Bikers bring new life to a Mojave Desert ghost town

The old mining town of Randsburg roars to life on weekends with off-road enthusiasts — often entire families — drawn by former motorcycle racer Goat Breker.

In 1899, this gold-rich Mojave Desert town had a population of 3,500 and boasted churches, bordellos, saloons, hotels, a thousand-seat opera house and a skating rink.

But when the mines played out, the miners moved on â and left behind boarded-up squatters' cabins, open shafts and the rusting hulks of mining equipment, preserved for posterity in the dry desert air.

Along Randsburg's sun-baked main street, vintage storefronts â a barber shop, a store advertising pickles and relishes, a shop that vulcanizes tires â fade to gray like an abandoned Western movie set.

A sign in front of the fire station says, "In case of fire, be calm. Yell loud." Another, in front of a shuttered antique store, says, "Hopen For Business."

On a Friday afternoon, the traffic consists of a couple of quails, a jack rabbit, maybe a desert tortoise or a tumbleweed.

By midday Saturday, though, the town is swarming. Hundreds of dirt bikers roar into town, dressed in body armor, heavy boots and helmets, their bikes' knobby tires raising clouds of silty dust behind them.

They aren't in town for a motorcycle race, or a movie shoot, or a rumble. They're not looking for trouble. They've come for a bowl of chili at the White House Saloon, a shot of bourbon at The Joint or a banana split at the Randsburg General Store's 100-year-old soda fountain.

"Help the economy? They are the economy," says Jim Veach, who owns the White House Saloon. "Without them, I'd be out of business."

Saturday midnight finds professional motorcycle rider turned unlikely hotelier Goat Breker standing around a fire pit, watching his guests drink and listening to tall tales about their motorcycle exploits.

Sunday morning finds the 54-year-old standing over a griddle, frying bacon and eggs for their breakfast and helping them work through their hangovers.

Rangy and burnt by years in the sun, the shy, gravel-voiced Breker doesn't smoke or drink, chastened by spending his childhood watching his father and two older brothers battle with booze and drugs â the brothers who took away his birth name of Todd and named him Goat.

Motorcycles saved him: "That's what kept me off drugs and alcohol," he says. "I saw what it did to my brothers. I knew I had it in me, too."

Before he bought the former Cottage Hotel at the high end of Randsburg's main drag and turned it into Goat's Sky Ranch, he'd been a pilot, a fireman, a boxer, a juggler, a professional drummer. He had multiple motocross championships under his belt â and quit when he'd had enough.

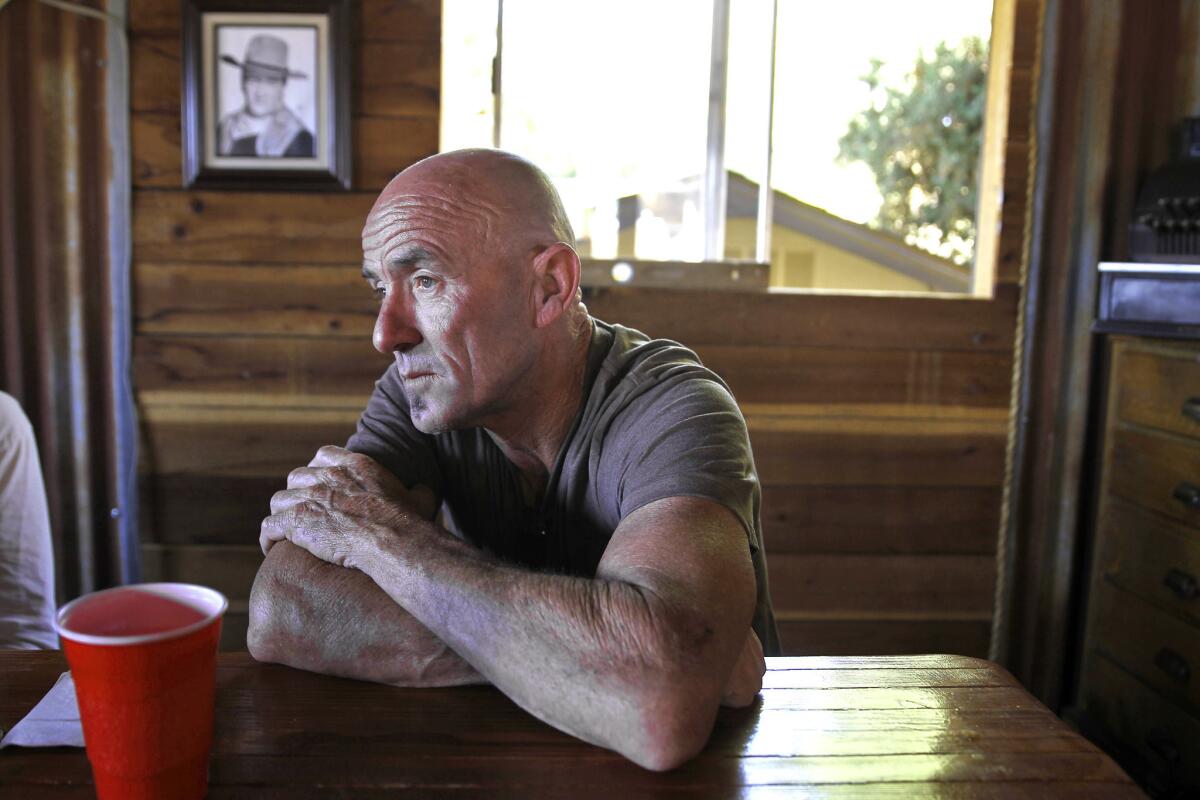

Goat Breker, a former motocross champion-turned hotelier and desert off-road guide, takes a lunch break at his Sky Ranch after a morning of off-roading near Randsburg. More photos

"I broke my hip. I broke my neck. I had a couple of surgeries," he recalls. "I was lucky I never had anything serious happen to me."

