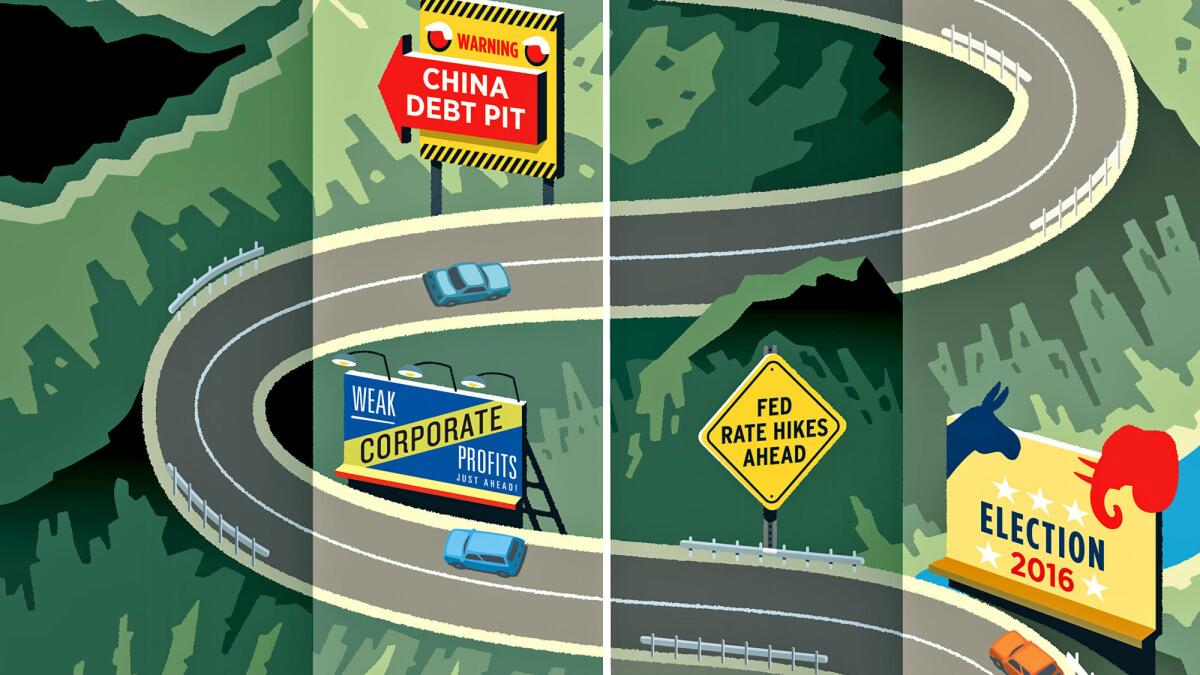

Protect your money: Look out for these uncertainties looming over the economy

The classic line about financial markets is that they can deal with good news and they can deal with bad news, but they just canât handle uncertainty.

By that reckoning, itâs a wonder markets arenât in full-blown cardiac arrest right now. Thereâs the bizarre drama and uncertainty of the presidential race, of course. But add to that a host of other unknowns that may have much more bearing on the economy and your finances than whoever wins the White House.

Consider: The Federal Reserve is poised to resume lifting interest rates from their post-financial-crisis depths. Thatâs a big risk for the high-flying stock market, particularly at a time when corporate earnings are on track to decline for a second straight year.

China is trying to avoid a new financial crisis of its own as bad bank loans mount. Japan has resorted to desperate moves to revive its long-moribund economy. And around the world, workers fed up with income inequality are demanding a bigger piece of the global wealth pie.

You canât know for sure how any of this will work out. But by understanding the potential outcomes, you can adjust your finances to fit your tolerance for turmoil.

Hereâs a road map to help navigate whatâs next in the economy and markets:

Be prepared for trouble with âsafeâ bonds.

One of the biggest negative surprises over the next 12 months may come from the investment that most people think is low risk: fixed-income securities. If market interest rates rise on new bonds, existing bonds paying lower fixed rates will slump in value.

