, which insists that the best message reporting can deliver is no message at all. (Even ‚ÄúCoyotes,‚ÄĚ his 1987 book on Mexican migrants heading to the United States, was too character-focused to move policy.)

In ‚ÄúThe Cold Millions,‚ÄĚ the novelist takes on proletarian lit, and honors his hometown, in the story of labor activists in early 20th century Spokane, Washington.

But even if Conover means to avoid rote big-picture conclusions about the San Luis Valley ‚ÄĒ if he‚Äôs content to share stories about trying to set up a wind turbine or working a volunteer shift at a shelter ‚ÄĒ an immersive portrait of the area has a hard time emerging. Excepting one early ride-along with a county officer, Conover dwells little on the region‚Äôs police and government, its crises or motivations for the septic-system crackdown. The area‚Äôs shaky economy seems to revolve largely around marijuana, but the details are unclear. Specificity might make for a more conventional, perhaps blander feat of reportage. But without that context, Conover‚Äôs observations can feel unfinished or overly romanticized. ‚ÄúIt was a beautiful, wild, and mysterious world, home to the semi-destitute,‚ÄĚ he writes. Part of the job of the immersion journalist is to remove the mystery.

That uncertainty about what to make of the San Luis Valley ‚ÄĒ is it beautiful or poverty-ridden, a haven for hippies or a sinkhole for survivalists, a potential remote-work utopia or climate-change dystopia? ‚ÄĒ may be what leads Conover to strain occasionally for deeper meaning despite his better instincts. In his conclusion, he writes, ‚ÄúSometimes I‚Äôve wondered if we can see in them an answer to the question, Who is America for, and who is it not?‚ÄĚ Call it the ‚ÄúHillbilly Elegy‚ÄĚ effect: Today‚Äôs nonfiction writer (not just of ‚Äúland‚ÄĚ books but bestsellers like Tara Westover‚Äôs ‚ÄúEducated‚ÄĚ) has to make some kind of assertion that rural America isn‚Äôt merely itself but a laboratory for how our society breaks and regresses.

Conover‚Äôs Colorado is too idiosyncratic for that. He talks to a few people who slot into the familiar tropes of rural red-staters ‚ÄĒ antivax, pro-gun, suspicious of coastal liberalism. Except the rules for living in the San Luis Valley don‚Äôt map to such simple binaries. That makes ‚ÄúCheap Land Colorado‚ÄĚ a fascinating portrait of individual residents. But as for a place that can teach us something about where America is going, that‚Äôs a different land entirely.

In August 1981, the summer of author Sarah Smarsh’s birth, my parents were broke. Again.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of ‚ÄúThe New Midwest.‚ÄĚ

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.