California Politics: The stateâs budget surplus is distracting

SACRAMENTO â No other activity of Californiaâs government stirs together public policy and raw politics in the heaping amounts used to craft the state budget.

A careful look at the spending planâs ingredients â outlined in January, haggled over through the winter and revised in May and June â offers a pretty good glimpse at the priorities of elected leaders. It also stands as a declaration, of sorts, about the role of government in the lives of Californians.

But from a historical perspective, the California budget process over the last few years has been out of kilter. And much of it comes down to one problem: The mountain of surplus tax revenue is a distraction.

By that, I mean that the glut of cash can obscure some of the larger, perhaps more important long-term trends in how taxpayer dollars are spent.

Letâs set aside the surplus

The surplus also spawns the kind of confusion that allows partisans, liberal and conservative alike, to use snapshots of the budget to their own political advantage.

Democrats can boast of solving all kinds of problems, often neglecting to mention these are short-term fixes. And Republicans decry out-of-control spending, not pointing out that much of it is one-time in nature.

The media arenât immune to the surplus distraction, either. Thereâs even been bickering among some in the state Capitol community about whether the word surplus is misleading because it wrongly implies that all of the unexpected cash is up for grabs.

In some ways, itâs not dissimilar from year after year of budget deficits in the early and mid-2000s â a crisis moment that planted the seeds of a government-canât-get-it-right narrative and resulted in its own set of weird (or maybe just misleading) explanations.

Itâs easy to see how it happens.