Why would interest rates be headed up? First, because Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet L. Yellen and other Fed policymakers have indicated that continued strength in the U.S. economy would justify pushing rates higher â albeit slowly.

Their first increase since the 2008 financial crisis came last December, when the Fedâs key short-term rate was raised from near zero to a range of 0.25% to 0.50%. The central bank then went on hold. Now, Wall Street widely expects an increase this December to between 0.50% and 0.75%. And the Fedâs own official forecast sees two more quarter-point increases likely in 2017.

Thereâs another reason to believe that interest rates in general have bottomed after falling, in fits and starts, for the last 30 years: Voters in the U.S., Canada and Europe have demanded that governments attack the persistent problems of meager job growth and depressed incomes. That populist sentiment powered the presidential campaigns of both GOP nominee Donald Trump and Democratic challenger Bernie Sanders.

Government intervention would mean more fiscal spending and probably more borrowing via bonds to fund it. Greater borrowing doesnât necessarily drive interest rates up â but it can. And with government and corporate debt already at extreme levels, more debt hitting the market could give bond investors indigestion.

Both Trump and Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton have promised to ramp up infrastructure spending.

Tellingly, âneither candidate has talked about reducing debt,â said Andrew Pease, global head of investment strategy for Seattle-based Russell Investments, which manages $244 billion for clients.

European Central Bank President Mario Draghi is encouraging European governments to think stimulus as well. Although the central bank is holding interest rates at rock bottom, that is ânot enough for delivering real and sustainable growth in the long term,â he told the European Parliament last month. Governments also need to step up, he said.

Rising populist sentiment shows âweâve reached a point of intolerance,â said Chris Brightman, chief investment officer at money manager Research Affiliates in Newport Beach. Congress could seek to block the next presidentâs efforts, but âpeople are going to demand policies that reverse the trendâ of wealth inequality, Brightman said.

Whether investors believe that shift will happen isnât yet clear. But there has been a mood change in global bond markets in recent months. Government bond yields have rebounded from summer lows. The U.S. 10-year Treasury note yield has risen from a record low 1.32% in July to 1.80% now.

Jeffrey Gundlach, bond guru at DoubleLine Capital in Los Angeles, has been telling clients since July that he believes interest rates have finally bottomed worldwide, and that the 10-year Treasury yield could top 2% by year end.

So far, bond owners may barely notice that the value of their securities has declined. And there have been plenty of times over the last three decades when interest rates have temporarily rebounded, only to fall again. Unless inflation rises, rates could stay relatively low for years.

But this is a good time for bond investors to understand exactly what kind of risks they face if interest rates have indeed bottomed.

U.S. stocks could face wild volatility from a maelstrom of crosscurrents.

After last winterâs brief swoon, stocks had mostly been in steady uptrend. The Dow Jones industrial average hit a record 18,668 in August, and has slipped 2.8% since, to 18,138 Friday.

Now the rally faces major tests. For one, the presidential election outcome could quickly accelerate or reverse stock bets that have been made on the race in recent months.

Some investors have dumped biotech shares, for example, on fears that Clinton would try to severely restrict pricing of new drugs. Meanwhile, Trumpâs promise to build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico has helped boost some infrastructure stocks, including Mexican cement giant Cemex, which has extensive U.S. operations. The stock has more than doubled from its January lows.

Soon after the election, Wall Street will pivot back to focusing on the Fed, which will meet Dec. 13 and 14 to vote on a rate increase.

Between now and then, American companies will announce third-quarter earnings and give guidance on the near-term outlook. Those reports will be crucial because investors are counting on a significant improvement in recent profits to set the scene for an even bigger rebound in 2017.

After peaking in 2014, total operating earnings of the blue chip Standard & Poorâs 500 companies began to decline in 2015 and have continued to fall this year. But third-quarter profit is expected to be down just 0.4% from a year earlier, according to analyst estimates tracked by Thomson Reuters IBES. That would be a sharp improvement from the 5% drop of the first quarter.