Out of racing, he worked as an instructor at a school for the deaf, owned and managed the famed Perris Raceway motocross track and had his own custom sunglass company.

One day his father said to him: "You can afford to retire. Are you going to wait until you have cancer?"

So, in 2005, Breker closed down the sunglass business, liquidated his holdings and moved to Randsburg.

He knew the town from the 1960s, when his father used to race desert events out of nearby Trona. Since then, he'd visited Randsburg to see an old friend, veteran motorcycle elder Jim Cooke, who like Goat's father had raced motocross and desert in the 1960s and 1970s.

Breker was already known in the Mojave Desert for his racing past.

Dave McGachan, who owns a shop in town called Motohelp, calls him "a legend." Pam Keiser, who owns the General Store, says, "Goat is a celebrity â one of the greatest of all time."

When Goat learned that the house next door to Cooke's was for sale, he bought it, fixed it up and brought his dad to live with him. Then he bought another cabin for his friends. When the Cottage Hotel came onto the market in 2009, Breker made an offer.

"I bought it for a girl, for her to have something to do," he says. "Turns out she didn't want anything to do. So she's gone, and I'm still here."

Breker insists he wasn't catering to bikers when he bought the hotel and expanded it â doing the plumbing and carpentry himself â then bought and restored several more cabins.

"I didn't know this was going to be for motorcycles," he says.

But the renaissance of Randsburg has paralleled a boom period for the off-road business. The motorcycle industry, which bottomed out with the 2008 recession, has shown signs of new life. The dirt bike business has remained relatively healthy, and motor sports companies are putting new vehicles onto the market â especially four-wheeled, two- or four-person recreational off-road vehicles, or ROVs, that make it possible for whole families to go off-roading.

During the cool months of the year â the period from Memorial Day to Labor Day is so hot that Randsburg is a ghost town even on weekends â the hotel is full, booked by visitors who pay $85 for a simple, rustic room, or $125 to $185 for a furnished cabin.

Managing the Sky Ranch with Breker is Scrappy â full name Linda Argyris â a youthful mother of five and grandmother of two whose family, she says, came to the Mojave Desert in 1822, then discovered gold and helped build the town that became Randsburg.

Scrappy, a tall, dark-eyed woman who wears her dark hair in a long braid, describes her relationship with Breker as "best friends," and says, "We don't believe in marriage."

Like the rest of Randsburg, Breker depends almost exclusively on the off-road trade.

Ryan Abbatoye, a guide with Chris Haines Motorcycle Adventure Co., leads Goat Breker's group of off-roaders through the Mojave Desert area where gold was discovered in the late 1890s near Randsburg. More photos

On weekends he and a partner, the legendary off-roader and adventure guide Chris Haines, run group tours, leading packs of enthusiasts on motorcycles and Arctic Cat ROVs on two-day open desert runs to Las Vegas. During the week, they train military personnel in how to use off-road vehicles to launch assaults in the deep sand, using night goggles to navigate the narrow canyons carved into the surrounding desert.

Some of the townsfolk have mixed feelings about Breker and his booming business. They complain that his guests go on his tours, and eat and sleep at his bed and breakfast, but don't patronize the town's businesses.

"He's pretty isolated," one says, asking that he and his business not be named. "His guests never leave Sky Ranch."

But few dispute that there's new life in this tired old town.

On an average weekend, the Randsburg population can swell from 69 to more than 2,000 â and double that on Easter or Thanksgiving weekend â as the bikers ride in from campsites at Jawbone Canyon or California City.

Heâs done nothing but good for this place.ââ Business owner on Goat Breker's effect on Randsburg

Some of the riders, mostly men, are accompanied by wives and families driving ATVs, ROVs, dune buggies or Jeeps. The visitors poke around the town's dozen antique stores, pose for pictures in front of the two century-old churches, or pretend to lock themselves up in the old city jail.

"People who haven't been here in a while ask me what happened," says Motohelp owner McGachan. "I tell them, 'It's all Goat. He cleaned this place up.'"

"Nobody had built a house here for 20 years before he came to Randsburg," says Charley Salwasser, the grizzled former prospector who runs Charley's Ore House, an antique store filled with memorabilia and rusty mining tools. "He's done nothing but good for this place."

Breker, for all his love of motorcycles, doesn't ride them anymore. He conducts his desert tours from the seat of a battered four-wheel drive truck that sits in front of the hotel, day or night, with the keys in the ignition.

Bill Tassio, right, spends time with his 6-year-old daughter, Lyla, while camping with family and friends in the desert near Randsburg. More photos

He says riding made it impossible for him to have a family â "I can't have kids," he says. "Too much motorcycles."

But he is passionate about making Randsburg a playground for young people.

"I just want city kids and their families to come out to the desert, to sit by a campfire and see the stars," Breker says.

At that moment, two men on dirt bikes putt-putt respectfully up Randsburg's main drag, followed by a gaggle of children on smaller motorcycles and several more adults in a four-wheeled ROV.

"See that?" Breker says brightly. "That's what I'm talking about. Families! That's all I want to get out of this whole experience."

Follow Charles Fleming(@misterfleming) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Snow polo a high-end diversion for China's rich

We have a class called Introduction to Noble or Expensive Sports.â

A mosaic-loving family's journey of many tiles

I love that in Los Angeles everyone can express themselves.â

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.