The numbers beyond the surplus

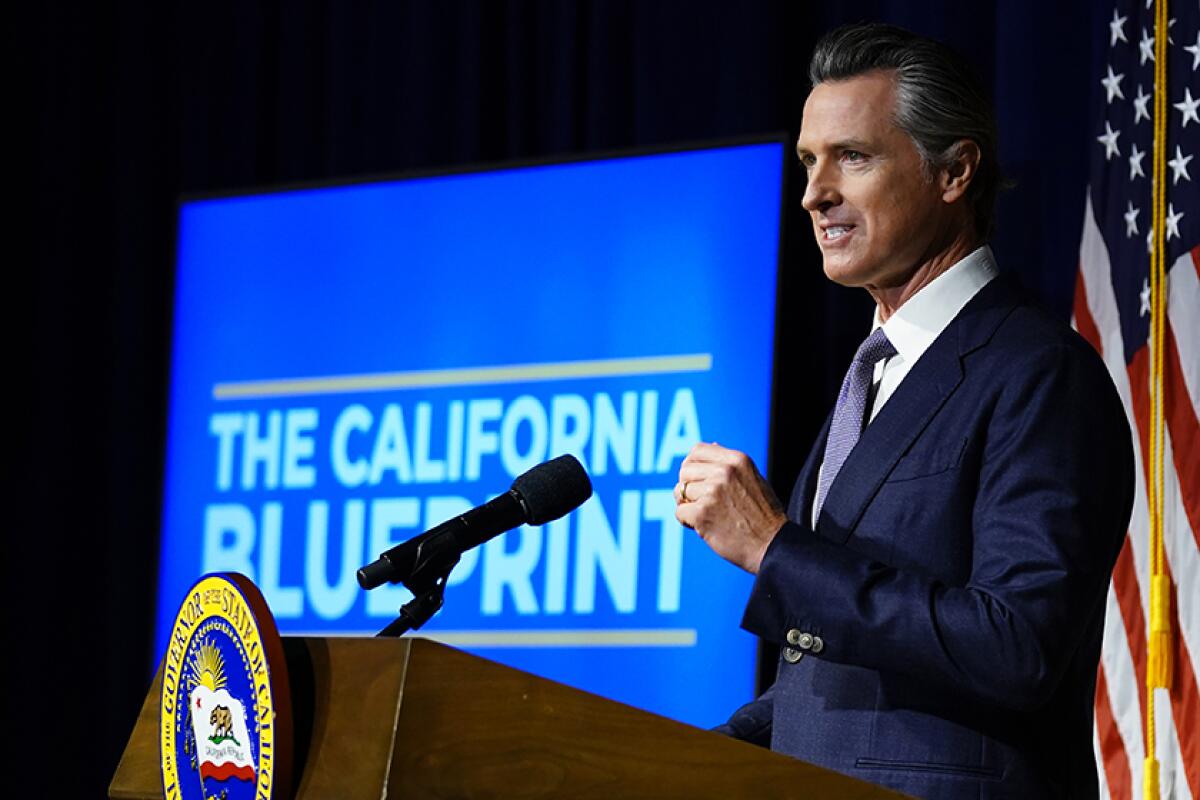

Take a cursory look at the basic summary charts in Gov. Gavin Newsomâs revised budget and it appears that state general fund spending rose between 2020-21 and 2021-22 by an astounding $85.7 billion â an increase of more than 50% in a single fiscal year.

Well, it did. But some context is in order.

A less publicized budget chart notes the current yearâs general fund spending includes $54.7 billion in one-time expenditures, items paid for with surplus cash. An additional $83.6 billion would be set aside for mandatory spending on public schools. Those expenditures, combined, account for about 56% of general fund spending in the fiscal year that ends June 30.

But they also donât reflect the kinds of spending decisions for which lawmakers are often criticized, the ones on programs that expand and grow over time.

The surplus and school dollars account for 46% of all general fund spending proposed by Newsom in the budget year that begins July 1. And in the budget year after that â which is only an idea at this point and not on the agenda of lawmakers â the governor proposes the surplus and schools, combined, would account for almost 44% of all general fund spending.

(And just to make it more confusing: the school spending totals are themselves larger than expected because they include a portion of surplus tax revenues that, by law, must be spent on education.)

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The inflation fight thatâs brewing

None of that is to say that the governor and Democratic lawmakers arenât raising long-term spending on what would be considered discretionary government programs, just not to the extent some might think when they read the headlines. Proposals in the latest budget plan would raise spending on higher education and healthcare services for low-income Californians, for example.

But Keely Martin Bosler, the governorâs budget director, said itâs important to note that future discretionary spending projections have been made with inflation pressures in mind. That âbuffer,â as she called it in a phone interview this week, runs in the billions of dollars in the latest budget proposal â a higher cost for basically the same services, something most Californians are feeling in their own budgets.

Boslerâs point was that the governor believes that inflation pressures arenât soon going away and the state shouldnât commit all of those dollars to expanding programs. Itâs an important topic to watch as final budget talks begin with legislators â given that some of them may believe itâs OK to shrink the inflation buffer in order to leave more money for helping more of the stateâs residents.

And then thereâs the spending limit

The long-term growth in some programs has been at the heart of a different discussion this year, one that centers on whether the California Constitutionâs spending limit might soon force cuts to vital programs.

Newsomâs latest budget proposal largely calls the spending limit a non-issue for the time being â a sharp change from his January plan, which predicted the state would breach the cap on appropriations. Now, the governor believes thereâs about $2 billion in breathing room, thanks to diverting billions in spending into categories that are excluded from calculating the cap.

Thatâs probably a short-lived victory. The independent Legislative Analystâs Office noted this week that the spending limit could force lawmakers next year to cut some $3.4 billion in spending, or divert it into excluded programs.

California politics lightning round

â Facing fierce opposition from Californiaâs powerful oil industry and trade unions, legislation to close down operations on three offshore oil rigs off the Orange County coast failed Thursday to win passage in a state Senate committee.

â Two bills inspired by the fatal accident on the set of the movie âRust,â both seeking industry changes, were also held in the Senate Appropriations Committee and wonât move forward in 2022.

â Newsomâs new budget provides few details on how he plans to fund a sweeping proposal to use the courts to order treatment for homeless individuals with severe mental illness and addiction.

â It will probably take persistence and a lot of political good fortune for Sacramento County Dist. Atty. Anne Marie Schubert to succeed in the race for California attorney general as an unaffiliated, independent candidate.

â Nor will it be easy for state Sen. Brian Dahle, a conservative legislator from Lassen County, in the race for governor as he faces an unfriendly political climate in a state where the GOP spent years slowly withering into irrelevance.

Stay in touch

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get California Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.