Whatâs more, analysts expect earnings to start growing again in the fourth quarter â and then surge 14% in 2017 as a whole.

Through summer, U.S. stocks overall continued to hit new highs in part on profit optimism. If earnings expectations dim, so does the bullish case â because investors may lose hope that profit growth will resume anytime soon.

The S&P 500 index, at 2,132 on Friday, is priced at 18.2 times estimated 2016 operating earnings. Wall Street canât agree whether that is expensive or reasonable. But no one would argue itâs cheap.

Super low interest rates have helped to justify high stock price-to-earnings ratios. If rates rise, that could pull down P-Es.

If you canât stand the risk of more market volatility ahead, raising some cash makes sense. But true long-term investors may not see enough reason to get ruffled yet.

There may even be an ironic silver lining in the corporate earnings cloud. Part of the reason profits are under pressure is that U.S. workersâ wages finally are accelerating. Average hourly earnings grew 2.6% year-over-year in September, the government said. The pace has steadily picked up from 2% in late 2014.

The increase isnât gangbusters. But itâs moving in the right direction, raising hopes for the so-called virtuous circle: As Americansâ incomes rise so does their spending power, in turn driving up many companiesâ sales and earnings.

âI think weâre seeing the turning pointâ in wages, Pease said.

That could favor companies that cater to workers in lower- to middle-income brackets as opposed to chasing after high-end consumers, said Brad McMillan, chief investment officer for Commonwealth Financial Network in Boston, the nationâs largest privately held independent broker group.

In other words, think about stocks like Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Target Corp. as potential beneficiaries, he said.

Many foreign stock markets may have the most to gain in the next year or so â if the global economy holds up.

Thatâs because theyâve lagged behind the U.S. for so long.

There has been no place like home for American investors over the last five years. The average U.S. blue-chip stock mutual fund has gained 12.9% a year in that period, according to Morningstar Inc.

By contrast, the average European stock fund rose 6.3% a year. Emerging markets funds gained a mere 2% a year.

But the picture began to change this year with a rebound in emerging markets, including Brazil, South Korea and India. Political and economic turmoil in many developing markets had sent investors fleeing since 2010. The rising U.S. dollar further devalued foreign securities.

By early this year pessimism bottomed, and bargain hunters poured in. Year to date, the average emerging markets stock fund is up 12.9%, compared with 4.4% for the average U.S. blue-chip fund.

Richard Turnill, global chief investment officer for money management giant BlackRock Inc. in London, said emerging markets overall are âstill the area that looks the most attractiveâ longer term. Local interest rates are relatively high in many developing countries. But as money flows back to them, it should help push rates lower, boosting economic growth, Turnill said.

China, however, remains the biggest wild card. The government is trying to manage a soft landing for the economy even as export growth weakens, and the Chinese banking system is swamped by bad loans.

Europe, too, still is dealing with a banking crisis because it failed to fully solve the bad-loan problem spawned by the financial crisis. âThe banks are a very big headwind for European equity markets,â Turnill said.

But Russell Investmentsâ Pease thinks European stocks could outperform U.S. stocks over the next five years, given that U.S. shares now are much more highly valued. âAnd if we do get a shift to fiscal [stimulus], Europe would be a good beneficiary of that,â he said.

Finally, an overarching caveat: If you believe that whoever wins the White House joins with Congress to throw out trade agreements and favor economic isolationism, itâs fair to say that all market bets would be off.

What ails the U.S. economy wonât be solved âby trying to bring back jobs that donât exist anymore,â said Roger Aliaga-Diaz, a senior economist at mutual fund titan Vanguard Group.

ALSO

8 ways to avoid ruining your financial life

Tiny homes are all the rage. But hereâs why the market is more bust than boom

Aliso Canyon leak made people feel sick for months; in this Alabama town, itâs been eight years

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.